Three years ago, in the summer of 2010 I began a series of projects for Documenta 13 as part of the artists’ initiative called AND AND AND. On the one hand, these contributions focused on my Phantom Limbs and Twin Towers Go Global projects, creating a series that was spread out over multiple locations around the world between 2010 and 2012. These works happened both within and outside the official 100 days of Documenta itself. To complement these spread-out interventions, I co-organized, with Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri, a highly concentrated collective event entitled “Five Decolonial Days in Kassel: Transforming Our Realities.” Held at the platform’s Turnhalle space in Kassel, Germany, from July 11 through July 15, 2012, this series of walks, presentations, discussions, screenings, and workshops bridged questions of coloniality/modernity with the topics of the common(s), revocation, and noncapitalist life that were to be explored throughout the hundred-day duration of AND AND AND.

Following a presentation entitled “Beyond the Colonial Unconscious” by Suely Rolnik, the five-day exchange included Ayreen Anastas, Dalida María Benfield, Heath Bunting, Maribel Casas, Sebastian Cobarrubias, Teresa Díaz Nerio, Rene Gabri, Pedro Pablo Gomez,* Karen Hakobian, Brian Holmes, María Iñigo Clavo, Alanna Lockward, Walter Mignolo,* Raúl Moarquech Ferrera-Balanquet,* Tanja Ostojić, Claire Pentecost, Harout Simonian, Miguel Rojas-Sotelo,* Catherine Walsh,* and myself (*denotes long-distance contributions). The range of approaches and topics covered was broad, including epistemic disobedience (Mignolo), the politics of naming (Walsh), the mapping of migratory struggles (Casas and Cobarrubias), decolonial aesthetics (Balanquet, Gomez, and Rojas), Elinor Ostrom’s work on the commons (Benfield), as well as located and particular: blackness in Europe (Lockward), coloniality in Brazilian cinema (Iñigo Clavo), sans papiers in Germany (Ostojić), and the ongoing forms of racism in postcolonial and postrevolutionary Mexico (Nerio). On the fourth day, Benfield led a very rich workshop in which all those present contributed ideas for decolonial strategies, to be assembled in a shared archive. Throughout the five days we strived to create a commons that could in itself be decolonized by making room for truly global forms and philosophies of shared property and collective labor, including kilombos, ejidos, caracoles, comités de oriundos, and ayllú, to mention a few. The workshop countered the erasure of the specificity of these forms by some liberal and neo-Marxist discussions, as well as their continuous subsumption within US and European forms of the commons.

Our “Five Decolonial Days in Kassel” event focused on the transformation of reality through decolonial thought and action, an idea I have written about more extensively in the central essay of the recent book entitled Grand Gestures & (Im)modest Proposals, published as the concluding part of the works I produced for Documenta 13 AND AND AND. While transformation of reality is also a guiding principle for the following discussion, I have taken here a less essayistic approach in order to stress the role and methods of artists and nontextual producers within the decolonial option. This piece, then, is to be understood as a discourse led mostly by the images and should therefore not be read without them. Each image constitutes a part of the larger argument for a decolonial aesthetics. Adding the necessary context through a brief caption, I have also written a series of short decolonial propositions directly tied to the visual components. These decolonial image/caption/proposition triads are meant to stay together, but they can be rearranged as separate units into larger or smaller geometric assemblies, longer or shorter publications, as well as linear or nonlinear compositions. As we begin to address these images and artworks in relation to decolonial thought, it is key to remember that they are simply my own attempt to produce an aesthetic synthesis from over a decade of engaging these ideas through their visual and artistic practice. I am intentionally calling these triads propositions, so that their tone can be maintained between that of a question and a statement. If there is the sound of certainty in them, then it comes from the range of emotions of the voice that speaks them: conviction, love, passion, even anger. But any such certainty does not make this aesthetic synthesis into a manifesto. I have participated in the issuing of past decolonial statements, and manifestos, but these were all produced collectively. As an individual, I would never claim to speak for the powerful diversity of the decolonial movement. I am simply trying to add a visual and artistic voice to its conversations.

