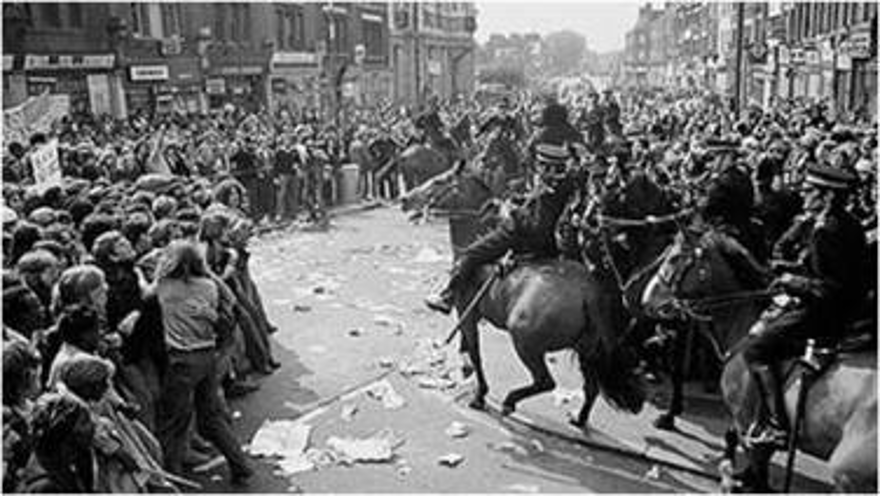

Every day for the past two years, I have heard horses ride down the road outside my flat. There are always two of them, and they always take the same route, down the hill and round the corner before their hoofbeats once more echo off into the distance. They are police horses on their exercise routine: Lewisham, where I live, contains the largest purpose-built police station in Europe. Historically, the area has also been a scene of vital anti-fascist activity, most notably the 1977 Battle of Lewisham, in which a march by the National Front was roundly defeated through principled and physical resistance. While the Battle itself was a defeat for the NF, who’d not expected the resistance they encountered, its aftermath involved a retrenchment of right-wing state policy. Margaret Thatcher absorbed the tougher immigration stance that had won the NF support and hurt the conservative’s electoral chances—a tactic clearly still in use today, as conservative border policy becomes steadily more racist, and more overtly so; additionally, the battle was the first time that officers lined up with riot gear on the UK mainland. Vast numbers of cops—around a quarter of the entire Metropolitan Police force—were deployed, along with horses, which, as recently discovered footage shows, aggressively charged protesters, prefiguring the infamous charges at Orgreave in 1984. The Metropolitan Police at the time were known to target and brutalize people of color, often in relation to spurious drug charges. It would hardly be a surprise to anyone that stop-and-search operations during the present period of lockdown have been disproportionately targeted at people of color. Or let’s call it by its name: racial profiling. Plus ça change. The current Police Station contains stables for around twenty horses. When they pass the flat, they trot serenely, sedate in the power they incarnate. Yet invariably when I hear them, I’m put in mind of a protest chant: “get that animal off that horse.” The chant remains unsounded, a voice in my head trailing off into the sounds of traffic, birdsong, muffled sirens. On other occasions, I see police horses—the very same that exercise on my street—block off roads, corral or ride down protestors on foot, as a tool of intimidation that goes by the euphemistic name “crowd control”: most recently, at a Black Lives Matter counter-demonstration on June 13, 2020, when a group of far right hooligans gathered in Central London to “protect monuments” from anti-racists. The previous weekend, Black Lives Matter protesters—many of them teenagers—had marched en masse for two days in a row in furious, sorrowful, and defiant solidarity with the protests against police violence in the United States and at the racialized effects of the virus in the UK, saying the names of George Floyd and of Belly Mujinga, a transport worker who died after being spat on by a passer-by infected with coronavirus, and whose death received a predictably desultory and inconclusive investigation. On the first of that previous weekend’s demonstrations, predictable media outrage erupted when a mounted police officer collided with a lamppost, the horse bolting through the crowd. Far better charge the crowd than fall from your perch. Home secretary Priti Patel—who sees protest as “thuggery” (apparently the favored word in use amongst right-wing and centrist politicians at these times) and who, along with “Justice” Secretary Robert Buckland, is keen to impose punitive sentences on those committing “public disorder”—visited the horses in Lewisham, as the South East London News Shopper reports. Predictably, Patel showed more interest in condemning “hooliganism” from protestors and more concern for a horse—with which she is apparently on first name terms—than for those who have died from COVID-19 or the victims of police violence in the United States.

