Hong Kong cinema has been in a state of ambivalence for a long time despite the fact that it has always been so unambivalently commercialized. This is less a cause than a consequence of the fissured condition of cultural production shaped by what I call the “double hegemony” of the national and the colonial.[i] Coloniality, as Walter Mignolo has argued, can exist without colonialism; in the case of Hong Kong, coloniality is both the consequence of British colonialism (which presumably “ended” in 1997) and a system of values and public governance–a variation of the “colonial matrix of power”–perpetuated in the nationalized present, under “one country, two systems.”

“Decolonial moments” in Hong Kong cinema, therefore, have to be sought through the fissures of the dual paradigms of the national and the colonial. As far as the Hong Kong film industry is concerned, the dual paradigms are translated into the forking paths of national integration and globalization. These circumstances are not favorable to the development of “decolonial aestheSis” as a coherent, vocal, and sustainable critical practice. Being at a disadvantage, however, does not prevent individual filmmakers from exploring the dilemmas, conflicts, and tensions of a compromised condition of existence. Decolonial moments therefore are understood as a scene, image, dialogue, or film mobilized by a new or deviant subjectivity that lays bare and critiques the ideological fallacies of the prevailing political regime. In the following I first map out the terrain of cultural politics in Hong Kong since the 1980s, then discuss certain key moments when a decolonial subjectivity is thematized or visualized through the cinematic medium.

Unpacking Coloniality in Post-Handover Hong Kong: Double Hegemony and Hybrid Universals

The 1980s was a time when a widespread crisis consciousness prompted the historical awakening of a “Hong Kong subjectivity” in the city’s cultural imagination, as it looked to the coming of 1997. In the post-1997 era, public challenges to the legitimacy and efficacy of “one country, two systems” have been escalating since the 500,000-strong mass protest on July 1, 2003. 2012 marked the fifteenth anniversary of the “Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.” On that day, alongside official celebrations of the reunification, and despite tightening police surveillance and crowd control restrictions, over 400,000 civilians (out of a population of seven million) marched through the streets of the Hong Kong island in opposition to the undemocratically elected new Chief Executive, C. Y. Leung, and his scandal-stricken cabinet. No doubt these protests were fueled by growing public discontent with the current regime, rather than its colonial predecessor. However, a closer look at the central controversies and their historical roots shows that the 1997 “handover” swore in the national government as the legitimate heir of the colonial apparatuses (built primarily for trade and commerce by imperial design[ii]) left behind by the British, and that the heir has learned to utilize that colonial inheritance in the new guise of “socialist capitalism,” a crossbreed of the two most influential Western paradigms of modernity. In this light, Hong Kong’s collective plight is the result of historical processes that culminated in the historic convergence of socialism and capitalism in China, which for the past 150 years has been a testing ground for various modernity projects. In the “postcolonial” present, Hong Kong’s colonial modernity, designed for trade and commerce, is given a new name by Deng Xiaoping, ex- Chairman of the People’s Republic of China: “prosperity and stability.” Fifteen years down the road, however, the majority of locals have come to realize that those promises are reserved only for the privileged minority at the expense of broader democratic rights and social equality for all. Coloniality, thus, has to be understood as an omnipresence under the double hegemony of the colonial and the national, which in this specific application are not distinct entities but a hybrid of two universals that constitute the “matrix of (centralized state) power” of the Chinese nation-state. Unpacking the “colonial” in the national present is therefore a first step toward decolonial thinking and cultural practices in the context of Hong Kong. The following discussion is organized into three interrelated themes: decolonializing the nation, decolonializing the city, and decolonializing the image. These are not self-contained categories but are mutually constitutive and inter-referential.

