Mayor Bloomberg’s appointment of Marc Ricks, a vice-president at Goldman Sachs, to the team overseeing the Hurricane Sandy recovery efforts was an early indication that the crisis might be used, in classic disaster capitalist fashion, to promote deregulation, reduce public services, and reward entrepreneurial business development. Studies of economic reconstruction after Katrina and 9/11 showed how market-centered policies focusing on tax breaks and private sector subsidies were systematically favored over direct government outlays, allowing developers to prosper at the expense of the public benefit.

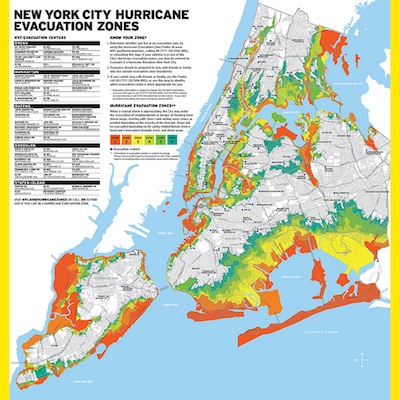

In the wake of Sandy, the face-off about the future of the city’s waterfront offers stark choices. Should residents retreat altogether from the 100-year flood zone A in the face of near-certain inundation, or should developers be green-lighted to build fortified enclaves capable of withstanding storm surges and tidal encroachment? Much of the city’s public housing is situated in flood zones A or B, and so either option will once again entail the involuntary displacement of populations that were pushed out of more central locations by urban renewal programs in the 1960s and 1970s. In the last two decades, New York’s waterfront was increasingly targeted for upmarket development, and so its communities have been in transition from low-income to high-income. The latter fared a lot better during Sandy, bolstering the developers’ argument for fortification. But what the developers value–the rising commodity price of waterfront land–is now in direct conflict with the social character of Zone A land to act as an absorbent buffer of water from storm surges, as wetlands have traditionally done.

Mayor Bloomberg’s support for the developers’ claim has been unequivocal; “We cannot and will not abandon our waterfront,” he declared, announcing his administration’s plan to follow the traditional strategy of the Army Corps of Engineers for shoring up by using protective bulwarks like flood walls, breakwaters, levees, sand dunes, and double-dunes. It remains to be seen whether his successor will follow through on this plan. The Corps’ model of beach and wall restoration, leaning heavily on federal funding and, associated more and more in the public mind with the protection of privileged beachfront homeowners, has come under harsh scrutiny. Whatever the outcome, the future of Zone A is not just a choice about how to respond to rising seas (a debate that is relevant to vulnerable coastal communities all over the world). The decision to develop or retreat will also reflect how longstanding patterns of environmental injustice continue to play out in different parts of the same city.

Hurricane Sandy had a rude impact on how we think about urban sustainability. For some, the storm’s urgent showcasing of climate-driven damage suggested that the window for sustainability is over. They have concluded, and not unreasonably, that there is insufficient political will to avert drastic climate change by reducing emissions. Instead, they have more fully embraced the mindset of adaptive resilience– a survivor’s mentality. Adaptive resilience is all about weathering the worst assaults, in the case of storms, through building hard-walled fortifications, or “softer” shorelines edges. Focusing on the immediate physical defense of communities inevitably invites us to think of them more as exclusion zones than, say, as safe harbors for climate migrants. Prioritizing this view feeds into the “lifeboat ethic” scenario popularized by Garret Hardin in the 1970s, which tried to rationalize how, in a world of limited or diminishing resources, the affluent in the North could ill-afford to take on board the world’s impoverished peoples. Giving priority to the protection of resource islands is a far cry from the course of action that rich cities could follow if they really were responding to the challenge of climate justice–they could cut emissions, for example, to allow less affluent cities to use their carbon allotment to develop out of poverty, or they could levy carbon taxes to pay for the humane resettlement of climate migrants.

Up until now, climate justice claims have been made through the nation-state framework of the UNFCCC treaty-making process. But this framework for distributive justice has proven to be frustrating at best. Could cities do better? More progress in climate policymaking has been made at the urban level than at the state or national level. One of the reasons for this is that City Hall does not usually make policy about energy generation and therefore is not subject to fierce lobbying from the fossil fuel industry. Urban politicians may have little sway over the biggest polluters, but they have made greater strides than their federal counterparts in energy conservation, emission mitigation, and zero-carbon alternatives in transportation and consumption. Could they help cities lead the way in recognizing and repaying climate debts to urban creditors in the South? How can non-state actors and communities self-organize with those goals in mind, given that urban managers tend to neglect social divisions within their own bailiwick, responding best to the interests of the well heeled?

Top image courtesy of nyc.gov