Patel’s apparent affection for the horse with which she’s seen above has a history. Horses, like children, were simultaneously figures of sentimental attraction and ruthless exploitation during the industrial hells of the Victorian era. Treated with unbelievable cruelty, the workhorse, as opposed to the imperial steed, was a creature of labor, worked (often literally) to death as part of the daily operations of production and subsistence, while being sentimentally depicted as a creature of near-human elegance and intelligence in literature and art. Humans also functioned as, or even as subsidiary to, workhorses. Karl Marx noted that: “in England women are still occasionally used instead of horses for hauling barges, because the labor required to produce horses and machines is an accurately known quantity, while that required to maintain the women of the surplus population is beneath all calculation” (517). And on plantations in the British West Indies, slaves had the function of walking behind their masters and literally holding up the tails of their horses. The widespread usage of horses went into decline in the early twentieth century as mechanization took over functions of travel, labor, communication, and trade in which horses had previously been indispensable. This is often taken to be illustrated through the massacre of cavalry by newly-invented tanks during First World War campaigns, the loss of horses somehow a worse horror than the more usual loss of human life. Horses still haunt these modes of transport—most obviously in the metaphor of “horsepower”—but increasingly take their place in elite leisure activities: witness the aristocrats in absurd hats, infecting each other with COVID-19 in one of the last mass gatherings before UK lockdown, the Cheltenham Festival of March 2020. In the UK, horse-riding is an activity generally reserved for cops and aristocrats, illegally hunting for foxes, or, legally, hunting for protestors. Emblematic of a class-based split between the rural and the urban, horses enter into public life as part of the vestiges of state order, the conscious display of tradition and the exercise of public authority in such redundant and nostalgic functions as Trooping the Colour outside Buckingham palace.

While horses are generally taken to have a ceremonial or picturesque function, they have increasingly been used in the UK for “riot control” purposes since the 1960s and 1970s. In urban areas, protests are one of the only places you’ll actually see a horse in public. At the 1968 Grosvenor Square anti-Vietnam War protests, horses charged the crowd and protestors rolled marbles on the street to break up the charges. The Mounted Branch of the Metropolitan Police had been founded in 1760, predating the establishment of the modern police service itself in 1829: patrols set up to intercept highwaymen and fleeing criminals on the outskirts of the city, they wore the first uniform issued to any police force in the world. Initially used on the city’s edges, they began to conduct urban patrols and were incorporated into Robert Peel’s police force in 1836. British models of mounted policing spread across its colonies in the nineteenth century, throughout Africa, the Middle East, India, Canada, and the Pacific colonies. Whether subjugating colonial populations on the periphery or subjugating the disenfranchised in the colonial center, horses came to play an important role in regulating industrial and surplus populations, a process that involved often ferocious violence. (Whether those horses were ridden by the army—as in the 1819 Peterloo massacre—or by cops is perhaps a moot point.) Colonialism also saw the spread of horses to the American continent, where they had been extinct for thousands of years before Christopher Columbus, Hernán Cortés, and others brought them over, a number of the animals escaping as wild horses. Within the antebellum plantation system, horses’ lives were valued at an equal or superior level to those of the enslaved people forced to tend them. Horses also served to regulate the boundaries, bringing back fugitive slaves. The slave patrols were so central to the geographies of antebellum states that, as Walter Johnson notes in River of Dark Dreams, “the geographic pattern of country governance in the South emerged out of the circuits ridden by eighteenth-century slave patrols.” “For slaves on the road,” he writes, “the sound of an approaching horse was a fearful portent”: horses enabled slaveholders to “visually command the landscape” and to run down slaves fleeing on foot along the roads (222). Horses were all the more effective because, while they functioned as extensions of the slaveholder’s human agency, it was also unclear to what extent horses “remained the agents of their own actions.” Tellingly, Johnson links this element of fear and unpredictability to the contemporary use of horses to suppress dissent.

