In the nineteen-teens, Concepcion García, a Mexican national, lived in Texas to attend school. In April 1919 she became ill, and attempted to return home. That same month Lt. Gulley of the U.S. Cavalry patrolled the U.S.-Mexico border. While crossing the river back to Mexico on a raft, Concepcion, her mother Maria, and her aunt found themselves under fire. Her father Teodoro looked on from the Mexican bank as Lt. Gulley shot and killed his daughter.[1]Teodoro García and M.A. García (United Mexican States) v. United States of America (1926).

That same month a court-martial dismissed Lt. Gulley from military service for firing at an unarmed group. However, on the advice of the secretary of war, the US President reversed the findings. This action restored the lieutenant to active military service five months later.[2]Under the jurisprudence of the commission American citizens filed a nearly three thousand claims against Mexico and Mexican citizens filed almost 900 against the United States.

Unsatisfied with U.S. military procedures, Concepcion’s parents filed a claim through the U.S.-Mexico General Claims Commission of 1923. They charged the United States with a denial of justice, a violation of the international standards concerning soldiers taking human life, direct responsibility in the death of their daughter, and failure to punish.[3]J. G. de Beus. The Jurisprudence of the General Claims Commission United States and Mexico: Under the Convention of September 8, 1923. (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1938) 1-10. The Commissioner … Continue reading

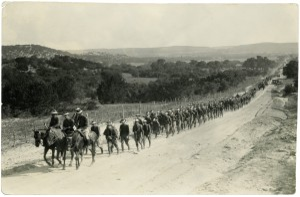

On December 3, 1926 the commission found that according to military bulletins, “firing on unarmed persons supposed to be engaged in smuggling or crossing the river at unauthorized places, is not authorized,” and that the shooting of the unarmed Concepcion García constituted a punishable crime. Moreover, the commission found it the duty of municipal authorities and of international tribunals “to obviate any reckless use of firearms.” Accordingly the commission obligated the US Government to pay $2,000, in behalf of Concepcion’s parents.[4]For image used: “Convoy of Foot Soldiers,” Steve and May Bennett Collection, Archives of the Big Bend, Bryan Wildenthal Memorial Library, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, Texas.

In other words, the United States accrued a $2,000 debt for the murder of Concepcion García by a U.S. soldier.

The commission’s attempts to penalize national governments held liable for murdering foreign citizens by charging them to pay an indemnity exposes judicial failures to accurately assess human loss and to change military and law enforcement practices. Examining the claims commission shows, first, that families that survived violent crimes actively sought justice for their deceased family members, second, that international courts employment of national debt did not represent an act of justice served. Instead, an investigation into this claim shows that the General Claims Commission functioned to resolve international turmoil but failed to resolve the loss experienced by surviving family members. This short essay first gives a short background on the commission within the context of violent turmoil on the U.S.-Mexico border in the early twentieth century. Next, this piece outlines the shortcomings of the commissioner’s calculation of indemnities for claimants. Finally, the writing concludes by situating the García case within a long and continued history of violence on the Rio Grande River.

U.S.-Mexico General Claims Commission of 1923

The start of the Mexican Revolution initiated widespread political instability in Mexico that lead to a calamitous rise in claims filed through the U.S.-Mexico General Claims Convention of 1923.”

[5]For more on movement in the U.S.-Mexico border region during this period see: Montejano, Young, Stern.

This committee aimed to amicably settle claims filed by citizens of each country against the other.[6]Teodoro García and M.A. García (United Mexican States) v. United States of America (1926) 130, quoting Annual Report pp 16-17, (1924) of the General Commissioner General of Immigration of the … Continue reading

While the majority of the cases dealt with loss of property, thirty-two claims charged nations with denial of justice, wrongful death, unnecessary use of arms, or direct responsibility in the death of their relative.

With the rise of nationalism at the end of the nineteenth century, both the Mexican and the U.S. government took interest in patrolling their borders.[7]J.W. and N.L. Swinney (United States of America) v. United Mexican States (1926).

