In a sea of colorful placards, the blanket-stitched banners of Amihan National Federation of Peasant Women seem comforting. It personally reminds me of what Alexandra Kollontai calls “our grandmother’s time”–what family looked like before capitalism: “The woman did everything that the modern working and peasant woman has to do, but besides this cooking, washing, cleaning and mending, she spun wool and linen, wove clothing and garments, knitted stockings, made lace … and manufactured her own candles.” These activities, according to Jodi Dean, were necessary not just for the family but the state as a whole. The national economy benefited from the products that the women made for the neighboring market.

As an act of resistance against the marking of the anniversary of Republic Act 11203 an act liberalizing the importation, exportation and trading of rice in the Philippines, we asked the chairperson of Amihan to facilitate a stitching workshop. We called it Letter-Patching Workshop versus Rice Liberalization. Participants gathered in a quaint zine library in Cubao—scissors, needles, and fabric in hand.

Zenaida Soriano, who we fondly call Ka Zen, began the workshop by sharing that sewing has become her outlet. When not delivering protest speeches or organizing peasant women, she hand-stitches banners to release her anger against the ineptitude of the government. Even during her time off, she transforms her anger into sustainable banners, into propaganda work.

First, the edges of the cheesecloth or the katsa must be sewn. This is the only time Ka Zen uses the sewing machine. Of course, the katsa must also be washed, as one usually buys them in the local bakeshop. Katsa is often used as a flour sack, usually sold for P5.00 with dried flour still sticking to the fabric.

Senator Cynthia Villar is one of the proponents of the Republic Act 11203, or the Rice Liberalization Law. Cynthia is the wife of Manny Villar, the richest Filipino according to Forbes’ World’s Billionaire 2021 List. The pair are landed elites who have converted vast agricultural lands into subdivisions, commercial spaces, and malls.

Filipino rice farmers are opposing the Republic Act 11203 and are calling for its repeal based on the following important points:

1. Prior to its enactment, the farmers were already enduring chronic crisis and poverty, thus, they were facing unrecoverable debts, leading to their displacement from lands and to termination of rice production for the Filipino population.

Last October 2020, farm gate prices of palay plummeted and bankruptcy of rice farmers became imminent: P10 to P14 per kilo in Nueva Ecija, Isabela, Tarlac, Bulacan, Pangasinan, Mindoro, Ilocos Sur ,and Bicol; the same in Negros Occidental, Capiz, and Antique; at P11 to P15 per kilo in Agusan del Sur, Davao del Oro, Davao del Norte, South Cotabato, North Cotabato, Lanao del Norte, and Caraga.

2. Filipino rice farmers lost at least P75 billion due to the implementation of the RA 11203. The value of palay in 2018 was at P20.19 per kilo, but this drastically fell to P16.22 per kilo in 2019. Thus, by applying the decline to the little more than 18.8 million metric tons volume of production of 2019, it amounted to P74.8 billion, which was the lost potential income of rice farmers that year.

3. The RA 11203 did not serve the welfare of both poor producers and consumers. It led to the bankruptcy and indebtedness of rice farmers, while retail prices remain unaffordable to poor consumer families who have low purchase power and household incomes.

Harassment and attacks

After measuring, cutting the cheese cloth, and sewing its edges, we began cutting the letters. We were to cut the letters: JUNK RICE LIBERALIZATION LAW from scraps of fabric. Around twenty participants gathered around tables and sat on the floor, cutting letters and sewing them onto the katsa. We sat next to each other, needle and thread in hand. The room fell quiet as Nanay Zen continued to tell us the conditions of the Filipino peasant women:

When we think of the word farmer, for Filipinos at least, we immediately picture a man with his carabao (farming remains backward and small-scale because of the semi-feudal system). The majority of the women in the countryside, however, are farmers and agricultural workers. They are at the forefront of agricultural production—farming, fishing, and working in rubber, pineapple, banana, palm oil plantations. As farmers, they are involved in the preparation of land, removing weeds, planting, the long process of tilling that involves spraying pesticides and fertilizers, harvesting, drying, transporting the produce to the local market. Some of the women farmers even sell their crops themselves.

