Palestine is today’s Vietnam. Five decades ago, it was Vietnam’s anti-colonial struggle for independence—first against the French colonists and then against the US imperialists—that sparked international protest and solidarity. “Vietnam” became a synecdoche of the global Third World Liberation movement. Anticolonial and decolonial struggles around the world, from Algeria to Cuba to Rhodesia, looked to Vietnam as a source of inspiration: a small but mighty force of guerrilla fighters that eventually emerged victorious over the much more powerful United States. Meanwhile, in the heart of empire, American students, leftists, and antiwar pacifists rallied against the US War in Vietnam, leading to violent clashes across college campuses and city centers as university administrations and riot police tried to suppress their demands for justice.

Today, we see a similar tidal wave of international support and righteous anger on behalf of the Palestinian struggle for liberation, in response to the latest intensive wave of Israeli military and settler violence in Gaza and the West Bank. Of course, the asymmetrical “Israel-Hamas War” of October 7, as it is referred to by prominent media outlets, is but the continuation of a much longer project of Zionist settlement and Palestinian displacement, that commenced during the British Mandate of Palestine following World War I and the fall of the Ottoman Empire; was consolidated during the establishment of the State of Israel as a haven for displaced Jews in 1948, in the wake of the Holocaust; and intensified after the Six Day War of 1967, when Israel initiated its occupation of Gaza and the West Bank (and the Golan Heights, which it later rescinded). But the current political moment of Israeli suppression and Palestinian resistance marks a distinct historical shift.

Never before have we seen such global consciousness and public solidarity with the Palestinian cause. Long seen as a taboo topic in the West, “Palestine” has now become a flash point in a much wider critique of the ongoing forces of empire, militarism, and settler colonialism that continue to shape our contemporary world. Led by Palestinian activists in Palestine and across the diaspora, protests have again erupted across college campuses and city centers, from the so-called “Middle East” to the rest of Asia to Europe. Of course, today’s social context is different—Cold War anti-communism replaced by post-9/11 Islamophobia—but the patterns of outspoken activism and widespread repression eerily echo the fervor inspired by “Vietnam” during the 1960-70s. Today, in the United States, American protesters point out that when the White House sends billions of dollars of aid to Israel, it renders the US complicit in the tens of thousands of Palestinian deaths that we have witnessed in the past weeks, to say nothing of the past decades. Moreover, the longstanding solidarity of anti-Zionist Jews has become more visible, as emblematized by the demand for a ceasefire now that was organized by Jewish Voice for Peace in Washington DC and US Congress on October 18, as well as the strong presence of Jewish activists at the pro-Palestine demonstration at Grand Central Station in New York on November 10. In Israel, too, thousands of Israeli protesters have taken to the streets to critique Prime Minister Netanyahu’s handling of war; while most have called for greater prioritization of the hostages, others have extended their criticism to demand a ceasefire.

As I have written elsewhere, this is not the first time that Vietnam and Palestine have been intertwined in the global imagination. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Palestinian freedom fighters expressed solidarity with Vietnamese revolutionaries and included declarations condemning US imperialism in Vietnam in their public speeches and political platforms. They also, like other decolonization movements around the world, drew inspiration from Vietnam. Following General Võ Nguyên Giáp’s unexpected victory over the French in the 1954 Battle of Điện Biên Phủ, Palestinian soldiers took on the nickname “Giap.” In 1966, Khalil Ibrahim al-Wazir, also known as Abu Jihad, visited Vietnam to learn more about the Vietnamese struggle, and over the following years the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) sent several groups of Palestinian soldiers to train in Vietnam and learn their guerrilla tactics. Palestinian soldiers invited the Vietnamese, in turn, to visit the Palestinian military bases in southern Lebanon. In December 1969, Yasser Arafat, the iconic leader of the PLO for many decades, argued that Palestinians were fighting not only for themselves but for “the freedom of peoples who are fighting for their liberty and existence, the freedom of the people of Vietnam who are suffering like the people of Palestine, the freedom of all humanity from oppression, discrimination and exploitation.” In March 1970, he accompanied a delegation of Palestinian liberation fighters to Hà Nội to pay his regards to General Võ Nguyên Giáp. In a press interview later that year, Arafat again affirmed the “firm relationship between the Palestinian revolution and the Vietnam revolution through the experience provided to us by the heroic people of Vietnam and their mighty revolution.”