As anyone who has ever observed the employment of horses in ‘crowd control’ can attest, the unpredictable, uncontrolled character of horses makes them especially terrifying to those against whom they are deployed. A horsed added a fearful layer of wildness to the already volatile encounter of a white man and a slave on an isolated road. (223)

Slaveholders played on the fears generated by the essential unpredictability of the horse—its liability to run wild and loose, against directive—by tethering slaves to the horse, where they faced the risk of being dragged or trampled beneath its hooves: a harnessed capacity for spontaneous, unregulated violence typical of a plantation system which balanced “rational” control and irrational supremacist brutality. Horses also participated in the expansion of the “frontier,” whether through farming, cattle drives, or charging down the Native Americans who were being driven off their land and “relocated” to positions of increased confinement. That balance between confinement and expansion, used to subjugate imported and native populations through a logic of racialized violence, is central to the movement embodied in the horses of slaveholders, of the US cavalry, or of the police. Not for nothing have numerous radicals made the plantation/reservation analogy for twentieth-century inner cities. It’s been well-documented that the modern US police force has its history both in the regulation of immigrant populations in Northern cities such as Chicago, and in Southern slave patrols—a “transitional police type” performed by citizens as civic obligation in return for pay, tax exemption or other rewards, evolving into the police force that controlled the movement and activities of now freed African Americans. In August last year, mounted cops in Galveston, Texas led a handcuffed African American by a rope in an explicit echo of such patrols. KRS-One’s wordplay in “Sound of da Police”—“overseer overseer overseer overseer / officer, officer, officer, officer”—is more than merely a clever pun, but a reminder of the history incarnated in the figure of the cop, especially the mounted cop.

All this passes through my mind as I sit here and hear the horses clip-clop past, inside the flat in which I’ve spent virtually all of my time these past three months of COVID-19 lockdown. This confluence of fascists and cops, of the history of colonialism, enslavement, and the management of dissent, exacerbated by the ever-present horizon of the global pandemic, seems to shape everything these days, like a series of tripwires stretched across a road towards whatever we could call a better world—by which it sometimes seems we mean little more than one that is merely liveable. John Henry Fuseli’s 1781 night mare comes to life: the bug-eyed horse straining at the edges of a somnolent hallucination, as or more real than waking life.

Back in the daylight world, it’s hard to flee a charging horse. On foot, running to or from scenes of protest and confrontation, the advantage is had by those with horses, vehicles, helicopters. Yet, as Walter Johnson shows, fugitive slaves also used horses to their own advantage. In particular, horses provided them with a way to explain their presence on the open road and evade capture: “for slaves, hunting a lost horse was often the most plausible explanation for being away from home. When William Hayden and Henry Bibb ran away, they both took bridles with them as a sort of counterfeit pass.” (288) The velocity of a horse, able to traverse land far quicker than any escapee on foot, could be used as cover, as enslaved people pretended to have travelled by wagon or horse. And on occasion, enslaved people were even able to “turn” the slaveholders’ horses in their care and ride to freedom. As Bénédicte Boisseron argues in her recent Afro-Dog: Blackness and the Animal Question:

The sight of blacks on horseback brings to the mind the hysterical fear of black freedom of movement, black horseback riders like [Toussaint] L’Ouverture being associated with dominance, rebellion, and disobedience. From slaves being on foot while masters are on horses to free men of color being required to dismount their horses when reaching the gates of cities to runaway slaves stealing horses, the act of riding a horse has always been a symbol of freedom determined by race in America. (52-3)

The horse, with its suggestions of grandeur, leadership, and military power, is a symbol too often denied African American representation, but all the more powerful when it appears. Memorably, Ras the Exhorter—turned Ras the Destroyer—rides a horse through Harlem in the climax to Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, a hallucinatory version of the 1943 Harlem riots.

They moved in a tight-knit order, carrying sticks and clubs, shotguns and rifles, led by Ras the Exhorter become Ras the Destroyer upon a great black horse. A new Ras of a haughty, vulgar dignity, dressed in the costume of an Abyssinian chieftain; a fur cap upon his head, his arm bearing a shield, a cape made of the skin of some wild animal around his shoulders. A figure more out of a dream than out of Harlem, than out of even this Harlem night, yet real, alive, alarming.

“Come away from that stupid looting,” he called to a group before a store. “Come jine with us to burst in the armory and get guns and ammunition!”

Though he himself demurred on the connection, Ellison’s Ras, at this moment, has generally been assumed to draw on Black nationalist orator Marcus Garvey, of whom a contemporary Philadelphia magazine exhorted:

Ride on Marcus Garvey. Thinking men and women are with you. Let the Black Horse ride and hold the balances high that the world may see justice for all mankind.

