In August, I attended a screening of Aurora’s Sunrise at the New Plaza Cinema. The documentary depicts the annihilation of Armenian lifeworlds in the Ottoman Empire at the beginning of the twentieth century. In August, the film was received as an archival project. Viewers did not yet know that it was also a premonition.

Only weeks later, the mass deportation of Armenians from Artsakh was documented on digital screens and set to the epistemic violence of denialism. Descendants watched ancestral narratives retold and relived in real time. Losses mounting in the present were superimposed over the losses of a century ago, a palimpsest of expulsion flickering into view as we looked on.

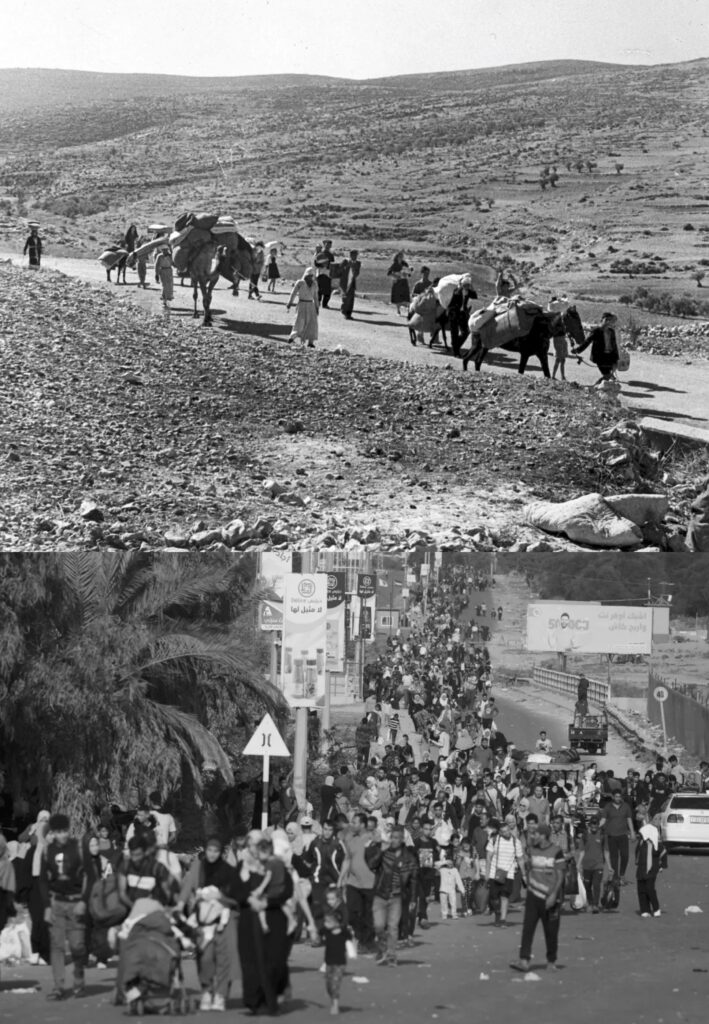

By September’s end, the exodus of more than 100,000 Artsakhtsis along the five-kilometer Lachin Corridor formed a serpentine pattern visible from space. Recorded by Maxar Technologies satellites, images of the scene would find their way into photographic diptychs that circulated across digital platforms. In the diptychs, the satellite captures are arranged alongside historical photography of Armenians on death marches through the Syrian desert to Deir ez-Zor.

The diptychs’ images are labeled “1915” and “2023,” respectively.

By early October, an ongoing campaign of genocidal violence had intensified in Palestine, killing thousands and laying claim to the lifeworlds of millions. Most among them were refugees several times over, who had already watched each generation before them dispossessed. As Palestinians experienced mass deportation from their homes in northern Gaza, journalist Amjad Shabat observed, “I saw cars lined up for a stretch of over 15 kilometers…It was a similar scene that my grandmother described many times about the Nakba.” Diptychs were composed juxtaposing the present march southward with photographs from seven decades ago.

They are labeled “1948” and “2023,” respectively.

Each diptych, each doubling of Armenian and Palestinian catastrophe, also contains within it the possibility of a triptych, a quadtych, a polyptych. Each of its panels is an index of the recursivity of colonial violence, a structure whose horror is infinitely iterable. Beyond the diptych’s frame is an n-dimensional plane of atrocities spanning multiple spatiotemporal coordinates, not pictured.

These diptychs attest to the transhistorical linkage of Armenian and Palestinian liberation struggles, surfacing their contiguities as well as their asymmetries and points of divergence. The discrete struggles they visualize are woven together by interlocking threads of resistance to forces of occupation; the normalization of genocidal violence; petro-capital; circuits of US military funding; and the framing of Indigenous populations as eradicable obstacles to the project of building settler states.