Decolonializing the Nation

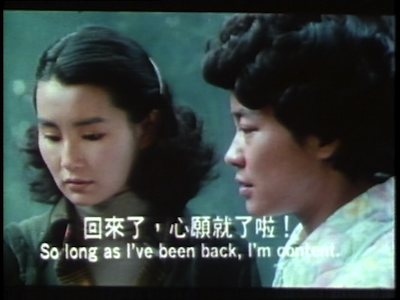

Among the Hong Kong New Wave directors,[iii] Ann Hui is one of the most committed to a cinema of “social significance.” Her 1990 feature, Song of the Exile, posits “exile” as a shared predicament of the main characters who span three generations of a family. Their transnational trajectories since World War II straddle different historical time-spaces: China, Britain, Hong Kong, Macau, and Japan. As Hamid Naficy argues, while exile in the contemporary world involves “different modalities of displacement,” very often it is the “frustrating elusiveness of return that makes it magically potent.”[iv] In the film, exile is less about forced displacement than a self-imposed state of being resulting from conflicted personal and national/colonial memories. In Song, the burden of national histories is visualized in two crippled figures: an ex-Kamikaze fighter who is still fighting a war within, and a Chinese scholar and nationalist tortured by the Red Guards for possessing Chinese literary classics during the Cultural Revolution. Aiko, one of the two female protagonists, is the daughter-in-law of the Chinese nationalist and elder sister of the ex-Kamikaze, and begrudged by both as a “traitor” and “national enemy.” Hueyin, Aiko’s daughter who studied journalism in London, returns to Hong Kong disillusioned when she realizes that, after losing hope of becoming a BBC journalist, she will never be accepted as an “equal” in Britain. Through the two leading female characters and the transnational social network around them, the film maps out a geocultural terrain within which the overlapping histories of Japanese imperialism, Chinese nationalism, and British colonialism are encapsulated in the trajectories of a migrant family in Hong Kong. By situating Hong Kong’s “identity crisis” within this broader historical and geopolitical frame, Hui’s film disrupts the coherence of cultural/self-identity in the exclusionary politics of the nation-state–whether British or Chinese. The real and symbolic journeys of the two women, being “colonial subjects” in their own ways, bring about the awakening of individual agency and open up a space-in-motion from where a decolonial subjectivity emerges.

In the film, “nation” not only refers to “China” but is also a frame of reference in which “nationhood” is conflated with “statehood.” This conflation of terms confines identity to the ideological prerogatives of the state. The convoluted linkages between nation, state, and the (post)colonial city are also found in the work of Vincent Chui, a younger independent filmmaker and Hui’s co-director in an earlier documentary film, As Time Goes By (1998). Due to limited space I will focus on Chui’s decolonial vision of postcolonial Hong Kong in his latest feature, Three Narrow Gates (2008). Utilizing Chui’s favorite three-storyline structure, this film is a crossover of social realist cinema and generic codes of detective and thriller films. The three stories are interwoven to yield a disturbing vision of institutional violence and corruption in post-handover Hong Kong: a woman journalist’s investigation into a corporate corruption scandal brings her into contact with an ex-cop and a reverend-cum-political activist. The trio is joined by another cop who defies his supervisor’s order to suspend an investigation into a murder purportedly connected to the scandal. The cat-and-mouse chases become more lethal as the group gets closer to the truth. Symbolically, the three main characters are dissidents of three orders of social-political power: the church, the police, and the mass media. They are ostracized from their own kind when they refuse to corroborate. As the narrative unfolds, a much bleaker vision of Hong Kong under “one country, two systems” emerges: the murders and violence are orchestrated by an invisible, and almost invincible, conglomerate of transborder corporations and government authorities in Hong Kong and China. Thanks to a guerilla-like subversion of Internet surveillance, the group wins a small victory in the end by exposing the crimes in cyberspace. This “happy ending” might be a consolation to the audience, but the lingering phantom of institutional(ized) violence and corruption precludes an optimistic reading. Chui’s film, while not a box-office success, was selected in 2012 for a special screening in commemoration of the June 4th Tiananmen Incident, together with his earlier work, Leaving in Sorrow (2001). The significance of Three Narrow Gates lies in its undaunted pursuit of an independent vision that questions the meaning of “reunification” and “decolonization,” hence the nature–and desirability– of “stability and prosperity” as a political prerogative.