There are perhaps closer echoes, however, of the lesser-known Black nationalist Grover Cleveland Redding, head of an organization known variously as the “Star Order of Ethiopia” and the “Ethiopian Mission to Abyssinia.” A year after the brutal violence of the 1919 Red Summer, in which white mobs had rampaged through Black neighborhoods in Chicago, Redding led a parade along 35th Street astride a white horse, wearing a toga he claimed to be the costume of an African prince. The parade was a statement of pride and of hatred for a government that still counted Black lives as less than human. As Redding stopped the parade to burn not one but two American flags, a Black police officer intervened, accusing the Abyssinians of being traitors: along with a white sailor, soldier, and storeowner, he was shot and killed by Redding’s followers. A kind of anti-slave patrol, Redding’s parade saw roles reversed: now the mounted African American shoots the policeman (also African American) on foot. Executed for murder the following year, Redding’s last words were “I have something to say, but not at this time.”

***

Untimeliness haunts the image of the horse and rider: the image of the African chieftain, in Redding’s case, or the quasi-military outfits of Garvey’s UNIA, uniforms for an unrecognized nation. But untimeliness is also timely, and it was almost exactly a hundred years to the day of Redding’s ride that footage circulated of another horseback rider tearing through the streets of Chicago during a Black Lives Matter protest—simultaneously a kind of apocalyptic herald and an act of sabotage, fugitivity and counter-occupation. (“Whose streets? Our streets!”, as the chant goes.) Rumors spread, based on footage of the rider apparently claiming “I stole it from the police!”, that the animal had been snatched from those who’d been brutalizing protesters, though these soon turned out to be false: the horse was in fact owned and ridden by “the Dreadhead Cowboy,” Adam Hollingsworth, who has ridden up and down Chicago streets during the eerie silence of lockdown and continued to ride as those streets exploded in the wave of protest sweeping the country following the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery.

This week, Hollingsworth rode around Cook County Jail in Chicago’s Little Village neighborhood. During his ride, he said he spent 18 months in jail. He was charged with possession of a firearm and possession of a stolen motor vehicle in 2006. He was a teenager then and said he was wrongfully charged. He said he rode around the jail for “all the innocent people” inside the county jail […] When asked if he’s concerned about being out during this pandemic, Hollingsworth noted that it’s always dangerous to leave the house as a black man living in Chicago. As for the threat of COVID-19, he said he’s six feet apart when he’s up on the horse.

The wild ride of the Dreadhead Cowboy is the negation of the police horses that ride down my road with the serene authority of the state, the negation of the horses of the slave patrols and their ancestors in contemporary policing. Evoking the image of the “Abyssinian” Black nationalist, or, more explicitly, the Black cowboy, in a city which played a key role in the formation of modern American policing, he rides at once out of present and past. Others have followed suit. In Oakland, Brianna Noble joined a BLM protest on her horse: “when you’re black it doesn’t matter how loud you scream or how deep your words are, nobody would listen […] I thought to myself: ‘I’m just another protester if I go down there alone, but no one can ignore a black woman sitting on top of a horse.’” In Minneapolis, a protestor amongst the crowd stood on his horse, giving the police the finger (both of them). In Houston, two dozen members of the Nonstop Riders rode up to join the crowds, the additional battalion echoing the use of horses by Native American protestors protesting the Dakota Access pipeline; these images all serving as a defiant challenge to that of the man led by horseback police in Galveston the previous year.

On October 13, 1806, the day the city of Jena fell to French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, G. W. F. Hegel wrote to Friedrich Niethammer: “I saw the Emperor—this world-soul—riding out of the city on reconnaissance. It is indeed a wonderful sensation to see such an individual, who, concentrated here at a single point, astride a horse, reaches out over the world and masters it.” For Hegel, this horseback rider, imperial and imperious, embodied world history. But it was the earlier liberation of Haiti under Toussaint l’Ouverture—himself a gifted equestrian—that was the true world-historical event, extending and fulfilling the radical promise of the French Revolution and its 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man, and Napoleon—who had reversed the Declaration’s Abolition of Slavery—who incarnated the partial vision of world history as white supremacy.