The surge to militarize the border disrupted a regional population that lived fluidly in the borderlands. Bound by tight economic, political, and cultural connections this population frequently traversed the geographical boundaries.”[8]Teodoro García and M.A. García (United Mexican States) v. United States of America (1926) 130, quoting Annual Report pp 16-17, (1924) of the General Commissioner General of Immigration of the … Continue reading

The Rio Grande River itself became a site of state violence and five cases heard by the commission dealt specifically with shootings by either U.S. or Mexican officials firing on individuals while crossing the national border. In a report by the US General of Immigration he described the difficulty for military personnel to prevent people from moving back and forth across the river. He quotes, “The river is not wide at certain seasons of the year …it becomes a mere trickle.”[9]Teodoro García and M.A. García (United Mexican States) v. United States of America (1926) 130, quoting Annual Report pp 16-17, (1924) of the General Commissioner General of Immigration of the … Continue reading

Particularly in south Texas, patrolling the international border became an arduous task for soldiers. During the hearings the tribunal noted the frequency in which soldiers prioritized policing the border over valuing individual life. In particular, the commission aimed to correct soldiers and municipal agents indulging in the act of firing before sufficiently proving delinquency. The commissioners wrote, “Human life in these parts, on both sides [of the river], seems not to be appraised so highly as international standards prescribe.”[10]Chakravarti, pg 233. “More Than Cheap Sentimentality”

Violent racial conflicts ensued and it’s estimated that in the decade between 1910-1920 approximately 5,000 ethnic Mexicans died at the hands of soldiers, Texas Rangers and Anglo vigilantes in the U.S.-Mexico border region.

Unquantifiable Life

In the case of Mexican national Concepcion García the commission found that Lt. Gulley’s actions constituted a punishable crime and obligated the U.S. Government to pay an indemnity to resolve the debt owed to her parents.[11]“Report of International Arbitral Awards: General Claims Commission (Convention of September 8, 1923) United Mexican States, United States of America) 4 Feb 1926 – 23 July 1927 Vol 1V pp … Continue reading

In deciding the amount, the committee not only considered “reparation of pecuniary loss,” but also, “satisfaction for indignity suffered…An amount of $2,000 without interest, would seem to express best the personal damage caused the claimants by their killing of their daughter by an American officer.”[12]L.H. Woolsey. “The United States-Mexican Settlement,” The American Journal of International Law. Vol. 36, No. 1 (Jan., 1942) p 117-118.

How the commissioners determined reparation of pecuniary loss and indignity suffered begs further investigation. Commissioners estimated the financial loss owed a claimant by calculating the victim’s probable life expectancy and the potential money made throughout their working life. Thus, indemnities instead reflected only the class status of victims and therefore proved unable to quantify human life beyond their value as wage laborers. In determining the indemnity commissioners did not outline how they calculated personal damage or indignity suffered. This oversight exposes the tenuous ability of the commission to adequately assess and reconcile grieving survivors. But how could one calculate grief?

In addition to the commissions’ limited abilities to quantify life and grief, the tribunal’s influence remained restricted to allotting financial indemnities but could not advocate the prosecution of any assailants. With the commission bound to the realm of fining national governments, the systemic sanctioning of reckless use of firearms by soldiers and local law enforcement officers went unimpeded. As such, the indemnity did not call for the prosecution of Lt. Gulley, penalize the military courts for denying the claimants justice, or challenge the sovereign power of the president of the United States to sanction military tactics on the border that threatened human life. To the contrary, the president’s reversal of the court-martial that dismissed Lt. Gulley from military service created a precedent that excused soldiers for recklessly using firearms in the act of enforcing prohibitive laws. In this light, enforcing domestic laws at the international border continued to be the United States’s priority in the early twentieth century to the detriment of border communities.

While the García case shows that governments could be held liable for the actions of their soldiers, the case also shows how illusive “justice” can be. Scholars have recently turned to study the long-term legacy of state sanctioned practices of genocide, ethnic cleansing, and war crimes and grapple with social remedies for lasting social traumas. The role of international commissions, such as the general claims commissions in the early twentieth century and the more recent form of truth commissions, in judging what constitutes a punishable crime leave much to be desired in the way of making social change.