According to Amihan, seven out of ten farmers remain landless and women suffer greatly because of this. The country remains agricultural and agrarian but the lands are monopolized by the rich and elite hacienderos and compradors (local partners of foreign investors).

In Hacienda Yulo, amid pandemic, attacks on land rights and livelihood continue. Last August 24, 2020, a contingent of armed goons brandished their Armalite rifles at a group of peasant women, including the elderly, who blocked them from entering their community. The goons were hired by Yulo-Ayalas to wipe out the farmer communities living in the area that was to be converted into a country club and golf course. “Our place used to be a paradise. Now, after they have burned down our house and demolished the houses in our community, it’s nothing but hell,” says Nanay Idang. She is one of the farmers whose parents and ancestors have been tilling the land. She has proof that her parents have been paying taxes. Her normal voice has not returned after enduring multiple instances of harassment from armed goons. As she narrates her experience, her voice trembles, as if she’s always about to cry.

Haciendas and agricultural lands controlled by local landlords and foreign investors are converted into commercial spaces under President Duterte’s Build-Build-Build program. The farmers cannot seek help from the local police and their mayor because they, too, protect the Yulo-Ayalas, landlords who own hundreds and thousands of farms in the country.

Despite the series of threats, peasant women and mothers in Sitio Bangyas tell us, “Buo ang loob namin. Magkakapit-bisig kami para hindi sila makapasok” (“We are firm in our stand. We will create a human barricade so the armed goons cannot enter”). Peasant organizations led by women have always protected their communities. “It has to be the women, the elderly women. Because if our husbands face these armed goons, their rage will lead to physical fight. Magkakasakitan,” one of the younger mothers shared. In a video recording of this encounter, you will see the mothers of Sitio Bangyas talking to a masked man. He holds his rifle at gun point as the women walk up to him, using their bare hands to push the long gun away.

Discrimination Against Peasant Women

Ka Zen taught us how to do the blanket stitch. This stitch secures the letters and protects it from ripping and tearing. First, one has to do a running stitch so the letters will not move. The participants were surprised that we needed to do a running stitch of all twenty-five letters first. We wanted to try the blanket stitch right away! After a few hours of collective stitching, we were unable to complete the banner. We decided to pass the banner from one volunteer to the next until the day of the protest. We unfurled the statement on February 14, 2020 during a protest marking the first anniversary of RA 11203.

Aside from calling for the junking of the Rice Liberalization Law, peasant organizations and members of Rural Women Advocates resist the high cost of production. In some provinces, farmers have to come up with P50,000 to P70,000 for land rent, seeds, fertilizers, irrigation, rental of farm equipment, transportation, etc. Because of RA 11203, the price of palay, or rice crop, plummeted to P10 per kilo! Farmers have to enter onerous contracts and be buried in debt in order to till the land, but their crops are bought at very low prices. Hence, peasant women are victims of exploitation, slave-like wages, and abuse.

On top of the multiple burdens that they carry doing farm work and housework, wives often look for odd jobs in order to pay for their debts. They work as labandera (laundry workers), housekeepers, and vendors.

On top of the multiple burden, women also suffer from discrimination. A survey from the Philippine Statistics Authority revealed that in 2019, the average daily nominal wage rate of male and female agricultural workers was P335 and P305.60 per day, respectively. The wage differential is around P30.00 per day. Hence, farmer organizations play an important role in pushing for just working conditions, equal pay, and minimum wages.

Women farmers rise above the dire situation when they are organized. Amihan has chapters in Isabela, Bicol, Cavite, Cagayan, and different provinces. Aside from this, women farmers also hold leadership positions in their organization. They act as chairs, lead the legal battles to defend their land, educate their fellow farmers, and mobilize their members to hold peaceful protests. However, according to the Amihan National Federation of Peasant Women, the state silences peasant women leaders. “Adelaida Macusang, jailed in Tagum City, died due to cardiac arrest and kidney failure; Nona Espinosa, jailed in Guihulngan City, was separated from her newborn baby Carlen who died due to infection of lungs; Ma. Lindy Perocho, jailed in Escalante City, 57, a member of the National Federation of Sugar Workers accused of illegal possession of firearms and explosives.”

