Society for Sick Societies is a diagnostic project. Built as a series of episodes, each one of its vignettes sets out to analyze an expressed symptom of a sick society–a practice, pattern, gesture, proverb, or technique that seems to encapsulate social malaise in pseudo or post-democratic societies. The triple S is critical theory’s first aid to a state of crisis, probing sickness as both real and symbolic, affecting the biological body, the social body, and the body politics. The series is edited by Laliv Melamed.

In a world in which individuals who are naturally at risk confront each other in a competition whose stakes are power and prestige, the only way to avoid a catastrophic outcome is to institute among them sufficient distant so as to immunize each other from everyone else […] From here the need arises for strategies and control apparatuses that allow men and women to live next to one another without touching, and therefore to enlarge the sphere of individual self-sufficiency by using “masks” or “armor” that defend them from undesired and insidious contact with the other.

-Roberto Esposito

A snapshot of a woman standing by the window and waving to the camera has gone viral among Israeli users of social media. At a first glance, the white plastic blinds and the underwear slung outside seem like nothing out of the ordinary. But a closer look reveals that these are not underwear but masks disinfecting in the spring sun–perhaps the ultimate signature of a crisis, routinized. The caption suggests that this snapshot was taken by a police drone that hovered outside of an apartment building to make sure that the inhabitant, the woman in the picture, is in quarantine. She obeys by waving to the machine: “I’m here.”

The drone provides an exceptionally striking photographic image within a much wider surveillance apparatus deployed by Israel to cope with the outbreak. The Israeli government, perhaps more than most states, was quick to introduce particularly strict lockdown measures. By triggering numerous emergency regulations the government significantly expanded the executive powers of the Israeli Security Services (Shin Bet), which openly deploy intrusive technologies in order to track the activities of citizens. (See Laliv Melamed’s contribution in this series.) The immense apparatus of surveillance has emerged from the murky waters of emergency like the back of a white whale. Prepared to cope with the invisible threat of the virus, the weapons that are regularly aimed at the Palestinian population are now targeting lawful citizens. Approving unlimited telecommunication tracking and data mining have been a grand opportunity to sharpen the scale and resolution of control around the individual civilian and his or her body.

But the rapidly expanding executive powers that regularly operate in a top-down structure expose only one half of Israel’s Janus-faced state of emergency. Once fear penetrates deep into civil life in Israel, other and far more elusive strategies are activated, most of which seem like the very opposite of centralized state power. A closer examination of Israel’s modelling of emergency reveals regulations that expand the freedoms of individuals to cope with external security threats. And at the heart of these regulations lies the private home as a shell in a defensive society wherein the individual is not merely the target of state power but also its core agent.

Indeed, alongside the emergency regulations that Israel used to allow the close monitoring and surveillance of its citizens, it invoked the civil defense regulations that were drafted in 1948 and adopted as a basic law in 1951. The 1951 document Civil Defense Regulations articulates the main goals as procedures aimed at mobilizing civilians during times of national emergency. Civil Defense regulations are meant to define a channel of communication between the state and the individual civilian. Instead of reproducing the inert subject of disciplinary power through demands and orders, this so-called individual is actively and intimately engaged in matters concerning his or her own defense. Effectively, these regulations define the roles and obligations of isolated individuals at times when the state fails to perform its tasks. Civil defense is defined as “the defensive layer whereby the individual harnesses any available means to minimise threat through the use of technologies, individual defense kits and the preparedness of the private household for crisis.” “The responsibility of one’s safety,” the document continues, “is in the hands of the individual himself.”