In her study of truth and reconciliation commissions in the twentieth century political theorist Sonali Chakravari argues that when commissions make room for personal testimonies these accounts have the ability to “educate, empower, and hold others accountable.” But, she continues, truth commissions and institutions of transitional justice must redefine what we think of as justice for war crimes and state sanctioned terror. In her own words “justice” must go beyond, “accountability and punishment in order to include the emotions of victims and the legacy of suffering that affects entire societies after war, not just perpetrators and victims.”[13]Concepcion Carrasco de Gonzalez, et. al. (United Mexican States) v. United States of America (1926).

For the parents of Concepcion García, the money seems insufficient to account for their financial loss, and the emotional trauma suffered from witnessing the murder and the later justification of Concepcion’s death by the U.S. military. But, at the very least, they had their day in court. In November 1941, the two governments decided on an en bloc settlement where Mexico agreed to pay approximately $40 million, while the United States agreed to pay just over $500,000.[14]Dan Glaister. “Death at US-Mexico Border Reflects Immigration Tensions.” The Guardian March 4, 2008. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/mar/04/usa.mexico

The national debts owed by each country were accrued through decisions of individual claims. In considering Mexico’s large debt acquired through the claims settlements, the United States agreed to negotiate a reciprocal trade that aimed to stabilize the Mexican peso by purchasing pesos with U.S. dollars. In addition, the U.S. government agreed to purchase Mexican silver from the Mexican government and to extend the credits through the Export-Import Bank to Mexico for the construction of the Inter-American Highway. In these terms, resolving individual indemnities took the form of international debt negotiations. This resolution helped the U.S. gain access to Mexican natural resources under favorable conditions and literally paved the way for future trade through the construction of a highway that would link the two nations.

While the en bloc settlement signaled the “amicable” settlement of national tensions created by these claims, in rushing to end the international tensions and resolve financial debts, the commission failed to hear all outstanding claims. In total, the commission did not consider over one thousand claims before protocol expired.

One of the outstanding claims included Concepcion Gonzalez et. al. v. United States of America. Twelve claimants in this case charged the United States with direct responsibility of the deaths of their family members in what is known as the Porvenir Massacre of 1918. This tragedy took place in west Texas when the U.S. Cavalry aided Company B of the Texas Rangers in executing fifteen ethnically Mexican men ranging in age from 16-64 years old.

Thus, the en bloc settlement officially closed the door for families like the survivors of the Porvenir Massacre still waiting to have their cases heard. Rather than signal a resolution for the families of all victims, the commission merely succeeded in calming diplomatic tensions arising from outstanding claims. This resolution further increased Mexico’s financial debt to the United States and heightened the national disparities in power relations between the two nations.

Conclusion

The García case shows that although governments accrued national debts, these fines did not resolve or correct state-sanctioned violence. The commission did not fully considering the emotional trauma experienced by families nor did it prosecute crimes. Paradoxically, national debts specified by the commission helped alleviate national governments of responsibility to individual claimants by tallying all indemnities into a total sum to be negotiated. Fining a nation for the murder of innocent victims did not resolve state-sanctioned violence. Instead, this research reveals national governments as both the convicted and the beneficiaries of state sponsored violence.

The U.S.-Mexico Claims Commission of 1923 functioned to settle international claims that caused diplomatic tensions for the two North American nations. However, individual cases in which the commission found national governments liable for loss of life can inductively illuminate debates about the long-lasting effects of the construction and militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border. This research helps to recover these cases from international archives and to introduce a long history of survivors who resisted military and municipal officials’ reckless use of firearms in this region. Although decisions by the commission have garnered little attention from legal historians, I agree with Chakravarti, who claims that judicial proceedings and victim testimonies have the potential for reconciliation and social transformation through public education. In this case, further study of this historical period and the commission’s findings has the ability to illuminate present day immigration debates about the current state in which loss of life on the U.S. Mexico border is a regular occurrence.

