Its grip is firm, yet soft. It confines you, but with the best of intentions. Like a weirdly sexual caterpillar or a slug that has come to rest on your shoulders, it covers the back of your head and your neck, and its ends stop just short of your chin. You might feel a cool microfiber surface stroking the skin of your cheek. You can pull at it and squeeze it, knowing that it will always dutifully return to its plump horseshoe shape.

The neck pillow is available in virtually every airport shop and enjoys omnipresence around the necks of frequent and casual travelers. It has come to signify the very mode of being on the move. In the following, I want to think of the neck pillow in terms of the space it both signifies and creates–which I think is a kind of blurred space, one in which the transition from public to private, from comfort to control becomes seamless according to a neoliberal logic.

Let’s start by looking at how this relates to the experience of the airport and of traveling itself. At the airport, we often find ourselves stranded in places that are designed for waiting, for passing time, or rather, for waiting for time to pass. We share boarding areas, waiting halls, transit lounges, and rows of metal chairs in the terminal with other travelers. We do so for unexpectedly long periods of time, in which case it is very likely that at one point we will make ourselves at home. We brush our teeth and change our clothes in the public bathrooms, take a nap on our luggage, or sit on the floor next to the nearest outlet to charge our phones. In the airplane itself we are seated side by side with strangers, getting closer with our seatmates while we eat, stumbling over their feet on the way to the bathroom. We make small talk and fall asleep next to each other.

The waiting hall is certainly not the only place where a form of isolated togetherness can emerge, just as the experience of being physically close in a sometimes awkwardly discreet manner is not singular to the airplane cabin. Rather, these are permanent modes of public life. According to Rem Koolhaas, we live in “infrastructures of seamlessness” (175), a “fuzzy empire of blur [that] fuses high and low, public and private…to offer a seamless patchwork of the permanently disjointed.” This is what Koolhaas calls Junkspace–and it is not only the material result, but also the immaterial sum of modernization. We do not inhabit it just as it inhabits us. The airport is not only part of this clutter, it is itself Junkspace, “always interior, so extensive that you rarely perceive limits.” And everywhere “there are seating arrangements…as if the experience Junkspace offers its consumers is significantly more exhausting than any previous spatial sensation.”

Traveling and constantly moving around are not exceptions anymore. At least in the world of Western neoliberal capitalism–where productivity, mobility, and flexibility are valued above everything else, where we dream of the ideal of the pure flow, where mindfulness and relaxation are preached under the pretext of precisely that logic–the notion of traveling has shifted from being a singular event to becoming a continuous mode, one that is deeply entrenched in our personal and professional lives. And yes, we’re getting lost, and yes, it’s exhausting. But it’s an exhaustion that we’ve learned to celebrate and fetishize. After all, who doesn’t secretly enjoy talking about their tense necks?

Connecting the head with the torso, the neck is our bodily transit zone, a physical in-between. Anatomically it includes the cervical spine and its connection to the back of the head, the neck muscles, and receptors of surface and depth sensitivity. These complex anatomical structures make the neck prone to a whole range of disorders and conditions. Trending at the moment: the so-called “text neck,” which describes repeated stress injury and pain in the neck resulting from excessive screen watching or texting on handheld devices.

In the back of our necks, we are vulnerable. In many German idioms, we find something proverbially sitting in the back of our necks, the enemy, fear, or a demon that prompts us to cause mischief. Der Feind, die Angst, der Schalk sitzt im Nacken. Having a millstone around one’s neck, a saying derived from the New Testament, describes a burden or responsibility we can’t rid ourselves of. Having someone breathe down one’s neck figuratively describes the feeling of being monitored, of someone coming too close to you. Bowing the head and bending the neck is a gesture of both humility and surrender. Namaste or mortal blow. The neck is sensitive. It needs support.