Note: All images included are by Pedro Lasch. In the case of collaborations, the collaborators are listed in the corresponding caption. The brief nature of this piece does not allow lengthy explication. These propositions, captions, and descriptions are meant to provide only the most essential context and point to relevant directions. Extensive writings and materials exist on many of these works, and many of them are available in English and Spanish at http://www.pedrolasch.com

The word “aesthetics” is reinvented by decolonial movements as a critique of the repressive mechanisms of colonial “beauty” associated with this term. It is a concept worth reforming, as it also points to the emancipation of experience, the body, and the senses, and all of these are central concerns of the decolonial struggle.

Image 1. Encuentro Sonidero in Tepito and Baile Sonidero at the closing of the Transitio Festival, Mexico City, produced as part of the Tianguis Transnacional series (October 19-20, 2007). Begun in 2004, the Tianguis Transnacional series is an exploration of the aesthetic, social, and political manifestations of informal trade. It pays particular attention to the informal economy’s social networks and material culture as they exist in the current context of globalization, and its related history of colonialism. The word “transnacional” may be seen as a simple yet significant Spanish intervention in the globally recognizable “transnational.” The word “tianguis” is more obscure. It is a Nahuatl (Mexican Indigenous language) word that has survived five hundred years of colonization, and in the process has undergone very meaningful transformations. Used in pre-Hispanic times by the inhabitants of the Aztec empire, this word simply meant “market” or the equivalent of our contemporary “shopping mall.” In contemporary Mexican Spanish, however, tianguis has become a prominent synonym of informal trade, illicit street stands, and the so-called black (or gray) market. The hegemonic Aztec “mall” has been thrown onto the street by the Spanish colony. The Indigenous street keeps fighting back, though, refusing to forget the meaning of the word, and insisting on the daily practice of a tianguis that threatens the very foundations of social and economic control, colonial urbanism, and its state taxation system.

The deepest manifestations of decolonial art and culture are not those of philosophers, politicians, and artists, but those produced collectively by shifting populations (migration) and social movements (culture).

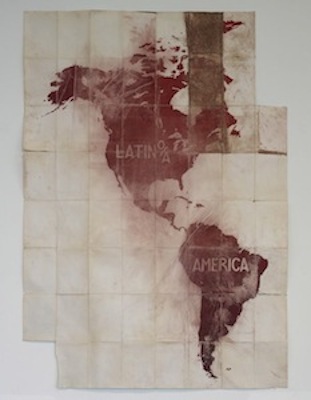

Image 2. Route Guides, maps transported by migrants, LATINO/A AMERICA series (2003-present). The linguistic and cultural impact that colonized populations have had on their colonizers is one of the clearest examples of this proposition. The phenomenon strengthens as colonial processes increase mass migrations of colonial subjects towards colonial centers of power. The LATINO/A AMERICA map series registers, for example, a new “Latinidad” that extends globally, redefining the English-speaking world. We are changing what “America” means, and what it means to be “American.”

Image 2. Route Guides, maps transported by migrants, LATINO/A AMERICA series (2003-present). The linguistic and cultural impact that colonized populations have had on their colonizers is one of the clearest examples of this proposition. The phenomenon strengthens as colonial processes increase mass migrations of colonial subjects towards colonial centers of power. The LATINO/A AMERICA map series registers, for example, a new “Latinidad” that extends globally, redefining the English-speaking world. We are changing what “America” means, and what it means to be “American.”

The globalization of our times begins with the exploitation of the American continent and the genocide of its original populations. Contemporary neoliberalism is only the most recent phase of a continuous colonial process.

Image 3. Global Indianization (2009-present). This map merges English, Spanish, and French to produce a new cartography based on the meanings of the words “Indian” and “indigenous.” Providing the foundation for our current processes of globalization, the map returns to the image of ignorance and confusion experienced by Europeans upon their arrival at the American continent. As a future or contemporary world order implied by the renaming of the continents, however, the map also registers the epic growth of cultural and political power accomplished by the very populations who have been accurately and mistakenly defined by the idea of the “Indian” and the “indigenous.”