In December 2006 Francisco Javier Dominguez-Rivera, a twenty-two year old Mexican national traveled back from his factory job in New York City to visit his family in Morelos, Mexico for Christmas. In January 2007 he planned to return to New York with his two brothers, and one of their girlfriends. During their travel across the U.S.-Mexico border on January 12, just 100 yards north of the border, Border Patrol officer Nicholas Corbett approached the group and shot and killed Dominguez-Rivera. Corbett became the first agent tried for murder since 1994. In federal court in Tucson, AZ prosecution charged Corbett with second-degree murder, manslaughter, and negligent homicide, but twice the proceedings ended in mistrials leaving prosecution not to seek a third trial. U.S. courts in Tucson, AZ continue a long history of judicial proceedings that fail to prosecute state agents for negligent homicide. In an interview published in The Guardian in 2008, the son’s father Renato Domínguez explained that his family intended to seek an indemnity for the death of his son.[17] The earlier failures of the U.S.-Mexico General Claims Commission of 1923 raise questions of how judicial proceedings will grapple with the impossible task of quantifying human life and assessing personal damage. However, until national governments decide to privilege human life above prohibitive laws, the loss of life on the U.S-Mexico border will continue to rise and the lasting impact will prove to be unquantifiable.

References

| ↑1 | Teodoro García and M.A. García (United Mexican States) v. United States of America (1926). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Under the jurisprudence of the commission American citizens filed a nearly three thousand claims against Mexico and Mexican citizens filed almost 900 against the United States. |

| ↑3 | J. G. de Beus. The Jurisprudence of the General Claims Commission United States and Mexico: Under the Convention of September 8, 1923. (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1938) 1-10. The Commissioner representing the Mexican Government was Fernandez McGregor, for the United States Edwin Parker succeeded by Fred K. Nielsen, and the presiding commissioners were C. von Vollenhoven of the Netherlands succeeded by Kristen Sinballe of Denmark followed by H. F. Aljaro of Panama. The Commission was comprised of one person selected by the President of the United States, one person selected by the President of the United Mexican States, and one person, who presided over the commission, mutually decided upon by both nations. |

| ↑4 | For image used: “Convoy of Foot Soldiers,” Steve and May Bennett Collection, Archives of the Big Bend, Bryan Wildenthal Memorial Library, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, Texas. |

| ↑5 | For more on movement in the U.S.-Mexico border region during this period see: Montejano, Young, Stern. |

| ↑6, ↑8, ↑9 | Teodoro García and M.A. García (United Mexican States) v. United States of America (1926) 130, quoting Annual Report pp 16-17, (1924) of the General Commissioner General of Immigration of the United States. |

| ↑7 | J.W. and N.L. Swinney (United States of America) v. United Mexican States (1926). |

| ↑10 | Chakravarti, pg 233. “More Than Cheap Sentimentality” |

| ↑11 | “Report of International Arbitral Awards: General Claims Commission (Convention of September 8, 1923) United Mexican States, United States of America) 4 Feb 1926 – 23 July 1927 Vol 1V pp 1-769 (United Nations, 2006). Herbert W. Briggs. “The Settlement of Mexican Claims Act of 1942,” The American Journal of International Law, Vol. 37, No. 2 (Apr, 1943) 222. Some of the claims, filed more than 60 years prior, awaited awards made by the United States-Mexican General Claims Commission in favor of the claimants more than 15 years earlier. |

| ↑12 | L.H. Woolsey. “The United States-Mexican Settlement,” The American Journal of International Law. Vol. 36, No. 1 (Jan., 1942) p 117-118. |

| ↑13 | Concepcion Carrasco de Gonzalez, et. al. (United Mexican States) v. United States of America (1926). |

| ↑14 | Dan Glaister. “Death at US-Mexico Border Reflects Immigration Tensions.” The Guardian March 4, 2008. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/mar/04/usa.mexico |