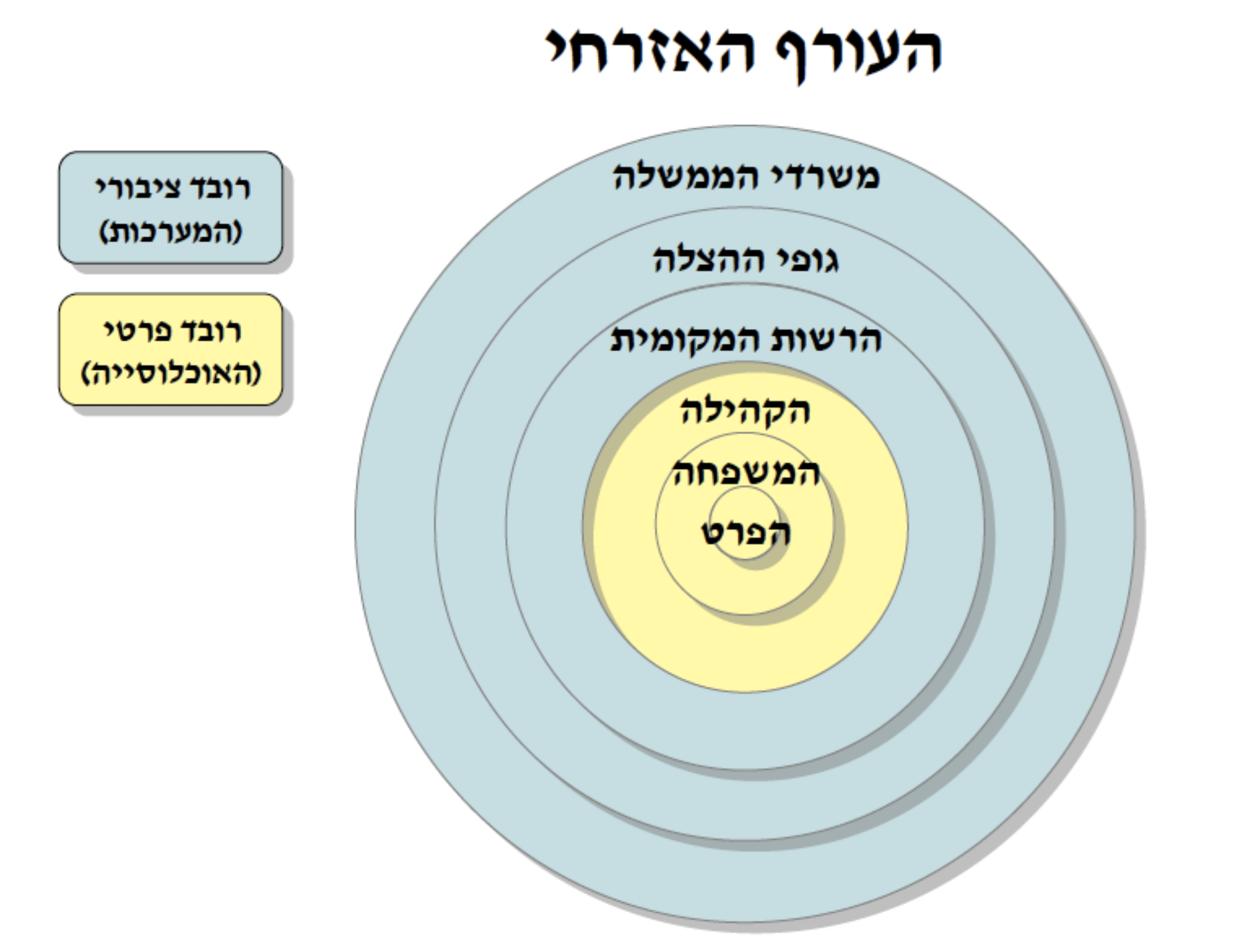

The regulations imply that in times of emergency the borders of the state shrink flexibly to fit the walls of the individual’s household. The escalation of risk feeds the need for individuals to act for themselves and seal their homes. This is illustrated by diagrams elegantly drawn within the civil defense protocols. Onion layers of “protective shields” begin with the outermost shell and continue inwards to the center and core of “security.” At the heart of the diagram, the individual appears isolated from the world, enveloped by a family, a community, and national borders that orbit around the inner spheres. According to the Civil Defense Law of 1951: “the more the individual, his family, and the household take effort to follow civil defense regulations, the more misconduct and panic are prevented.”

The 1951 Civil Defense Law reflects the strong ties between the military and civil sectors of Israeli society. One of the most important factors enabling the strengthening of these ties was the promotion of the idea that there is a ubiquitous and constant threat to the very survival of the Israeli state. “Israel’s national security policy,” writes Anver Yaniv, “begins from the assumption that the Arab-Israeli conflict is inherently and unalterably asymmetrical and that the Jews are and will always remain the weaker party.” Civil defense regulations were shaped according to this contested notion of threat. The law backed the assumption that “Israel must eliminate the common but pernicious misconception that the army alone can guarantee state security.” Security, consequently, must be habituated, domesticated and personalized.

The program for imbedding civil defense regulations into everyday was largely inspired by the United States. In the early to mid 1950s the US government invested substantial scientific and economic resources in order to reimagine the private sphere as the ultimate defense against nuclear warheads. Israel’s civil preparation for wartime routine followed US President Truman’s lead. At the time the Israeli Civil Defense Law was passed, Truman had just inaugurated the new Federal Civil Defense Administration. Focusing on the private home and its maintenance, the state in the early 1950s sought to “emotionally manage” citizens through fear. By militarizing everyday life, civil defense authorities attempted to both normalize catastrophic danger and deploy an image of it politically. Both US and Israeli civil defense officials suggested that citizens should be prepared every second of the day to deal with a potential aerial attack. “It was up to the citizens to take responsibility for their own survival.” Jackie Orr has powerfully shown that by unleashing panic, “the national security state remade the individual as a permanently militarized node in the larger system.” The state’s central strategy, both in Israel and in the US, was to empower the individual to take control over his household. The strategy was predicated on the capacity to contain panic while, at the same time instilling fear. Fear, it was imagined, was a sort of immunization against contingency, an “emotional inoculation” of the public.