Modernity is inseparable from coloniality. Decolonial aesthetics is therefore not modern, postmodern, or altermodern. It is rather the multitemporal movement of those who look and have looked to rebuild the world from the ruins of the modern/colonial system, with all the specifics of what this may look like in a given time and space.

Image 4. Coatlicue and Las Meninas (2008), no. 13 from the Black Mirror / Espejo Negro series (2007-present). This series began when the Nasher Museum of Art commissioned a new work from me to accompany their exhibition From El Greco to Velázquez: Art during the Reign of Phillip III. The Black Mirror / Espejo Negro book includes thirty-nine photographs of the installation I produced, as well as critical writings by scholars of various disciplines. The series as a whole, with its play of transparencies and reflections, makes impossible any separation between past-present, artwork-viewer-environment, or the pre- and post-Columbian. Coatlicue and Las Meninas, however, is the most iconic demonstration of the modernity/coloniality union. The work proposes two temporary installations. The first would bring the Aztec sculpture Coatlicue to the Museo del Prado in Madrid to display it in front of Las Meninas by Velázquez. The second would transport Las Meninas to Mexico City to be displayed in front of the Coatlicue at its habitual home, the National Museum of Anthropology. Both installations would include a large sheet of dark glass hovering between the works, integrating again — through transparencies and reflections — the artworks, their viewers, and their contexts. Not to be confused with the modern notion of mestizaje, these reflections allow the perception of simultaneous difference, copresence, and cotemporality.

A cultural practice that fights against the aesthetic and philosophical architecture of the modern/colonial organization of knowledge will hardly produce anything that fits neatly within its categories. Stylistic eclecticism, technological and technical hybridity, diversity of media, and an open disrespect for any linear notion of art historical progress, are common features of decolonial producers. Instead of being recognized as a sign of consistency, however, this “categorical nonconformity” of decolonial aesthetics is mostly represented as a lack of integrity, continuity, or purity by US/European modern and postmodern stances.

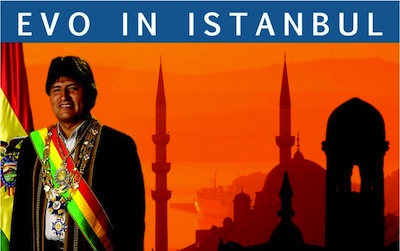

Image 5. Evo in Istanbul (2009). At its most basic level Evo in Istanbul proposed a coproduction of the artist, the curators (WHW), the staff of the 11th International Istanbul Biennial, and other interested individuals to create an official visit to the Istanbul Biennial by Evo Morales, President of Bolivia. The visit would include the standard ceremonial events associated with such a presidential visit: a guided tour of the Biennial, speeches, meetings with local and international politicians, media engagements, interviews, and so on. This superficial appearance of normalcy, however, would be layered with subtle and less subtle experiments in contemporary political theater, interventionist actions, and other gestures agreed on and developed by the collaborators, including President Morales. The very topics and questions set forth by the curators, their Brechtian framework, the accompanying ideological and aesthetic cracks exposed in the Biennial as an institution, as well as the political context provided by the city of Istanbul as it reverberated with its Bolivian guest, would become the very medium and content of this unique presidential visit. As a direct decolonial engagement with current political debates across an international left in its mainstream and underground ranges, the work would also critically confront recent contemporary art discourses seeking to depoliticize socially engaged cultural practice.

Decolonial aesthetics employs the tensions between different contemporary and anachronistic colonial powers as a source of creativity and resistance.

