In a 2001 telephone interview with the New York Times from Vienna, Johann August Schülein, then president of the Freud Society of Vienna, said of Edward Said’s disinvitation, “A lot of members of our society told us—they can’t accept that we have invited an engaged Palestinian, who also throws stones against Israeli soldiers.”

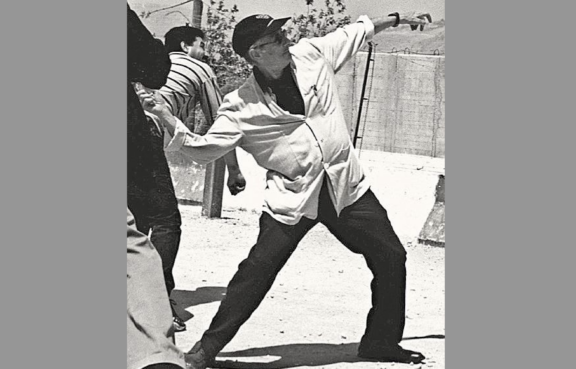

Twenty some years later, we know the story well: the Freud Society of Vienna cancelled their invitation to Palestinian intellectual Edward Said. What got him disinvited is a photograph we also know well: Edward Said, at the Lebanese border, throwing a stone at an Israeli Occupation Forces (IOF) guard tower. Subsequently, Jacqueline Rose, the director of the Freud Museum in London, extended an invitation to Said, resulting in his famous lecture (and later book) Freud and the Non-European.

Vienna’s disinvitation of Said certainly calls our attention to the limits of academic freedom in liberal democracies and provides a distinguished pedigree for enthusiastic and unabashed harassment and targeting of faculty, artist, activists, and students not only by outside pro-Israeli genocide advocacy groups but by presidents of North American and European universities.

The disinvitation shows what has become excruciatingly clear on university campuses and in psychoanalytic institutes since October 7, 2023: that the universal humanism of so-called liberal western democracies has no room for worlded humanity, let alone the defiant worldliness, of Palestinians.

Said has given us this concept of “worldliness,” of being in the world and of the world. This is not Spivak’s worlding that adeptly tracks how natives are placed in a Cartesian-nationalized world of the colonial author-administrator-mapmaker. It is more than Heidegger’s being in the world, and exceeds the lebenswelt imagined by Husserl. Worldliness is being of the world, a world of relationality with one another in a world of disavowals governed by coloniality, whiteness, cisheteronormativity, and capitalism, a worldliness excluded, negated, or denied by the ontologies mediated by the “Western ethnoclass of Man.”

Said’s worldliness communes with Edouard Glissant’s tout-monde or “mondialité.” It is a worldliness of a relationship to the land, ancestors, elders, and siblings that Gazans, and all Palestinians, inhabit, fight for, live for and, unfortunately, die for. The definition of worldliness demands us not to be abstract, but to be both poetic and concrete. It is a worldliness that millions in the street now are fighting for alongside the Palestinian people. Edouard Glissant teaches us to consider how poetic texts summon to the surface material realities and experiences in which we live together globally—in relation to a shared and co-created, albeit asymmetrical, world of exploitation, violence, and genocide, as is happening now in Gaza, and also, creativity, beauty, and defiance.

In North American and European universities, we are taught to consider the worldliness of people, objects, images, and texts. But this is a worldliness taught in a “dimensionless place,” as Glissant would say, a place that vacates it of its true social relations. We are seeing today, in the glaring shadow of genocide, that the university has space only for the abstraction (and monetization) of black, brown, queer, indigenous and working-class worldliness while having no space for the material realities of their being. There is no place of and for Palestinians in the disciplinary definition of academic worldliness especially on American, Canadian, and European campuses.

Glissant is clear in teaching us that mondialitié is not universalism (or globalization) but a worldliness that is determined by our relation to knowledge of the world; knowledge and experience constituted through communal, not individual, experience (or perhaps filiative experiences if we combine Said and Glissant). In this relation to the world, colonial, marginalized, and racialized subjects know a world that is otherwise imperceptible and illegible to—if not negated by—those in power and those of privilege, those who themselves have dragged so many to genocide, to the “abyss.”

For Said, texts, images, and objects are of their moment and place—but the fullness of their latent meaning only comes to the surface at any subsequent political moment. What becomes of Gaza in this photograph of Said? Of the moment of the stone, the stone in the hand of an Arab? Edward Said throwing a stone? Edward Said, the Arab and Palestinian in exile, whose family lived in exile in Egypt, Lebanon, and the United States, throwing a stone at Bab al-Fatima.

