Nearly a year after Hurricane Sandy struck New York City, housing-related problems persist even in areas where repairs and rebuilding have taken place. The signs of ongoing crisis are often hard to see: mold grows underneath hastily replaced flooring and drywall, damaged homes go into foreclosure as displaced owners struggle to pay rent elsewhere, and residents begin to experience symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). While the latter example may not immediately appear to be a housing-related problem, research on the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Sandy reveals a complex relationship between housing damage and emotional distress. Visible housing damage not only augments distress, but also provides a way to articulate and make sense of that distress, as images and narratives of material loss enable affected residents to describe less tangible emotional experiences of disaster and recovery.

I. Housing Damage and Distress in Post-Katrina New Orleans

Home damage is known to lead to emotional distress (Ursano et al. 2008) yet it was not until recently that researchers began to understand the complexity of this relationship in disaster-impacted communities. One might assume that as the amount of housing damage increases, so too does the emotional distress of its owner or occupant. In post-Katrina New Orleans, however, Merdjanoff (2013) found that residents whose homes were badly damaged but remained standing had higher levels of emotional distress than those whose homes were completely destroyed. There are several possible explanations for such findings. For these residents, the ability to see but not occupy their homes seemed to prove more traumatic than its utter physical erasure, and possibly prevented closure. Those whose homes were severely damaged rather than destroyed were not immediately forced to leave memories behind and settle in new homes and neighborhoods. Instead, they may have had to decide whether to renovate or raze a severely damaged home, possibly encountering more difficulty attempting to recoup insurance benefits than had their homes been completely destroyed. They also dealt with the stressful emotional work of sifting through personal belongings like pictures, clothing, and furniture, deciding what to salvage or discard. In each of these scenarios, the emotional and physical energy needed to cope with a partially standing house can outweigh the energy needed to deal with its absence. As these were preliminary findings, Merdjanoff (2013) called for such possible explanations to be further examined in future research. With over 300,000 housing units in New York damaged and tens of thousands of residents displaced from their homes, Hurricane Sandy provides the next case for researchers to further explore the complex interplay between housing damage and emotional distress.

Midland Avenue, Staten Island, nearly ten months after Superstorm Sandy.

Photograph by Liz Koslov, 15 Aug 2013.

II. Emotions of Rebuilding in Post-Sandy Staten Island

In post-Sandy Staten Island, affected residents are dealing simultaneously with material losses and emotional trauma. Interviews and fieldwork suggest that these two experiences are intertwined in various ways. Margaret*, a Crescent Beach resident for twenty years, summed up her uncertainty, anxiety, and sense of vulnerability post-Sandy through a story about her difficulty replacing furniture lost in the storm. After watching the Sanitation Department crush her sofa, along with an irreplaceable antique cabinet from her parents, into a dumpster, Margaret realized that the aid money she received would not be sufficient to replace her possessions. When she went to buy a new sofa, she described spending nearly two hours in the store, unable to make a decision. Finally, she apologized to the salesperson for taking up so much time and left without making a purchase. Since Sandy, Margaret said she constantly feels “in two minds,” vacillating between fleeting excitement at the thought of new things and moments “when reality hits” and she realizes she could lose it all again. Describing her indecisiveness about rebuilding as a symptom of PTSD, Margaret believes she will only feel “at peace” if the government agrees to buy out her damaged home and thus enables her to move somewhere she will not feel so at risk.

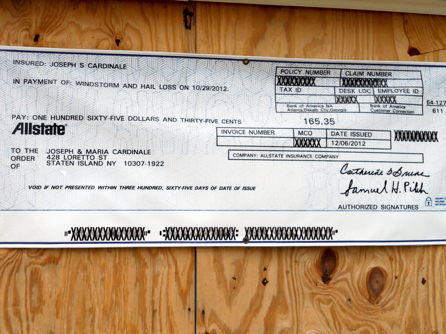

While Margaret draws on her material losses and ambivalence about rebuilding to illustrate the emotional turmoil she is experiencing, Maria and Joe Cardinale in Tottenville have made use of their house in a more explicit way to relate their feelings post-Sandy (Stein). Returning to their home after the storm, they discovered the storm surge had entered one side of the house, shifting it off its foundations and washing all the furniture into the remains of the living room. The house is structurally unsound and will have to be demolished, but the initial insurance payment came to less than two hundred dollars. Angry, they posted a banner sarcastically thanking their insurance company for the help, as well as an enlarged image of the check they received, on the side of their damaged home.