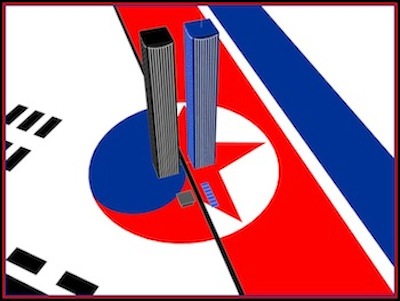

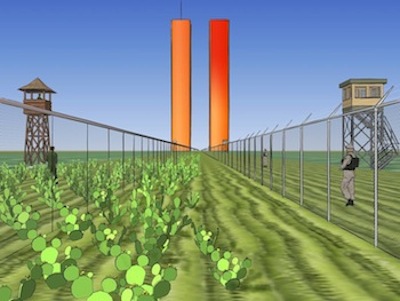

Image 6A (top). McSickle, logo created for 16 Beaver Group’s first International Lunchtime Summit (2003) produced at the Center for Contemporary Art in Vilnius, Lithuania, ACC Stiftung in Weimar, Germany, and twenty other cities around the world, among them Tucumán, Skopje, Krasnoyarsk, Los Angeles, Paris, and London. Images 6B, 6C, 6D (bottom). Simulations of Twin Tower reconstructions in Panmunjum between North and South Korea (top), Guantanamo Bay (middle), and Athens, Greece (bottom). Part of Twin Towers Go Global (2001-2011), included in Documenta 13 AND AND AND.

Conflicts among colonial powers are not a “clash of civilizations” as Samuel Huntington would have it, but a manifestation of the cracks in the global colonial system. Such tensions give life to these artworks: hammer and sickle join the “M” of McDonalds to reflect on the rise of China; and the Twin Towers appear in sites that would have lost their significance if the Cold War had really ended — Guantanamo Bay and Panmunjum, the so-called demilitarized zone between North and South Korea, which is actually the most militarized border on the planet. Unlike the much-celebrated destruction of the Berlin wall, the barriers erected here by both capitalist and Soviet imperialism are as strong as ever, maintaining a global colonial order.

It does not suffice to decolonize the aesthetics of the present; the past must also be infected. If Western art wants to remain part of any kind of universal canon — never again its equivalent — it must transform itself as radically in the past as in the present.

Images 7 and 8. WTC Kabul and WTC Baghdad, examples of twelve oil paintings that constitute the Phantom Limbs museum installation (2001-2011). Between 2001 and 2011, I produced works in new and old media in which the Twin Towers appeared to be reconstructed identically and to scale in various places around the world. WTC Baghdad (above) shows the towers exactly where the largest US Embassy in the world is located, right in that city’s Green Zone. The conscious use of pictorial styles, techniques, and compositional devices associated with the Western canon is here employed as a decolonial method. Simulation, mimicry, and overidentification create a critical mirror image of modern/colonial power. The book Grand Gestures & (Im)modest Proposals, produced for the Documenta 13 AND AND AND series, focuses on these works and ideas.

Powerful decolonial enunciations often come from historically excluded colonized spaces, but critical voices that speak from the center of colonial power are also crucial. The repercussions against speaking from either position can be harsh. We live and work in the belly of a global beast.

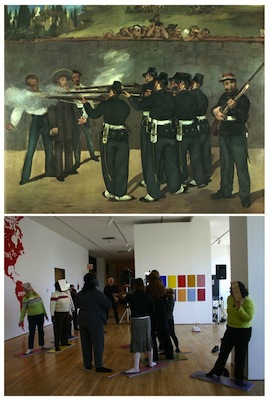

Image 9. The Execution of Maximiliano (Part 2), Naturalizations series. This work encourages the public to reenact Manet’s The Execution of Maximilian by wearing the mirror masks provided and standing on the platforms on the floor. Ten visitors are needed to create a tableau vivant based on Manet’s famous depiction of the event, but the re-enactment can also be done with fewer people. Participants shoot photographs instead of bullets. Produced and first exhibited in New York at the time of the iconic Internet beheadings of the insurgency in Fallujah and Iraq (2006), the work presents a historical arc of artists and intellectuals whose art speaks against the violence of the very states they inhabit. Manet’s painting was banned for many years because it was understood to speak against French imperialism, from within France. Sartre’s justification of the Paris bombings against the Algerian occupation was also silenced. Few people in the US and Europe — even amongst those opposed to the Occupation of Iraq — have spoken publically in favor of the Iraqi insurgency. The few who have are quickly silenced through exclusion, or stigmatized through claims that directly associate them with “terrorism,” that convenient and always adaptable word of the colonial linguistic arsenal.