Edward Said throwing a stone at a border created through a secret agreement between colonial bureaucrats, forged at the same time that Arabs, who were promised independence, sided with France and Britain against their former Ottoman siblings. A border hardened by Fortress Israel. Edward Said throws a stone, perhaps two. His daughter, Najla, a playwright, and son, Wadie, now an eminent legal scholar, out of the frame. The foot and side profile of Lebanese Marxist militant and intellectual Fawwaz Traboulsi appear in the foregrounded margins of the photo.

In picking up a stone, a stone from the land (al-ard), Said revealed himself to be of that land. He is no longer “out of place” but of the place. The stone divulged that he was a native of that land. He held that stone, that soil. It held him. The image shows us that the stone was indistinguishable from him and indistinguishable from the worldliness of his theory. The stone showed that he was a Palestinian; Edward Said—stone in hand—revealed, much to the horror of the Austrians, Israelis, and their liberal imperialist accomplices, that he was of that land and of his theory.

Said had violated something. It was not throwing a stone at a Jew, which did not happen. It was not throwing a stone at an Israeli soldier valiantly defending against the Arab hordes, which did not happen. It was not Said throwing a stone at an empty Israeli watchtower over a border so saturated in violence.

Rather, Said picked up a stone, a stone from the land from which Palestinian and Lebanese crops and orchards are raised, and houses are built; crops, orchards, and houses that are either uprooted, demolished, or stolen and occupied by Israeli settlers, who claim, in a supreme act of colonial reality bending, that they—not Palestinians—are the native owners.

Said picked up a stone, a rock that may connect us to the Rock upon which the Dome is built in Jerusalem. He picked up a stone in a Lebanese village, Kafr Killa, only kilometers away from depopulated Palestinian villages such as Hunin. Its remnants existing under the current settler moshav Margoliot, Hunin’s Shiite population were terrorized through murder, sexual violence, and broken agreements to seek refuge across the colonial border in sibling villages like Kafr Killa in 1948, never allowed to return to their ancestral homes. With this rooted relationship between time and location, the rocks of the land that Said threw guide us to see how “Palestinian attention to the enormously rich sedimentation of village history and oral traditions potentially changes the status of objects,” thereby directing us, as Said teaches us, “to remainders of an ongoing native life and living Palestinian practices of a sustainable human ecology.”

This human ecology is not an empty abstract geological metaphor. Tiffany Lethabo King encourages us to consider the geological configuration of the shoal as an analytic that considers the intertwined spiraling striations of the geographical, geological, social, and historical. If Said’s critics of colonialism could be absorbed by the liberal university and psychoanalytic institutes, Said’s embodied defiance called attention to the geology and geography, the material landedness, of his theory, and to the normative social and intellectual practices and modes of being against which black and indigenous people are defined and which their presence disrupts. King quotes Seneca scholar Mishuana Goeman in thinking about “indigenous conceptions of land as connected [rather] than land as disaggregate parcels at various European-conceived scales” of accumulation. The photograph of Said forced his liberal admirers to uncomfortably witness that he, like the text and the critic, are “enmeshed in circumstance, time, place, and society—in short, they”—the photograph as text and Said as critic—“are in the world, and hence worldly.”

Said therefore violated what western academia thought it had agreed upon—a misreading of the worldliness of the Palestinian engaged intellectual. Let’s remember Schülein’s words: ”A lot of members of our society told us they can’t accept that we have invited an engaged Palestinian, who also throws.” This term, engaged (engagé) is not innocent, especially in a Europe well-familiar with Jean-Paul Sartre popularization of the term in the earliest volume of Les Temps modernes. Yet, in the context of Palestine, engaged intellectuals, like engaged literature, (al-adab al-iltizam) have a tradition that stretches beyond Ghassan Kanafani’s work. What is being told to Said is clear: remain in Sartre’s abstraction and distance yourself from Kanafani’s practice. Be an engaged intellectual exile, but never an engaged militant native.

Here, Freud’s the Psychopathology of Everyday Life is useful. The book asks us to consider the retraction of the Viennese Society’s invitation as structural, ordinary, and coming from the “privileged position” of the Board, which considered the decision so “slight” and “unobstructive” as to not warrant the sort of international attention that it gathered. A symptomatic reading of the cancellation steers us away from manifest explanations. The splitting, rather, is clear: Vienna wanted Said the intellectual without the worldliness of his intellect. They wanted a rational Said with texts but without their affective baggage.