Those of us familiar with these scenes through their ancestral transmission clamored that we have seen them before. We know what appears next, who disappears, if they are met with inaction. The recursive loop of colonial violence produces subjects, witnesses, who can predict what the next image in a diptych will be with an accuracy usually–and mistakenly–imputed to algorithmic prediction.

Against this backdrop, one of my elders tells me, “Our ancestors’ photographs are repeating themselves.”

What does it mean to be from a place in the world where scenes of catastrophe reappear from one century to the next, but remain invisible in both temporalities?

*

In the weeks that followed that August screening of Aurora’s Sunrise, the historical events it depicts appeared again.

Since December 2022, the people of Artsakh had been held under an illegal blockade by the petro-rich, authoritarian, ethnostate of Azerbaijan. It acted with the fulsome support of Turkey, with whom it shares the motto, “one nation, two states.” Turkey maintains a juridically enshrined policy of denial regarding the Armenian Genocide it perpetrated in 1915, and criminalizes reference to the genocide as an offense punishable by imprisonment. Both states’ officials espouse the ethnoterritorial ideology of Pan-Turkism. The mayor of Azerbaijan’s capital city openly stated in 2005, “Our goal is the complete elimination of Armenians.” He was subsequently advanced to the post of Deputy Prime Minister.

Disregarding millennia-long historical records that attest to Armenian Indigeneity in the region, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev has announced, “Nagorno-Karabakh is our land.” As well: “This is the end…We are chasing them like dogs.” Azerbaijan’s officialdom routinely deploys similar dehumanizing language to describe Armenians and plainly signal genocidal intent. This tendency toward genocidal rhetoric is shared in common with Israeli officials, who have referred to Palestinians as “human animals” and “children of darkness” subject to the “law of the jungle.”

In August 2023, after eight months of blockade, a report issued by a founding prosecutor of the International Criminal Court classified the situation in Artsakh as “genocide by starvation.” Food, fuel, and medicine were withheld from the population. The delivery of humanitarian aid was prohibited. Then, on September 19th, Azerbaijan launched attack drones, artillery, and rocket systems targeting Artsakh’s civilians and civilian infrastructure under the guise of “anti-terror” operations. After a day of continuous shelling, the Republic surrendered and its President, Samvel Shahramanyan later signed a decree indicating that the state would “cease to exist.”

By September’s end, the 120,000 Indigenous Armenians of Artsakh had been forcibly expelled from the land their ancestors had lived on and with for millennia. Today, as few as fifty Armenians remain.

In October, Azerbaijan announced its intention to settle 140,000 Azerbaijanis on occupied Armenian lands by 2026. These settlers will one day amble across a street in occupied Stepanakert newly renamed for Enver Pasha, a primary engineer of the 1915 Armenian Genocide.

*

Our ancestors’ photographs are repeating themselves, even as they remain invisible to global observers.

One photograph in particular repeats itself to me with some regularity. It belongs to a genre of documents common to Armenian family archives: images of people who existed before 1915 and did not exist afterward. This yellowed portrait depicts my great-grandfather, a rug merchant, and his wife in Van—what was then Western Armenia and is now Turkey. They make a striking couple, distinguished in the finery they wore for the photograph. Each projects an air of effortless regality. His gaze is directed beyond the frame of the image and hers unflinchingly confronts the camera.

The two later fled Van during the genocide, which he survived and she did not. They were stopped on their escape route and momentarily separated when a gun was fired. He returned to find that she had died after sustaining a terror-induced heart attack when she heard the shot ring out.

The first time this story was told to me, I wondered how he could be certain that it was the terror that claimed her life? As a child born in Armenia but educated in the nucleus of US empire, I had learned to expect that even in death, she was obliged to provide substantiating evidence of the cause of her suffering.

Since September, this photograph repeats itself to me every day.

*

Under blockade and eventual bombardment in 2023, Armenians in Artsakh produced a vast archive of visual records documenting the genocidal conditions to which they were subjected, and exhorted the world to bear witness.

Ghostly images of empty supermarkets and their vacant shelves circulated for months.

A video depicted a twelve-year-old child spending the night queuing in a bread line to retrieve his family’s daily ration in the morning, often returning home without food because supplies were exhausted.

A convoy of blocked humanitarian aid trucks sat parked on the Lachin Corridor in plain sight.

A picture shared by Stepanakert-based journalist Siranush Sargysan showed children huddled in a bomb shelter accompanied by the caption, “Sleeping with kids who yesterday dreamed of bread & today dream of waking up tomorrow. I don’t know if we will wake up but I hope you will remember us for resisting this genocide with honor.”

Documentation of mutilated bodies, a bombed kindergarten building, and devastated civilian infrastructure proliferated.