Financial colonialism and the transnational military-industrial complex are the areas of highest cooperation and coordination of modern/colonial states and their elites. To confront them, decolonial aesthetics will use actions and social forms that may never be recognized as art.

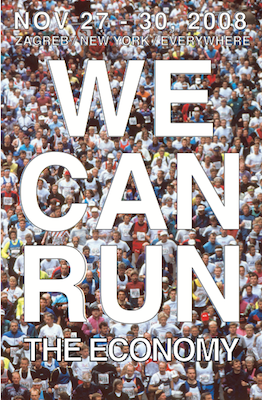

Image 10. Poster created for “We Can Run . . . the Economy” (2008), a project by 16 Beaver and Brian Holmes at the Galeria Nova in Zagreb, Croatia, for the WHW collective in preparation for their work as curators of the 2009 Istanbul Biennial. The endocolonialism applied by national governments to their own citizens is becoming ever more clear and visible. The antidemocratic use of taxes, bailouts, massive transfers of wealth, antilabor policies, and systematic debt imposed on individuals and institutions by transnational banking are all measures that colonized nations and subjects are extremely familiar with through centuries of exposure. Because many former beneficiaries of colonial economics are now being colonized by their own elites in Europe, precarity has become a hot topic of “global” concern. The populations of ancient and modern colonial powers, such as Greece, Italy, and Spain, are now subjected to the financial colonialism represented by Germany, France, and the European Union. In a series of echoes reminiscent of Goya’s famous painting of Saturn devouring his children, the centers devour the colonies, Europe devours its nations, and its nations devour its citizens. We would benefit from a higher awareness of the very relevant history of Haiti, the first American nation to free itself from the colonial yoke of slavery, but also the first to have it immediately replaced by an imposed colonial regime of insurmountable foreign debt.

To the decolonial artist, economists’ projections are nothing but powerful fictions, and these works of the imagination may be counteracted by our own decolonial speculations and projections. While often using humor as a cultural device against the force of colonial rationalism, the tragic conditions of the colonial subject rarely allow for the detached irony so prevalent in the elite circuits of specialized contemporary art.

Image 11. Take Me to the Top: The Fine Art of Finance (2012). Produced for the Wide Open School exhibition, Hayward Gallery, London. The above images show views from the London Eye capsule during the event. Photos of the project were taken by the instructors, workshop participants, and Cliff Lauson, curator of the work. What better location for an elite seminar on the culture of business than the London Eye and its private capsules? Two instructors were invited to collaborate with me in this work, and each of us was in charge of a specific segment of the seminar. Sverre Spoelstra, from Lund University’s Department of Business Administration, focused on the vast leadership literature he regularly writes and lectures on. Stefano Harney, Chair of Queen Mary’s School of Business and Management at the University of London, led a unique business meditation-session at the very top of this enormous ferry wheel’s rotation. The conclusion was a presentation of thirty-two transparencies I prepared and fixed to the capsule’s glass windows to argue for the necessary transformation of our business culture from one of ‘fear and greed’ to one of ‘self-sacrifice’ from our leaders. While we could not foresee that the LIBOR scandal would erupt during these days, or that the Shard pyramid building would be inaugurated on the very day of our action, we surely integrated these events into the artwork.

Decolonial aesthetics understands that social and ephimeral art are the most common and relevant cultural forms in global history. The US/European obsession with periodizing these practices as if they had been invented by a recent avant garde is simply another territorial demarcation in the colonial tradition of taking possession of that which has been cultivated by others.