Against the Napoleonic figure assuming the position to which he will then have always-already been entitled, the Dreadhead Cowboy rides from the ranks of those systematically erased from such a conception of world history. Competing visions of history are at stake. This a war that takes place today—as it has always done—on the streets as much as at polling booths, in the riot as much as in the election, in protest movements as much as in military campaigns, in the fight-back against the daily violence of white supremacy as much as in the trumpeted conquest of subjugated cities by generals, mercenaries, and liars. The Dreadhead Cowboy’s ride is a moment of street lore which cracks open the official narratives of containment and looting, “disorder” and control: ludic yet purposeful, alive with the exhilaration of the unprecedented, of taking a course for which, unlike any number of history’s supposed white heroes, the way has not been paved. Unlike Hegel’s Napoleon, incarnating world history while leading a conquering army into a conquered city—or, for that matter, today’s would-be Napoleon, President Donald J. Trump clearing a peacefully-protesting crowd with troops for a photo opportunity outside a church—the horse rides by on the margins of the action, captured in a grainy video clip shot on someone’s phone, posted anonymously, surrounded by rumor. The apparently anachronous figure of the Black cowboy is another historical fallacy: there’s a rich history of Black cowboys, male and female, whitewashed from the Hollywood history that built familiar mythology out of the recent past. Emerging from the anonymous mass of the dehumanized, criminalized, and systematically exploited, the Dreadhead Cowboy serves as exemplary figure of marginality and the “freedom dreams” smuggled as fugitive contraband through what Robin D. G. Kelley has named as the “Black Radical Imagination.”

The Dreadhead Cowboy may not be one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse imagined by John of Patmos in the Book of Revelation—a visionary protest written in the heart of another empire—nor Hegel’s exemplary figure of Napoleonic grandeur, but as much as either of these figures are enshrined in Western teleological traditions, his arrival should be taken as a kind of annunciation. This is also an anti-teleological movement. In the tradition of Western liberation, both sacred and secular, a force moves to its end, incarnated in and represented by exemplary White Male Heroes. In the Biblical account, the Four Horsemen signal the making of a new heaven and a new earth through literally world-destroying conflict. Poet D. Scott Miller’s “Afrosurreal Manifesto” however, presents the Biblical heralds of apocalypse as having been and gone, a revelation of militarized police violence and a society predicated on anti-Blackness that for so many is an already-lived reality. “The Tasers are here. The Four Horsemen rode through too long ago to recall. What is the future? The future has been around so long it is now the past.” Robocop walks the land, seamlessly merging with the revenant forces of the Klan, the Statues of Confederate racists, and their vigilante descendants, whether toppled or standing.

The Dreadhead Cowboy’s stated aim is to teach other, younger kids to own and ride horses as image of aspiration and empowerment—an eye to another future. Rather than ride with others in Chicago’s Black Cowboy community, he prefers—as if straight from the pages of a Hollywood Western script—to ride alone. In contrast to the familiar sight of a phalanx of regimented, mounted police, his wild freedom to move is a force of retreat as well as advance. And while it comes to life in moments of social unrest, as autonomous zones are established and the police—that permanent army of occupation—are pushed back, the fear will always be that the cowboy’s horse is replaced by police horses, police cars, the ambulances that bear away those they have killed. Yet who could have foreseen the swell of resistance across the United States—and the world—that one more police killing sparked off. Who could have foreseen the president hiding from anti-racist protestors in a bunker beneath the White House? Who could have foreseen serious discussion of proposals to abolish—not just “reform,” not even just “defund”—but abolish the police and the carceral system?

The enigmatic epigraph to Theodor Adorno’s In Search of Wagner reads “horses are the survivors of the age of heroes.” But History doesn’t ride in as an emperor taking a tour of a conquered city, and any nostalgia for war horse over workhorse would be false. All horses, save for wild ones, are workhorses, and all workhorses, like all human workers, are survivors of the world they build and from which they are cast aside. Black Cowboys existed at a complex intersection of freedom and labor: released from slavery, they faced a hard life on the frontier, participating in the “building of America,” that project for ever-expanding territorial sweep predicated on genocidal clearance of wild animals, of people, the spread of disease, the imposition of hypocritical values of lawless law. Horses were and are working animals, and these horses were ridden by those who until that moment had themselves been treated as beasts of burden, workers torn by the status of having to be rendered simultaneously human and non-human. We should read the ride of the Dreadhead Cowboy, not as the return of some latter-day Black Napoleon, but outside the narrative of heroes, emperors, leaders and world-historical subjects, and into the category of those whose presence was systematically erased from national self-mythology in order for the fiction of whiteness to exclude all that it found inimical to its self-definition, and on which it relied for its very existence. The narrative of the White Male Hero perpetuates the exclusionary violence of national and racial self-identification incarnated in the white cowboy, cop, member of a right-wing militia, the multiple archetypes from which the current racial conjuncture freely and wildly draws. Such heroization has its roots in the narratives of the bourgeois revolutions, in the work of Thomas Carlyle all the more so than Hegel.