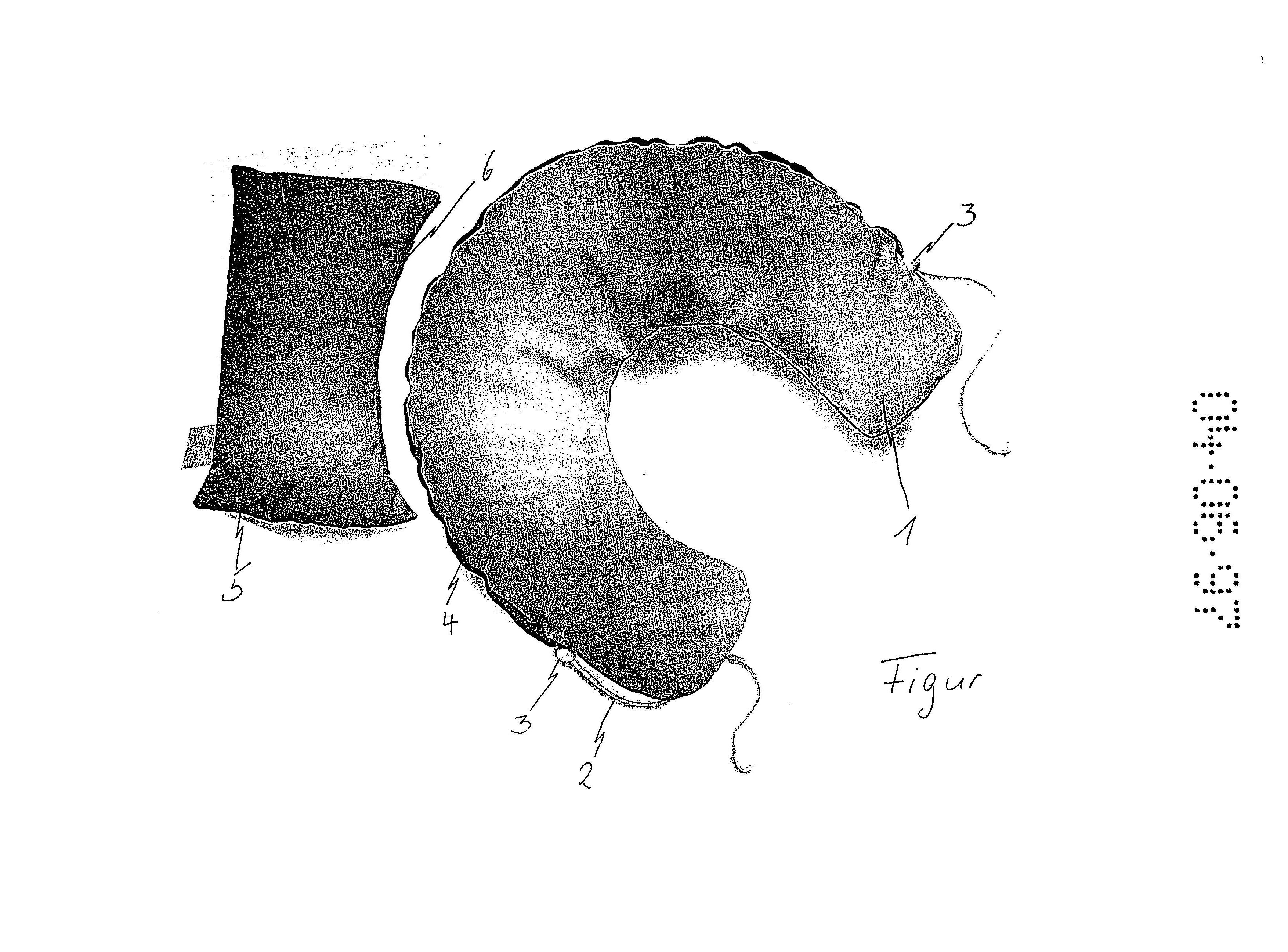

Figure 1. Tilia GmbH, “Gebrauchsmodell Nackenkissen.”

The idea of the pillow as a support for the head while sleeping is age-old. Its history (at least among humans) dates back to 7000 BC in Mesopotamia, where stone pillows would elevate the head of the wealthier citizens to prevent insects from crawling into their mouths and nostrils. Naturally, it wasn’t until the industrial revolution that the pillow became an affordable mass product. Since then, the pillows have been piling up, our lives becoming padded.

The neck pillow–in its simplest croissant-like shape–has been around for roughly forty years. In 1997, Tilia GmbH, a German manufacturer and distributor of orthopedic products, patented the “Nackenkissen” as a utility model. Then, this neck pillow was state of the art; with its moisture absorbing cotton and odorless polystyrene pearl filling, it was an update to its predecessor, the rubbery inflatable pillow. Since then, this still quite basic, let’s say humble neck pillow, has received various upgrades. When looking for a Nackenkissen in October 2018 on German Amazon, we are offered a choice of more than two thousand products. My favorites: an ergonomically shaped pillow which you can wrap around your neck like a snake for additional chin support; a pillow with an attached hood for a feeling of privacy and extra coziness; a very unsettling pillow in the shape of two hands—the promotional slogan advertises a “sleep surrounded by hands.”

What we learn from this short excursion into the contemporary neck pillow market is that while there are of course still the simple, cheap, and mass-produced pillows, objects mindlessly left behind at airports and in planes, there are also those that clearly connote a certain status and (life)style as well as those that cater to ever more specific niche markets. What struck me the most, however, was the way in which the neck pillow is growing in size to cover larger areas of the neck, the head, sometimes even the upper body, or the whole head. The neck pillow physically and symbolically grows on us; its value now far exceeds its intended practical function, namely to be, quite literally, a pillow for the neck.

Figure 2. “Travel pillow MonPère.”

On my most recent transatlantic flight I saw quite a few passengers who confidently wore their pillows around their necks even prior to boarding the plane, like a fashion accessory. Maybe this was a matter of pragmatism. After all, a frequently asked question in online travel forums is: does a neck pillow count as carry-on luggage? But the image of an adult man wearing a baby blue cotton neck pillow laced around his chin made me wonder: what do we actually want from this object? Regardless of whether a neck pillow actually keeps it promises, it seems that these promises themselves and what they evoke—often paradoxical notions of rest, comfort, support, and sensitivity—are what makes them so appealing to so many.

The neck pillow lets us rest. Mobility is both a premise for and the inevitability of taking part in global traffic. We need to keep moving. When reading the product descriptions of virtually any travel neck pillow, the phrase arrive rested recurs not so much as a promise, but rather as an imperative. Don’t stop to rest. Keep moving. The neck pillow promises to provide comfort when we find ourselves in potentially uncomfortable situations. Situations in which we need to keep our composure. The neck pillow will save us from a range of possible hazards of traveling, like public embarrassment by snoring. It will catch your head when it inevitably tilts to the side, or, even worse, onto the shoulder of your neighbor. It will soak up the drool that might escape the corners of your mouth. Comfort here also means: I need my (private) space. Please keep your distance. A neck pillow lets us imagine privacy, or even domesticity, in a space that is neither public nor private in the first place but rather embodies a complex interrelation of both.

The neck pillow quietly sums up the paradoxes of our neoliberal present. When wearing it, we are proudly displaying our exhaustion for everyone to see. We are settling in the in-between, a space in which the craving for comfort is control, in which the need for privacy comes with the inevitability of the public sphere.

Cover image: Jon Rafman / Dream Journal 2016-2017 / Single Channel Video / Music by Oneohtrix Point Never and James Ferraro / Dimensions variable / 49:17 mins / Copyright Jon Rafman / Courtesy the artist and Sprüth Magers