Decolonializing the City: Fruit Chan

As a key figure of post-New Wave realist cinema, Fruit Chan is both a representative figure and an anomaly: his “Hong Kong Trilogy”[v] is reputed for its portrayal of the complex social and political realities of Hong Kong during the political transition. Chan’s other films, such as Public Toilet (2002) and Hollywood, Hong Kong (2001), exhibit a tendency toward fantasy that recalls his commercial projects. Like many New Wave directors, Chan is interested in exploring the psychosocial dynamics of urban life. Among his favorite characters are working class youths, prostitutes, migrant workers, ethnic minorities, and illegal immigrants from mainland China. Migration and migrancy are common motifs in Chan’s films: Little Cheung (1999), Durian Durian (2000), and Hollywood, Hong Kong feature mainland women traversing the boundaries between Hong Kong and China. Whether as illegal workers or prostitutes on a return visa, Chan’s mainland women characters command a depth of character that is only incrementally revealed in the storytelling. This strategy puts the audience at a disadvantage: it invokes stereotypical images and assumptions about mainland women that saturate the local mass media only to orchestrate a reversal of meaning in the end. A recurrent thematic concern in Chan’s films is the internal social/cultural/political boundaries that have led to misperceptions and misrecognitions of sorts between locals and nonlocals, as well as between different social classes. Chan’s Hong Kong therefore is never the affluent, cosmopolitan city celebrated in official and mainstream media, but an internally fractured and disjunctive social space that reminds us of Pheng Cheah’s critique of neoliberal cosmopolitanism and what she calls the “uneven force field” of the “cosmopolitical,” that is, “a material global condition that . . . has not yet generated a mass-based cosmopolitan consciousness.”[vi]

In Chan’s filmic universe the (post)colonial city is subject to multiple dislocations and relocations through the centrifugal and centripetal forces of migration. In Hollywood, Hong Kong the city is schizophrenically divided between social classes and disjunctive urban spaces. The social immobility of the locals, symbolized by their spatial immobility, is juxtaposed with the figure of a scheming mainland woman, who outsmarts three foolhardy Hong Kong working-class males in a series of grotesquely erotic encounters and finally embarks on her dream journey to Hollywood. As a metonymic sign of the “global space,” Hollywood is given a most clichéd, one-shot appearance at the end, but the purpose of the woman’s journey remains unexplained. As a result, “Hollywood (US)” becomes a “non-place,” a virtual sign that stands in for the lure of the capitalist West to a “Third World subject.” Interestingly, “Hollywood (Plaza)” is the name of an actual place–a middle-class housing estate in Hong Kong, towering over a soon-to-be-demolished squatter neighborhood, the primary setting of the film. Hollywood, Hong Kong compactly echoes Chan’s other films that portray Hong Kong as a British colony built in the image/shadow of a Western metropolis, only to be left behind by both the colonizer and the motherland, each in pursuit of their respective globalizing dreams.

Decolonializing the Image: Wong Kar-wai

Much has been written about Wong Kar-wai, but as Hong Kong’s homegrown post-New Wave (or “second wave”) auteur, Wong’s intervention into what Ackbar Abbas calls “the practice of the image”[vii] deserves a place in this report on decolonial aestheSis. The following, therefore, is more a reframing of Wong through the schism of the decolonial.

