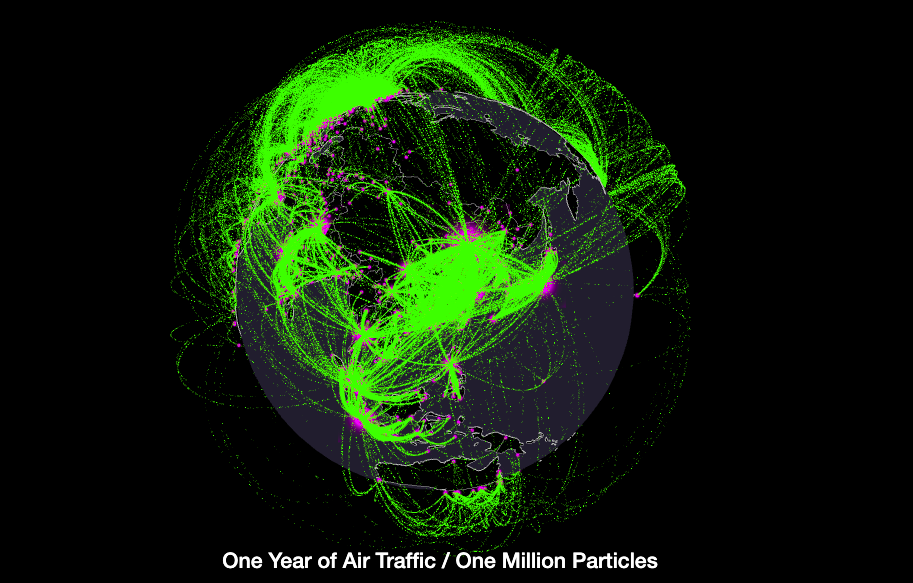

This animated map made by Max Galka shows passenger air traffic over a year. Every small dot stands for around two thousand people. We are all probably familiar with these visualizations showing the marvel of global mobility at scale. I would like to propose a counter-mapping. I focus on the airport as a process of bordering and make use of other scales of data and statistics (mostly about migration in Germany) that are usually not shown or that stay hidden in such animated maps.

In visualizations of air traffic, connections between destinations promise us the possibility of flying the world. See for instance connections from Frankfurt airport for Sky Team, or direct and connecting flights from Frankfurt.

The airport has been seen as a non-lieu (non-place) (Marc Augé), a place of transit, where fluxes are enabled and fostered. But before entering this space, says Augé, there is a need to prove our own individual identity. As Lisa Parks argues, the airport “is much more than a non-place, it has become a vital place where security, technology and capital collide.”

Following Parks, I would go further and question the promised global mobility of airports. I ask which fluxes are instead disabled. What if motions are rejected? What if movement is deviated? An airport is, as I’m about to claim, a place where a continuous process of bordering takes place.

Did you know that before July 2012 there were direct flights from Frankfurt to Syria? After the start of the Syrian civil war, Europe imposed sanctions on Air Syria and all connections to Syria were cut off. If before 2012 we could fly from Aleppo or Damascus in four hours, today there is no way to take a direct flight.

The story of Nazir Wakil, a forty-year-old optometrist, shows how long the journey to Syria might last even when flying. His trip can be tracked via this animation made by the Financial Times. In Turkey he paid human smugglers around €13,000 to travel by plane to Istanbul and from there to the Maldives with his own Syrian passport. Finally, with a fake Italian passport he traveled to Frankfurt airport and through controls. His travel from Syria to Frankfurt took approximately one month. Not only did his journey last longer, it was illegal, very expensive, and implied a spatial diversion. Most interestingly, the highly educated doctor Nazir Wakil was privileged if you compare his journey to the journeys of many other exiled Syrians. It is in fact possible to claim asylum directly on arrival at the airport. The “procedure in case of entry by air,” according to Asylum in Europe, is legally defined as an “asylum procedure that shall be conducted prior to the decision on entry” to the territory. It can only be carried out if the asylum seekers can be accommodated at the airport during the procedure and if a branch of the BAMF (the German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees) is assigned to the border checkpoint.

FRAport—Frankfurt Airport—is the only airport that has such a reception department. This area, which is difficult to detect on the airport map, is situated in the cargo facilities. In 2015, 627 asylum seekers went through the airport procedure, according to BAMF, with Frankfurt Airport as Germany’s busiest point of arrival. Of those 627, 549 were allowed entry. Of the seventy-four rejected applications, seventy-two led to appeals, of which just two were upheld.

The failed asylum seekers’ length of stay in transit accommodation depends on how long it takes the federal police to arrange the necessary paperwork for their return. In the accommodation at Cargo City South, people have access to a football pitch, a fitness studio, and a basketball playground. There is a telephone and a television room with a selection of DVDs to pass the time.

As the example of Nazil Wakir shows, most asylum seekers reach the airport illegally and have to wait up to fourteen days. As the website Asylum in Europe reports, “the denial of entry, including possible measures to enforce a deportation, is suspended as long as the request for an interim measure is pending.” If there is no legal decision within fourteen days, the asylum seeker has to be granted entry. Except for applications marked by authorities as “manifestly unfounded,” in the majority of cases, asylum seekers are allowed to leave the airport in order to follow the regular procedure. If the appeal is rejected the person will face deportation. There is no clarity on how long this will then last.

At FRAport, then, people might be denied entry and sent back. The airport indicates its property as a border not only because it re-deviates by rejecting asylum seekers; it is also the main place from which general expulsion processes take place. In 2017, out of a total of around twenty-one thousand deportations by air, 6,756 took place from Frankfurt.

In the first half of 2018 there were a total of 11,005 people deported by air. People were sent back to Italy, Albania, Macedonia, Bosnia, and so on. Nobody has been sent back to Syria, but of those being sent back, 502 were of Syrian nationality. Between January and September 2017, 222 planned deportations were classified as “failed” due to pilots who refused to carry out the deportations. This included 140 failed deportations at Frankfurt airport alone. Pilots can face disciplinary measures if they refuse to fly on moral grounds. But as the spokesman of Lufthansa Michael Lamberty claimed, the official reason pilots didn´t fly deported people was due to security concerns.

The airport produces a new social space in its own way, one that we enter only thanks to our identity. But what is left out or what is kept hidden can tell us a lot about a different negotiation of time and of a process of bordering. Our temporalities differ. Some might stop at passport control and it will take around a few minutes. Or at the security checks, for some it takes minutes, for others it is about two days, if not fourteen. The airport is thus a space where we encounter a process of bordering that not only affects the direction of our movements, but also the time we spend in and out of transit. It might also become a zone of contestation, where borders are negotiated and negotiable, where these same processes are re-discussed. I draw on Thomas Nail’s argument that “the border is an active process of bifurcation that does not simply divide once and for all, but continuously redirects flows of people and things across or away from itself.” In my counter-mapping, I have wanted to show that an airport is not only a place where fluxes are enabled, but also where those same human fluxes can be redirected or rejected. Data visualizations might give us the impression of a highly connected world where people are free to travel between airports. Instead, airports reproduce a specific social space, where processes of bordering might become even more explicit.