What would it take, I wondered, to compel observers to look at these images? To see that our ancestors’ photographs are repeating themselves?

After completing the ethnic cleansing of Artsakh, Azerbaijan began to seed its intention of invading and annexing the sovereign territory of Armenia. A recent statement from its foreign ministry alleges that Armenians in eight villages internationally recognized as Armenian territory are impeding peace and security by “occupying” their own ancestral land.

Global commentators will issue warnings. Human rights agencies will point to evidence of explicitly genocidal intent. Visual documents of regime-made disaster will circulate across digital platforms. Writers will entreat you to look, as I am now doing.

*

One week after the forced displacement of Artsakh’s entire population was complete, the ongoing campaign to dispossess and displace Palestinians from Gaza intensified on an unfathomable scale.

At the time of writing, more than 24,000 Palestinians have been murdered, over 10,000 of them children. Over 825 multigenerational families have been erased from the civil registry, leaving no living trace of their ancestral lineages on the earth. At least 117 journalists, often alongside their families, have been targeted and killed. More than seventy percent of the housing in Gaza has been destroyed or damaged, and more than 1.9 million Palestinians have been displaced, totaling eighty-five percent of Gaza’s population. More than ninety percent of the population faces extreme hunger and starvation, with famine projected by February. The Ministry of Health has long since declared “the complete collapse of the health system and hospitals in the Gaza Strip,” as the continual bombardment of medical facilities continues. And still, it would seem that the world intends to look on until no Palestinians remain on their ancestral land.

The inaction that confronts documents of genocidal violence in Palestine attests to the limits of viewing regime-made disasters as a galvanizing political force. Those limits are brought into especially sharp relief in an asymmetrical scenario described by Ariella Azoulay as one wherein viewers “are able to observe the disaster from comparative safety, whereas those whom they observe…can have disaster inflicted upon them and who can then be viewed subsisting in their state of disaster.”

Or, as scholar Saree Makdisi puts it, “people seem not to see or to recognize Palestinian suffering because they literally do not see or recognize it.”

*

Confronted by the scenes in Gaza, Amjad Shabat writes, “I grew up hearing my grandmothers’ stories about the Nakba. Today I am telling the story of the 2023 Catastrophe.” I read her words alongside those of refugees newly displaced from Artsakh, who report having lived through the second Mets Yeghern—a term Armenians use for the 1915 Genocide, which translates to the “Great Crime.” What does it mean to witness these repetitions alongside one another: the Catastrophe and the Great Crime?

Crucially, the states that seek to erase Artsakh and Palestine have arranged themselves as a triptych, in a relation of triangulated power, petro-capital, and militarism in which the US comprises the third vertex. Not incidentally, some 40 percent of Israel’s oil is reportedly supplied by Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan’s state oil company (SOCAR) was among the six firms to whom Israel awarded licenses for natural gas exploration in the Mediterranean on October 29. On October 19, amidst the bombardment of Gaza, Azerbaijan sent Israel over one million barrels of oil in a 900-foot tanker called Seaviolet. The former’s petro-rich status has long insulated it against accountability for state violence, as detailed in a major investigation by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, revealing a multibillion-dollar laundering scheme connected to the Azerbaijani state.

On November 8, the Israeli Embassy publicly congratulated Azerbaijan on the occasion of its “Victory Day.” The victory in question refers to Azerbaijan’s ethnic cleansing of Armenians and seizure of Artsakh. Israel supplied Azerbaijan with an estimated 70 percent of the weaponry that created the conditions of possibility for this victory. It drew from an arsenal which historically comprises 80 percent US weapons imports, bolstered by 3.8 billion dollars of annual US military aid. At the same time that it was supplying Israel with three-fourths of its arsenal, the US sent roughly $808 million in aid to Azerbaijan between 2002 and 2020—all while failing to provide “detailed instructions about the information required for its reporting to Congress.” Only after the US-abetted ethnic cleansing of Artsakh was complete, the Senate voted on November 16 to block further military aid to Azerbaijan. Meanwhile, even as genocide proceedings are underway at the International Court of Justice, the Senate has voted against a resolution calling for scrutiny of military aid to Israel.

A recent statement from the nonpartisan Lemkin Institute for Genocide Prevention underscores the role of the US in facilitating genocidal violence across both Artsakh and Palestine. Entitled “Statement of Mourning for the Gazans and the World,” the text observes the following of the US and Israel:

It is worth noting that these two major military powers are committing genocide in Gaza only weeks after actively enabling genocide against another besieged people: the Armenians of Artsakh, who were forcibly displaced from their indigenous homelands by the Azerbaijani military in September. If the world allows these two powers to continue to act with this level of impunity, genocide will become the normative policy of both dictatorships and the world’s so-called democracies alike.