Inspired by the Second World War military policies in the United States and the United Kingdom, the newly organized Israeli Defense Force identified the need to communicate directly with the civil sector. A direct communication line between the military and civil sphere was advanced by a Jewish lawyer in 1944. Lieutenant Mordechai Nimsabisky approached the British Mandate officials in Palestine to acquire special permission to arm civilians against the “Arabs in the region.” Under his advice, the “Civil Section” of the pre-state defense organizations recruited new immigrants who had arrived from Germany as Zionists to form a paramilitary civilian task force. Taking his prime example from the British “Home Guard,” the zealous Lieutenant Nimsabisky opened the Civil Guard Office to advise the Jewish Agency in matters pertaining to the mobilization of civilians. With extensive experience in print advertising and propaganda, Nimsabisky foresaw in 1948 the opening of the Civil Defense Office.

The office produced a poster that showed a man standing on the balcony of his home looking outside to watch the spectacle of bombs coming from above. Behind him, his family sneak a peek with dread while a 250-kilogram bomb is on its way to land near their house. The informational campaign distributed by the Civil Defense Office singled out the private domain of the household as the best available shelter against aerial bombing. A large caption in Hebrew says “curiosity risks life.” The campaign was part of the plan to appoint an individual that would oversee every household at times of emergency. A member in the family would be elected to act as a “Domestic Inspector” who would be a competent individual within a given family and who could take responsibility for policing the home. In the words of the Civil Defense Office: “an efficient organization of self-defense within the home may prevent misery and save human lives (…) the ‘Domestic Inspector’ is thus responsible to communicate between the residents of the household and the army.” The appointed “Domestic Inspector” was meant to wear a tag on his shoulder bearing the symbol of a wide-open eye. This eye would, perhaps, extend the state’s vision. Most significantly, the domestic inspector was put in charge of communication in the event that state technologies failed to inform civilians at home about the unfolding events outside. This embedded failure of communication between the level of government and citizens was intended to be understood as another protective layer or immunization against external threats.

At times of emergency the domestic inspector was to be in charge of communication, but he was equally responsible for facilitating the separation between homes. John Durham Peters notes that the Latin communicare, which means sharing, is often invoked as the only origin of the meaning of the word communication. Rarely cited but equally relevant is the Greek term koinoō, which has harsher implications. Like communicare, it means to make common, communicate, impart, or share—but it also entails dividing, separating or quarantining. This etymology of the word communication suggests precisely the opposite of what we usually think of as communication and alludes to the inherent separation between civilians as a prerequisite to communication. Perhaps the domestic inspector is an ideal figure of a defensive society, divided and fragmented into households, each standing independently but remaining directly connected to the state. Although the plans to appoint domestic inspectors were never officially implemented, the trope is activated today by the push and pull between restrictions and freedom at times of crisis.

The coronavirus redraws the contours of the individual as both the target of state power and it most valuable agent. The centrality of the individual in the discussions of security at times of emergency draws the outline of a liberal individuality fundamentally predicated on access to the home. “Having a property in one’s own person is the ultimate point where propriety meets property,” writes Etienne Balibar, “where to be rejoins to have.” The external frontiers of the state are recast through civil defense as a projection and protection of an internal personality, which each individual carries within him or herself. If the woman by her window stands as the target of state power, the man on the edge of his porch is the extension of it. The man on his porch operates according to a governing rationality that is no longer one of strict regulation and disciplinary power; rather, it grants a degree of freedom to individuals. The pandemic, more than any other threat in the history of the Israeli state, fragments the collective identity to make way for an isolated and insular individual, who has access to a household from which he or she can communicate with the world. Both the woman by the windowpane and the man in his pyjamas on the porch of his home remind us that at times of emergency Israeli citizens occupy the threshold between inner and outer, private and public, individual and collective. And while the exposure to public life comes through the window as the fundamental feature of what constitutes an individual, today that bare condition of exposure is gradually being disconnected from its relation to communal forms of life. Under the threat of the virus Israel can draw a clear separation from the historical formation that shaped the self through the encounter with others, to replace it with a “domestic inspector,” an independent civilian defined through self-sufficiency and risk containment, a dweller that embodies the state.