Defend Peasant Women Campaign

On March 21, 2021, a series of crackdowns killed farmers, advocates, and activists. We called it the Bloody Sunday Massacre because nine activists were killed. One was Dandy Miguel, president of Pamantik-Kilusang Mayo Uno, a trade union in Southern Tagalog. He was shot eight times on his way home. That same day, five activists and organizers in Laguna were arrested based on trumped up charges. Two fisherfolk were murdered in front of their nine-year-old child in Batangas. They were Chai and Ariel Evangelista of Ugnayan ng Mamamayan Laban sa Pagwawasak ng Kalikasan at Kalupaan (UMALPAS KA). Their son hid under the bed. Emmanuel “Manny” Asuncion of Bayan-Cavite was also gunned down. Randy and Puroy Dela Cruz, both of the Dumagat Indigenous people, were also killed. Also slain in Rizal province were Melvin Dasigao, Mark Lee Bacasno, Abner Esto, and Edward Esto.

Two days before the raid, President Rodrigo Duterte announced, “I’ve told the military and the police, if they find themselves in an encounter with the communist rebels and you see them armed, kill them, don’t mind human rights.” Of course, the activists were not armed, nor were they communist rebels. They were part of legal organizations.

Defend Southern Tagalog was launched. This was the time I began deconstructing thrifted clothes and turning them into “protest wear.” I simply stitched scraps of fabric on to jumpers and skirts and painted our calls. We needed to gather donations for the burial of Puroy and Randy Dela Cruz, which cost around P230,000. We also accepted donations for legal assistance and bail funds for the Laguna5.

Along with Defend Southern Tagalog, Defend Peasant Women was also launched. Peasant women have increasingly become targets of human rights abuses through the Anti-Terror Law and President Rodrigo Duterte’s counter-insurgency policies, like Memorandum Order 32 and Executive Order 70, or the whole-of-national approach which created the infamous National Task Force to End Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC). Amid surging COVID-19 cases, the Duterte regime allocated billions of the nation’s budget to the armed forces and police over the health and socio-economic sector. The militaristic response included strict lockdowns and arrests. It became an excuse to attack progressive organizations, commit human rights abuses, and red-tag land rights advocates.