Reaching farther into the past, the histories of Armenians and Palestinians have long been intertwined. Armenian communities in Palestine date as far back as the fourth century, constituting the oldest Armenian diaspora in the world, with thousands more arriving as refugees amid the genocide in 1915 (25-7). During the Nakba, thousands of Armenians were also expelled from their homes and, per historian Bedross der Matossian, Armenian communities in “areas that became Israel were reduced to insignificance” (40).

In 2000, when Israel attempted to assume control of occupied Jerusalem’s Armenian Quarter, Yasser Arafat rejoindered, “The Armenian Quarter belongs to us and we and the Armenians are one people.” Armenians living in occupied East Jerusalem are granted the same status accorded to Palestinians: “residents but not citizens, effectively stateless.” As one resident of the Quarter told writer Nancy Kricorian of Armenians and Palestinians: “we breathe the same tear gas.”

As the continual bombardment of Gaza intensified, Armenians in the Quarter’s Goverou Bardez (Cows’ Garden) witnessed the storming of the grounds by armed Israeli settlers accompanied by attack dogs. The settlers claimed ownership of the property and threatened the Armenians present that they would “get them one by one.” One of these settlers has been linked to Israel’s Minister of National Security. An urgent communique was issued by religious leaders on November 16, warning that “the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem is under possibly the greatest existential threat of its 16-century history.”

Bulldozers have appeared at the location to tear down barricades constructed by its residents, aiming to appropriate the site of the world’s oldest Armenian diaspora for conversion into an ultra-luxury resort. Confronting settler violence and tear gas grenades, the Quarter’s Armenians have organized to wage collective struggle, writing that “the Cows’ Garden is not just a piece of land, it is a repository of memories.”

*

Immediately after seeing images of Armenians in the Cows’ Garden trying to hold dispossession and displacement at bay, I encounter a photograph by Belal Khaled. It documents the experience of a 90-year-old woman called Anaam who has been twice displaced: once from her village during the massacres of the Nakba, and now from northern Gaza. She makes the forced journey southward on foot across five kilometers, braced by individuals on either side who ballast her along the way. Khaled’s caption notes that after the first displacement, she “kept her return key in the hope of returning to her home.”

A contemporaneous photograph by Scout Tufankjian depicts a school in Aralez, Armenia that’s now welcoming refugees from Artsakh. In the school, there hangs a tapestry of keys representing those belonging to Armenians forced to flee their homes in 1915.

No symmetries or equivalences can be drawn between these images. But witnessing them alongside one another allows us to visualize the interconnected histories of ethno-territoriality and genocidal violence that create the conditions of possibility for each.

Armenians and Palestinians share in common the experience of lives made unlivable on ancestral lands. Most crucially, we share in common a resistance to forgetting, as we have repeatedly borne witness to projects that seek to decimate and subsequently forget the worlds we have made.

Kegham Djeghalian, a Jerusalem-born Armenian photographer, relocated his home and studio to Gaza where he documented the Nakba, the Six-Day War, and conditions of life in refugee camps. His images depict lifeworlds under threat of erasure: picnicking families, seaside gatherings, a record of a women’s art class that appears to be from the 1950s, its emulsion crinkling.

The Palestinian poet Najwan Darwish further attests to the persistence of collective memory. His poem, “Who Remembers the Armenians?” reads:

I remember them

and I ride the nightmare bus with themeach night and my coffee,

this morning I’m drinking it with themYou, murderer—

Who remembers you?

Diptychs documenting the repetitions of 1915 and 2023, 1948 and 2023, are instructive. Placed alongside one another, they become a grid of interlocking attempted erasures undone by refusals to be erased.

What does it mean to be from a place in the world where scenes of catastrophe reappear from one century to the next, but remain invisible in both temporalities? These scenes demand the cultivation of dauntless solidarities, a praxis of collective witnessing and coalitional action.

A particular form of intuitive knowledge accrues for descendants witnessing the recursion of colonial violence. A way of knowing whose transmission is embodied, transferred across generations. A kind of predictive faculty that enables an observer to see the next image in a diptych before it has appeared. This form of knowledge also presents a duty—a responsibility to speak, to act, to attempt to prevent future recursions from materializing.

Cover image: Clockwise from left: 1. Armenian children evacuated from Kharput by Near East Relief, 1922-23. Via the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute. (Source) 2. Palestinian refugees en route from Jerusalem to Lebanon on November 9, 1948. Via AP Photo/Jim Pringle, File. (Source) 3. Palestinians use Salah al-Din Road to flee towards southern Gaza Strip in 2023. Via Hatem Moussa/AP Photo. (Source) 4. Satellite image of Armenians deported from Artsakh on the Lachin Corridor on September 26, 2023. Via AP / Maxar Technologies. (Source)

This text is indebted to Jasbir Puar’s editorial insights.