Meanwhile, in present-day England, the term “hero” has recently taken on an unpleasant double valence, its residual association with a kind of nostalgic affection for the military extended to the entirety of public life in the militarized, “Blitz spirit” used to conceptualize lockdown. In particular, the term has come to be applied to nurses, doctors and other health workers whose deaths through inadequate provision of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) its usage seeks to both cover up and justify. It is also applied to any “front-line worker” whose continued circulation through urban spaces exposes them to the virus, yet whose racialized and class position often gives them no other choice. In the wake of the BLM protests whose technically illegal assemblies served as the defiant repudiation of the jingoistic mass gatherings taking place on VE Day—the now-infamous White People Conga Lines—at which the government raised nary a word, Priti Patel and her lackeys in right wing media rags described the mounted police at the demonstrations as “heroes,” particularly if they fell off their horse. “Proud to stand with these brave men and women” proclaimed Patel at Lewisham police stables, as if the police were an army resisting invasion (also a favorite metaphor of Boris Johnson’s). Neither Johnson nor Patel—nor, for that matter, Donald J. Trump—are habitual horse-riders, as far as I’m aware. It’s unlikely, though, that even if they were—something which would be more than symbolically apt—anyone would really regard them as heroic. Like much militarized imperial nostalgia, the specter of the hero is deployed to compensate for the failed promises of wealth, prosperity, and national belonging it attempts to cement. Likewise, Adorno’s enigmatic statement about the survival of the horse from the age of heroes might imply that the horse has unseated its “heroic” master. “The horse has bolted,” as it were. Good riddance.

In a scene from Béla Tarr’s film, Sátántangó, a herd of horses inexplicably sweep through a town square in the early morning. The herd fills the screen for several minutes, witnessed only by three passing travellers, before disappearing again. Their origin and location is unclear until a line of dialogue pragmatically informs us that they have escaped from the slaughterhouse: that this is, in other words, a habitual occurrence. Struggles for liberation are perpetual attempts to escape the slaughterhouse or the knacker’s yard: the glue that holds society together is made from bones and discarded corpses. But imagine Tarr’s herd instead as a herd of police horses that have unseated their riders and continue to roam the streets. The panicked animal that lost its rider to the lamppost on June 6 and tore indiscriminately through the crowd of protesters was eventually retrieved. But imagine if that fleeing police horse had continued to ride in freedom—albeit a panicked freedom, a freedom of fugitivity: through the streets, away from Parliament Square, away from Westminster, the seat of government; over the river, south through the city; along the now near-deserted streets of Lewisham in lockdown; past the enormous police station from which perhaps it came; back up Belmont Hill, which in 1977 had been the scene of a police charge against antifascists striving to “clear the streets”; through the extended conurbations built on what used to the be the edge of the city; tearing through the fields controlled by Tory farmers; wreaking havoc in the enormous gardens appended to the second homes of the super-rich where, perhaps, they were sheltering from the pandemic; and on to the shoreline where “Fortress Britain” replicates and defines itself against “Fortress Europe,” seeks to banish the principle of shelter, compassion for the stranger, the openness of borders, where the lapping of the waves resounds like gunshots or thunderclaps. Imagine that fleeing police horse joining up with the spirits of military horses, police horses, workhorses who worked and died through the ages, the spirits of the protestors, combatants, and innocent civilians they have mown down; the horses of the Black cowboys excluded from history, of those riding to freedom, with the horses of latter-day Black cowboys, from the Dreadhead Cowboy to Brianna Noble and the Nonstop Riders. Perhaps the ending of the world as it is currently constituted will be signalled, not by the ride of a heroic leader astride a horse—whether Napoleon, Toussaint, or John Wayne—nor the mass charge of police horses, nor the last-minute entry of the Seventh Cavalry, but instead by the rumor of a stolen horse and the collective, leaderless gallop of insurgents who ride in from the side: twenty-first century cowboys come, not to perpetrate genocide, but to end it, not to ride down protest, but to extend it. Instead of the reconnaissance of one individual, concentrated at a single point, who surveys the world and masters it, countless other horses, literal and metaphorical, their riders named and anonymous, riding through the streets of those cities the general thinks to conquer, overturning that surveyed and mastered world to make history of a different sort.

Cover image: Runaway police horse, Black Lives Matter Protest, London, UK, June 2020. Screen capture from news footage.