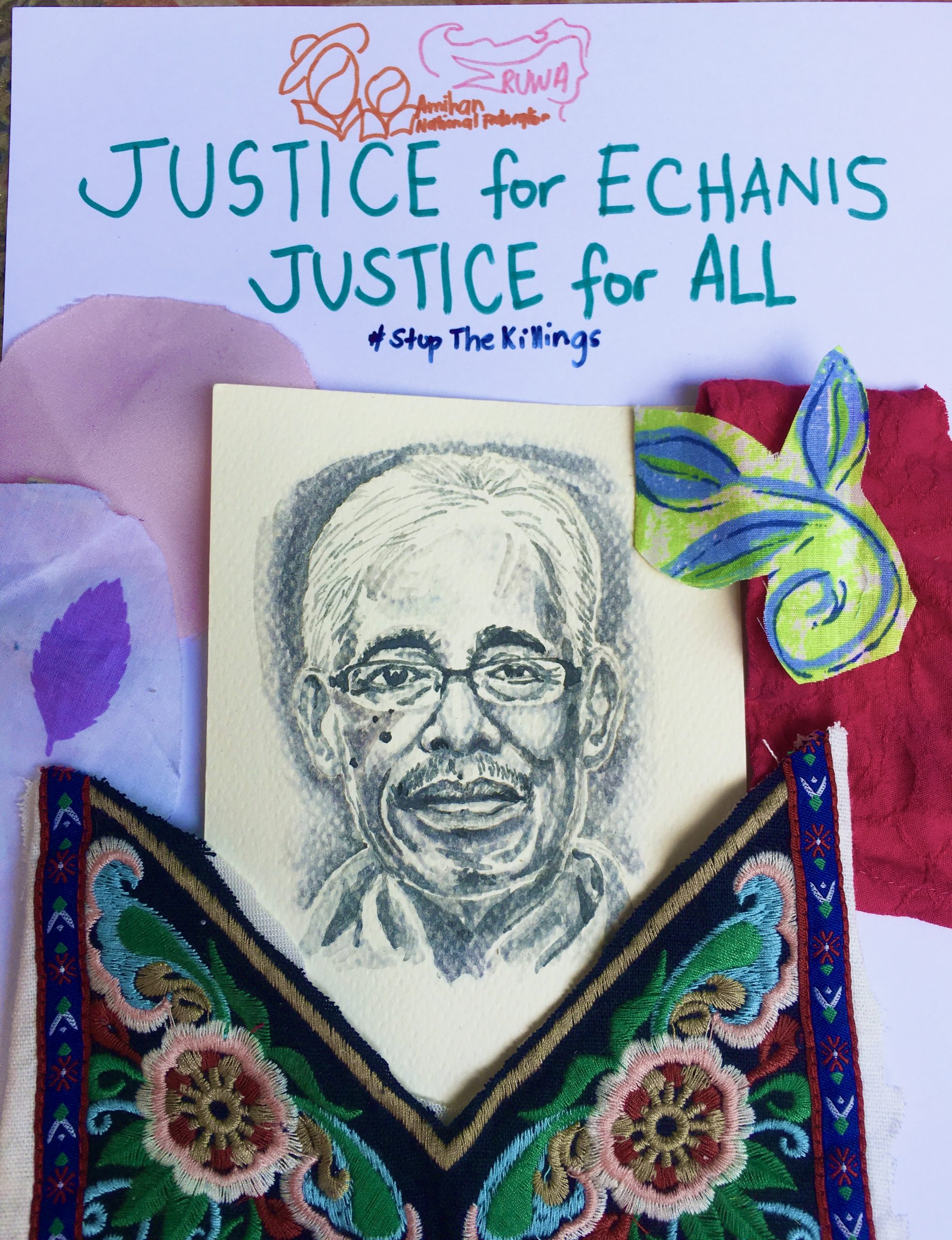

We painted the calls Duterte the Orphan Maker and Mothers Not Terrorists because the counter-insurgency policies have systematically used military, police, and paramilitary forced to victimize peasant women asserting their rights to land and livelihood. Elderly and sick peasant women political prisoners were denied proper medical attention, worsening prisoners’ health conditions and leading to the death of Adelaida Macusang. Alongside our handstitched banners, Zenaida Soriano proclaimed, “We call an end to the series of harassment, vilification and red-tagging of peasant women leaders, organizers and members under Amihan including Leonisa Taray of Bohol, Julie Marcos, Emelia Ventula, Jacqueline Ratin of Cagayan, Cita Managuelod, Rowena Hidalgo, Nenita Apricio and Gladys Ganado of Isabela and Jewelyn Fernandez and Jeralyn Cerezo of PAMALAKAYA-Aklan.”

Our needles and fabric scraps kept us together—the thrifted clothes became our canvas and banners. When the COVID-19 cases surged to a million, we were subjected to another series of strict lockdowns and curfews. We can turn only to stitching and painting to document the calls of peasant women. We could not travel and conduct fact-finding missions because we were prevented from even going outside our homes.

Along with our solidarity statements, social media rallies, webinars, and online fora, our crafts condemned the mass killings, illegal arrests, and detention. We punctured fabrics and crafted against the aerial bombings in farmer communities, against forcible mass evacuation, against the food blockade, and against the trump-up charges filed against peasant women who organized farmers.

We brought our protest clothing to rallies and gathered donations by selling them online. We collectively mended our grief in front of our cameras, stitching and processing our anger through our solidarity statement. Our bandanas, crocheted bags, embroidery, and arpilleras demanded accountability, called for justice, and archived the crimes of our fascist government. Still today, we continue to use our crafts to connect to those who are afraid to join the struggle. By conducting basic crochet workshops and comic-making workshops we find openings and lead discussions on the conditions of the peasant women. We tame our collective anxieties and traumas through our needles, hooks, and yarns so that we may continue the fight against exploitation and abuse and push for genuine agrarian reform.

Cover image: Members of Rural Women Advocates carry a hand-stitched banner with the call “Rural Women Resist! Oust Duterte” during International Working Women’s Day.