A sign on a red-tagged house in Tottenville, Staten Island, reads “Thank You, Allstate Homeowners Insurance. Approved for $165.35 in damages. ‘We are in good hands’!!”

Photograph by Liz Koslov, 6 Jun 2013.

Photograph by Liz Koslov, 6 Jun 2013.

As residents continue to await insurance payments, government buyouts, demolition permits, and aid for rebuilding, many areas across the South and East Shores of Staten Island still look much the same as they did shortly after the storm, with piles of broken furniture and building materials sitting alongside partially-collapsed houses. In some places, though, the damage is less immediately apparent. In Midland Beach nearly eleven months after the storm, Barry* opened the door of his seemingly intact home to reveal its gutted interior. Surrounding houses, he emphasized, also look fine on the outside but remain completely devastated within. Describing his ongoing wait for rebuilding assistance, and his uncertainty over elevation requirements and new flood insurance rates, he begins to blink rapidly and grows quiet. Regaining his composure, he closes the door of his damaged house, gets in the car, and slowly drives away.

III. Conclusion: The Visual Culture of Lingering Crisis

Nearly six months after Hurricane Sandy, advertisements began appearing on subways, bus stops, and scrolling across the electronic displays that ring the Staten Island ferry terminal. In the “Stress Still Lingers” campaign, the tagline acknowledges that mental health complications can persist long after a disaster like Sandy makes landfall. Still, by depicting a sole person or small family, the campaign also works to frame emotional distress as a problem faced – and resolvable – by individuals, so long as they choose to seek help. The seemingly personal experience of emotional trauma, or the loss of one’s home, belies broader patterns of social and environmental vulnerability. To represent these enduring forms of crisis is to confront a comparable challenge to representing the crisis of climate change more broadly. Each possesses a long timeline that conflicts with the way disasters are typically recognized and made legible. They are difficult to visualize, and necessitate complex accounts of causality. It is easy to miss the larger pattern of destruction that underlies and sustains them.

Bus stop on Midland Avenue, Staten Island. Photograph by Liz Koslov, 15 Aug 2013.

In the post-disaster settings of New Orleans and Staten Island, housing and mental health are intimately related. It is difficult to foresee how recovery and resilience will be achieved without recognizing this complex interdependence. Mental health counseling for residents who remain displaced, at risk of foreclosure, or are suffering health effects from mold exposure can only be part of the solution. Decisions whether to seek buyouts or rebuilding assistance are inseparable from feelings of fear, hope, and uncertainty. An individual’s mental health, like a family’s home, can provide a limiting frame for action, focusing attention on personal, private experiences and obscuring the connections between them. In order for our cities to become more resilient we must cease viewing housing damage and emotional distress as individual burdens, and instead seek ways to envision and construct a collective way out of the crises we confront together.

Faint writing underneath reads, “Sandy may have destroyed our homes, but not our spirit!”

Photograph by Liz Koslov, 15 Aug 2013.

*Name has been changed

Interviews for this project were conducted as part of the Superstorm Research Lab, a mutual aid research collective. For more information, see www.superstormresearchlab.org.

Top image: Damaged house in Midland Beach, Staten Island. Photograph by Liz Koslov, 15 Aug 2013.

References

Merdjanoff, A.A. 2013. “There’s no place like home: Examining the emotional consequences of Hurricane Katrina on the displaced residents of New Orleans.” Social Science Research 42: 1222-1235.

Stein, M. D. 2012. “Staten Island couple’s barb, directed at Allstate, takes Facebook by storm.” Staten Island Advance. Retrieved from <http://www.silive.com/southshore/index.ssf/2012/12/staten_island_couples_barb_dir.html>

Ursano, R.J., Fullerton, C.S., Terhakopian, A. 2008. “Disasters and health: distress, disorders, and disaster behaviors in communities, neighborhoods, and nations.” Social Research 75: 1015–1028.