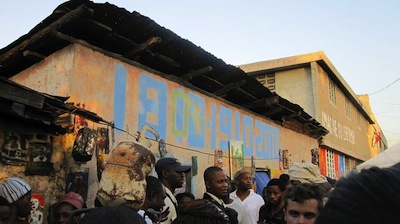

Images 12A, 12B, and 12C. Top: Missing Reflection, Naturalizations series. Work created with Esther Gabara and local collaborators in Port Au Prince, Haiti, for the first edition of the Ghetto Biennale (2009). Bottom: Independence, Revolution . . . Narcochingadazo (2009-present), work created with Miguel Rojas-Sotelo and collaborators around the world. These images from Port-au-Prince, Haiti, were taken two weeks before the disastrous earthquake of January 2010. The Naturalizations series is based on collective experimentation with mirror masks. These are often used to challenge the senses and rethink social structures, the perception and production of space, as well as notions associated directly with the human face, such as race, affect, and gesture. The above image shows high school students playing with the masks to engage with Frantz Fanon’s writings. In the Narcochingadazo series, the secular anniversaries and celebrations of postindependent states are used as a backdrop to explore a conceptualism based in poverty, the politics and aesthetics of numbers, as well as cultural strategies that may nourish the histories erased or obscured by official national celebrations. In the above mural from the Grand Rue neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, the date of the Haitian Revolution is reinscribed on the dates of the later Independence celebrations across the American continent that have often erased it.

Critical forms of folklore and popular expressions are important manifestations of decolonial aesthetics, but their awareness of past and current colonial structures makes them actively resist any ethnic, nationalist, or cultural essentialisms.

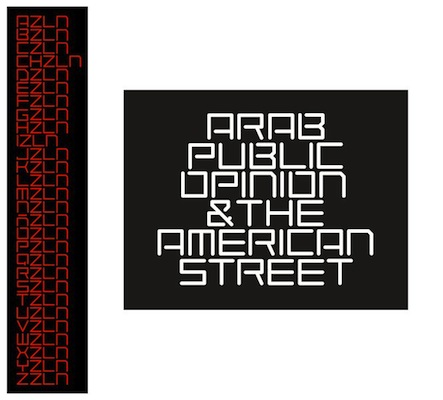

Images 13A and 13B. Left: ABCZLN: Retomando la palabra, reinventando el alfabeto (2004); right: Arab Public Opinion & the American Street (2006). In 2000 I began maintaining a practice of using font design and simple image/text constructs for specific political situations and social contexts. The same patterns are used to produce banners and t-shirts for protests, weavings to be worn at any occasion, and artworks to be hung on exteriors or interiors of buildings or painted directly on the wall. Expanding on the already existing EZLN and FZLN, the series of weavings and prints called ABCZLN imagines a myriad of additional possibilities for this continuously inspiring decolonial movement based in Chiapas. Arab Public Opinion & the American Street reverses the conventional racism and paternalism with which US/European media regularly address the social movements and political structures of Arab-speaking nations to this date. The design has been used in various decolonial contexts, but also in settings where people would rather use the concept of “de-Westernization.” An adapted version of this work called Arab Public Opinion & the English Street has been used in the UK and Commonwealth contexts.

Language is a fundamental vehicle of colonial imposition, but it is also the bridge to shared memories and the solidarity of resistance. Colonial subjects tend to be polyglots. Decolonial aesthetics is therefore often born in conversations among several languages.

Image 14. Official logo with Farsi announcement for the International Day Without English (December 18, 2011). The first edition of this work (2011) was created in response to an international call by the United Nations, Creative Time, the Queens Museum of Art, and Tania Bruguera’s Immigrant Movement International. On the one hand, International Day Without English proposes to reform monolingual English speakers through a kind of linguistic fasting period. It also encourages people who speak other languages to let them be seen and heard on that day. But this global day without English could also be adapted to a Day Without Spanish in places where that language is still used to repress dozens of contemporary indigenous languages, such as Nahuatl, Zapotec, Maya, Quechua, and Aymara. Likewise, a Day Without Russian could be celebrated in countries that were subjected by the former Soviet Union. We will see on this day, each year, how truly vehicular our assumed lingua franca really are.