They wanted the Palestinian exile, a Palestinian without a country, a Palestinian without Palestine. But the rock shattered their disavowal (Verleugnung); the rock tethers the Palestinian to Palestine, not as a metonym for, but the actual material grounding to the land. Like Glissant’s poem, the photograph is the unwinding back into its origins in the worldliness of place, space, and materiality.

In The Text, the World, and the Critic, Said’s admonition of theorists who ignore the material world and the ethics of a “critical consciousness” emerges most forcefully now in the time of genocide against the Palestinians, so readily disavowed by liberal academics and politicians. Critics reading texts (and theory) outside their worldliness “lose touch with the resistance and the heterogeneity” of the text, “blithely predetermining what they discuss, heedlessly converting everything into evidence for the efficacy of the method, carelessly ignoring the circumstances out of which all theory, system, and method ultimately derive.” Such disavowal is a form of collusion.

Both Said and Glissant, like Freud himself, were not driven by the cliché-but-functional binary-tension between theory and action; between the psyche and the social; the therapeutic space and the street; or between thought and its material dimensionalities. Glissant warns us: “thinking thought usually amounts to withdrawing into a dimensionless place where the idea of thought alone persists.” But for the engaged poet-intellectual—for the colonized poet-intellectual—“thought in reality spaces itself into the world. It informs the imaginary of peoples, their varied poetics, which it then transforms—meaning [that] in them, [thought] risks becoming realized.”

Said becomes what the martyred, intellectual Basil al-A’raj would call muthaqqaf mushtabak, an engaged intellectual, a militantly engaged intellectual. Said with the rock realized Said with theory. Said is of place but also of a collective moment of liberation. In this image and that moment, Said exists in different points of time and space, binding the Intifada of the 1980s with the al-Aqsa Intifada that was occurring at the very moment he was throwing the stone.

Unwinding this photograph further, de-condensing the dreamwork of this image back into the materiality of its moment, we recall that Said’s visit to the border occurred shortly after the liberation of South Lebanon, only months before, by the Lebanese resistance after twenty-two years of illegal Israeli occupation that resulted in tens of thousands of deaths of Lebanese and Palestinians, not to mention the illegal detainment and torture of thousands of men and women by Israelis and their Lebanese proxies.

The stone is the theory in the world. Said’s stone was both an homage to the Lebanese resistance and a promise to the Palestinian people that resistance will succeed.

But now, the fullness of the stone emerges in the worldliness of an image that confirms Edward Said as, yes, a mujahid, a fighter. The stone connected him with the “children of the stone” in the first Intifada and the resistance in Gaza fighting and living among stones from demolished homes. If Gaza is buried by the Israeli genocidal targeting of innocent life, every day exponentially by more and more rubble, by more and more stones, Said’s image is “a part of the social world, human life, and of course the historical moments in which they are located and interpreted.”

This “worldly” text is in community with other texts, other lives, other poetic relations, to borrow from Glissant, poetic relations of resistance and “psychic-political power” that burst forth from settler colonial “sites of death,” as Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian teaches us, to continually generate and re-generate a “collective psychosocial embodiment of everyday resistance.” The image and the event act in communion with the stones of Gaza as readily as the stones of generations of Palestinians resisting.

Just as Said picked up a stone as a part of his affiliative grammar of resistance inherited from Palestinians of the first Intifada, the resistance in Gaza and the West Bank now fight for liberation with Said as a filiative fixture of theirs. In thinking about this poetics of filial and affiliative relations that bind Palestinians across time, poetic relations that defy settler colonial time, the image of Said and his stone and the resistance of the Gazans re-congregate in the poem of celebrated Syrian poet, Nizar Qabbani, written in Beirut during the first Intifada.

يرمي حجرا

يبدأ وجه فلسطين

يتشكل مثل قصيدة شعر..

يرمي الحجر الثاني

تطفو عكا فوق الماء قصيدة شعر..

يرمي الحجر الثالث

تطلع رام الله بنفسجة من ليل القهر..’

يرمي الحجر العاشر

حتى يظهر وجه الله

ويظهر نور الفجر

..

يرمي حجر الثورة

حتى يسقط آخر فاشستي

من فاشست العصر..

يرمي يرمي يرمي

Throw a stone

The face of Palestine begins

It is shaped like a poem.

Throw the second stone

Acre floats on water, a poem of poetry.

Throw the third stone

Ramallah looks violet from the night of oppression.

Throw the tenth stone

Until the face of God appears

The light of dawn appears.

Throw a stone of revolution

Until the last fascist falls

Who fascisized this era.

Throw

Throw

Throw