The afrofuturist dystopic visions of Octavia Butler and Janelle Monáe tip on the tightrope of critical disability studies through the possibilities and limitations they reveal for post-human bodies. In Butler’s speculative fiction, disabled characters are gifted with transhuman abilities that are also impairments, making them hypervisible vulnerable targets of violence. Ableism in her texts is both challenged and reinforced by narratives that value interdependence yet punish through impairment. Genre defying musician Janelle Monáe enacts the same duality in her own work. In her first album-length project, Monáe explores cyborg identity and uses schizophrenia as a metaphor for freedom. She embraces her “crazy,” but her liberal use of the term, along with the equally contested appellation “schizo,” fosters an ambivalent reception to the disability justice content in her work.

Disclaimer: I love Janelle Monáe and Octavia Butler with a deep unbridled passion! That said, I’m not objective. I am interrogating my love by examining the elements of their work that are hardest to hold.

Octavia Butler

Science fiction writer Octavia Butler’s last novel before her untimely and strange passing capitalized on the resurgence of vampire lore in US popular culture. In Fledgling, the lead protagonist is Shori, a vampire with amnesia and unusually dark skin for her species. She is the result of genetic experiments designed to allow the Ina, as they call themselves, to live in daylight. She is a celebrated vision of the future and an equally hated marker of blood impurity.

Ina cannot assume the rugged individualism and autonomy that American culture values. Instead Ina society is interdependent, with trans-species relationships a necessity. Ina depend on their human symbionts, who are both lovers and blood supply, for survival — not only for food but also to help them stay out of the sun. In articulating the interdependence of vampires and humans, their shared emotional and physical care of one another, Butler offers a critique of racism and ableism in our world. In a moment of revelation, Shori notes that Ina need humans in ways humans do not need Ina, troubling Ina assertions of superiority over their human lovers. Butler queers the traditional master/slave colonizer/colonized narrative by exposing the multi-level dependence of Ina on humans, as well as troubling the idea that a nuclear and individual model of family is best.

Like a tomato with fish DNA, Shori is a controversial GMO success story. She is a being that calls into question who and what “Ina” means. This attempt to improve the living conditions of the species through daylight existence triggered racial purists to try to kill Shori and her family. One of the Ina responsible for Shori’s family’s death is sentenced to the traditional punishment of a painful dismemberment from which she will take years to recover. The character’s temporary disability constructs impairment as a punishment for bad behavior. It makes disability into a personal problem for those who have done something wrong, which in turn makes organizing for a more accessible world less important. Butler affirms the value of connection through interspecial relationships yet also works against interdependence through genetic modification.

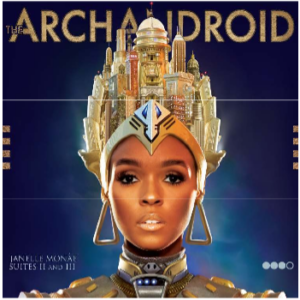

Like Butler, Janelle Monáe is interested in the transhuman possibilities of the body. Her alter ego, Cindi Mayweather, is an android from the distant future who does the impossible: falls in love with a human. This taboo animates a droid army to hunt and destroy her. Monáe’s album The ArchAndroid is the rock opera of Mayweather’s life on the run. As she attempts to remain true to her feelings, she struggles with the perceptions of the power structure who see her as wild, unstable, and crazy as she flouts the conventions of an ableist and human-centered world. Her body, like Shori’s, is a threat to the conventions of her community, troubling the meticulously maintained division of man and machine.

The ArchAndroid provides a window into Cindi Mayweather’s experience. The track “Faster” highlights her escape from the Droid Army. The invocation of the ableist slur “schizo” is supposed to be liberatory. She is talking about running for freedom, and schizophrenia is representative of the liberation she hopes to achieve. She sings: “I’m running, I’m running, running, running. I’m shaking like, shaking like a schizo.” Similarly, in the track “Alive” Monáe makes schizophrenia a metaphor for heightened consciousness. In reference to dance, she sings “That’s when I come alive, like a schizo running wild, that’s when I come alive, now let’s go wild!” If you’ve seen a Monáe live show, she does, as the kids say, “go off,” with dance moves that rival James Brown in their explosiveness. It is when Cindi feels most alive that society, in the form of medication, the droid army and institutional pressure, tries to squelch her boundary-breaking expression by forcing her to conform to an unanimated norm. Monáe’s critique is powerful but the sting of words that support ableism remains.

The video for “Tightrope” portrays Monáe and fellow institutionalized patients trying to break free of the repressive watchful eye of the powers that be through dance and song. She goes through walls and into the woods to escape those who would limit her expression. The video provides a visual critique of the ways in which disability is policed through showing the nurse’s attempts to medicate and thwart the revolutionary dance party of the patients. The audience is privy to the soul-crushing nature of the institution and we delight in the patients’ stolen moments of freedom of expression in dance, their powerful and uncontrollable hidden magic exposed.

For Butler and Monáe, transhuman disabled bodies offer possibility and freedom that simple humanity forecloses. Monáe’s use of disability as metaphor supports her alter ego’s search for a freedom in a world much like our own. However, by reducing disability to metaphor and by using ableist language, the real lives of disabled people are obscured. Butler’s depiction of Shori’s hybrid body serves as a flash point for eugenic impulse, allowing an investigation of the deep seated racial prejudices of our time. However, punishing characters through impairment makes disability into retribution, a just sentence for wrongdoing in an ableist world that doesn’t make accommodations for people who need them. Butler and Monáe open up conversations about disability that are messy and fraught, but they do so in arenas that traditional disabilities studies scholarship neglects.