Wong’s unconventional film style made an initial impact on the local gangster film genre when his first feature, As Tears Go By, was released in 1988. His subsequent projects show an increasing tendency toward genre subversion. Wong’s interest in reworking and deconstructing genre goes side by side with his aesthetic-philosophical reflections on time, memory, and history. One of Wong’s favorite visual tactics is slow motion, which is used not to obtain clearer images of action but to problematize and disturb the perception of speed and movement. To Abbas, Wong is the director par excellence in Hong Kong cinema’s aesthetics of “dis-appearance,” or “deja disparu,” which he compares to Walter Benjamin’s Paris of “love at last sight.”[viii] The overall effect is not the acceleration of action and speed but a breakdown of the image into blurry fragments. Wong’s distortion of motion and the deconstruction of speed, in the context of Hong Kong (cinema), is indeed a decolonial strategy, in the sense that the image in Wong’s film is a critical practice through which any coherent vision of the cosmopolitan city breaks down into images of inconstancy and affective disconnection. Wong’s strategy of decolonializing the image is manifest in his treatment of time, memory, and nostalgia. While nostalgia is known to be an important component of Wong’s cinematic imagination from Days of Being Wild (1990) to In the Mood for Love (2000) and 2046 (2004), I have elsewhere argued that Wong’s use of nostalgia has a self-reflexive and ironic edge that subtly undercuts the conservative logic of nostalgia.[ix] In these films, nostalgia speaks through a mise-en-scene saturated by objects that evoke the “mood” of a bygone era (the 1960s). Upon closer examination, these objects–including the characters’ body movements and their meticulously designed costumes–are so emphatically nostalgic that the image looks emphatically aestheticized, to the extent that the verisimilitude of the meticulously reconstructed nostalgic world begins to dematerialize into a visual effect. Some critics attribute Wong’s self-conscious artificiality to postmodernist aesthetics, but Wong’s penchant for exhausting the signifying potential of the image invites a more context-specific decoding.

In the “1960s trilogy,” Wong’s deconstruction of nostalgia culminates in the last installment, 2046. In this film, Wong, rather uncustomarily, employs a political pun right from the naming of the film: “2046” refers, firstly, to a hotel room number that reminds us of the story of the lovelorn lovers in the prequel, In the Mood for Love, and secondly to a place where one can recover lost memories, as “2046” is the imaginary destination of a transgalactic express train in a science fiction story written by the protagonist, Chow Mo-wan. Extratextually, 2046 is the year that marks the end of ex-Chinese Communist Party Chairman Deng Xiaoping’s political promise to Hong Kong people: the colonial city’s capitalistic “way of life” will “remain unchanged for fifty years” after 1997. In the film, “2046” is a destination from where no traveler has ever returned. (One is reminded here of Hamlet’s discourse with death–the ultimate “destiny” unknown to and unknowable by the living.) Metaphorically, such (inter)textual play exhausts the logic of such a promise: to remain “unchanged” for 50 years is to live in “changeless time.”[x] “2046,” in this sense, is an impossible destination, a mythic future stasis. In the film, “2046” is more about the past than the future: Chow Mo-wan’s bitter memories of lost love are projected into a fictional realm where the past becomes an enigma hidden in an unknown future. “2046” therefore is an overdetermined signifier, and the circularity of its signification leads to, not surprisingly, nowhere–or nowhere other than where one started. The intensification of this circularity as the film/train progresses toward “nowhere” playfully subverts the linear logic of progressive time so deeply embedded in colonial modernity, and so fervently embraced by the nation-state in the present.

Throughout the trilogy Wong repeatedly invokes other locations outside Hong Kong in the form of a historical footnote. In Days of Being Wild, the main character, a handsome playboy, goes to the Philippines and ends his life there when his biological mother refuses to grant him even a single meeting. In Mood and 2046, the Chinese diaspora in Singapore invokes a translocal, regional space of migration that also bears the imprint of Western imperialism. Toward the end of Mood Chow Mo-wan is seen depositing his memories into a wall-hole amidst the ruins of Angkor Wat. The film’s spatial extension to other colonial spaces in Asia is only weakly driven by narrative necessity; the juxtaposition of these sites therefore works more to resituate Hong Kong’s colonial history, hence its postcolonial present, within the larger historical frame of Euro-American imperialism in Asia and its contemporary ramifications. If 2046 is a haunting tale about the end of an era that propels the historical subject into “changeless time,” hence the obsession with a past that dematerializes into visual effect, the film also invites the viewer to see beyond predetermined colonial and national time-spaces in order to envision and connect to other memories and images. If nostalgia is a mode of postmodern “consumption” of history and a form of escapism, the exhaustion of the nostalgic in Wong’s films points toward the exhaustion of historical agency in nostalgia. For any future imagination to be feasible, that is, for “changeless time” to be undone, the true implication of the past has to be salvaged from its nostalgic aura and recast in the complex ambivalences of the present.