Vietnamese freedom fighters, in turn, expressed support for the Palestinian struggle for liberation. North Vietnam and the PLO established ties in 1968. In a message to the International Conference for the Support of Arab Peoples held in Cairo on 24 January 1969, Hồ Chí Minh, who could not attend in person, asserted that the “Vietnamese people vehemently condemn the Israeli aggressors” and “fully support the Palestinian people’s liberation movement and the struggle of the Arab people for the liberation of territories occupied by Israeli forces.” And when Arafat visited General Võ Nguyên Giáp in March 1970, he told Arafat: “The Vietnamese and Palestinian people have much in common, just like two people suffering the same illness”—that is, the illness of Western empire and its suppression of their liberation struggles.

The broader Third World Liberation movement also acknowledged the special relationship between Vietnam and Palestine. At the 1973 Tenth World Festival of Youth and Students in East Berlin, the PLO was invited to take up the “banner of the global struggle” from the Vietnamese freedom fighters, whose struggle was thought to have concluded after the signing of the 1973 Paris Peace Accords ending US combat in Vietnam. With North Vietnam’s victory against US imperialism seemingly secured, the Third World Liberation movement turned its attention to the next major anti-imperialist struggle: Palestine.

And yet today, while Vietnam has achieved independence, Palestine remains occupied. Roughly 4.5 million Palestinians live in the Occupied Territories (OPT) of Gaza and the West Bank; an even greater number of Palestinians reside in limbo in refugee camps, since their displacement following Israel’s foundation in 1948. Palestinians living in the diaspora are refused the right to visit their ancestral homelands, unless they have secured a Western passport—and even then, they suffer harassment and intimidation at Israeli airports and border crossings.

The Socialist Republic of Vietnam, meanwhile, in many ways has forgotten the promises of its own revolution. The single-party communist government has been accused of human rights abuses and suppression of free speech. Following its strong support of Palestine during the 1960-70s, Vietnam established diplomatic relations with Israel in 1993—a move that reflects a larger trend towards neoliberalism following the đổi mới economic reforms of 1986; the dissolution of the Soviet bloc following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989; and the eventual normalization of relations with the US in 1995. In the post-Cold War order, economic pragmatism replaced anti-colonial ideals. In 1994, Israel opened an embassy in Hà Nội, and in 2010, Vietnam reciprocated with its own embassy in Tel Aviv. Although Vietnam did vote in favor of an immediate ceasefire in Gaza at the United Nations General Assembly on October 27, in recent years Vietnam’s support of Palestine has been largely symbolic, far surpassed by its strong economic and military ties with Israel. It seems that Vietnam, therefore, has much to learn from the current Palestinian struggle for liberation.

As the daughter of a Vietnamese refugee displaced by war, I empathize with the Palestinian refugees displaced by the State of Israel—a bitter irony, given that Israel had been established as a haven for Jewish refugees, displaced by the Holocaust. As a recent mother, my heart goes out to all the Palestinian mothers who are forced to bury their own children—sons and daughters of all ages; those deemed “innocent” and those “guilty” of decolonial resistance. All are indiscriminately killed by Israeli military violence, which in turn is funded by US tax dollars. In my grief and mourning, I draw inspiration from the Vietnam-Palestine solidarity of the past. And I look forward with hope to the fulfillment of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish’s words from 1973: “In the conscience of the peoples of the world, the torch has been passed from Vietnam to us.”

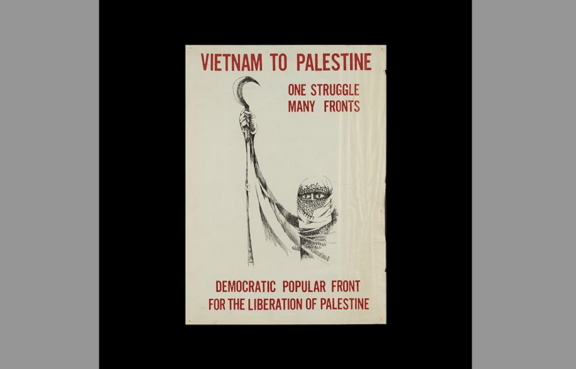

Cover image: The Palestine Solidarity Committee and Kamal Boullata, Vietnam to Palestine: One Struggle Many Fronts (circa 1970). Silkscreen. Buffalo, New York.