Let me ask the terrible question: Could it be that all those perfectly straight, content-with-their-sexual-orientation-in-the-world, exclusive-heterosexuals really are (in some ill-defined, psychological way that will ultimately garner a better world) more healthy than (gulp…!) us? Let me answer: No way!1Delany, Samuel R. Dhalgren. 1974. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan UP, 1996. 720.

I first read this passage, buried deep in Samuel R. Delany’s mammoth 1974 science fiction novel Dhalgren, at an impressionable age. After days or weeks or months wading through a strange textual universe populated by social and sexual deviants whose connections and epiphanies and great sex I didn’t entirely understand but didn’t want to look away from, it occurred to me that this weird world might not be entirely separate from the one I inhabited when I looked up from my book. On the one hand, it suggested an “us” out there neither straight nor contented with sexual orientations and their meanings in the world. On the other, it offered a new view on ways in which my surroundings already failed to live up to the straight rendering of what “a better world” might be. Disappointments transfigured to electric possibilities.

Science fictions never present the future, only “a significant distortion of the present,” as Delany wrote in 1984.2Delany, Samuel R. Starboard Wine. Pleasantville, NY: Dragon Press, 1984. 177.But they also distort the present of anyone reading at any time, even the text’s own future. The contours of Dhalgren‘s disintegrating city belong to the wake of 1960s countercultures and social movements, to a sexual and racial moment whose history uninformed new generations of readers will learn as they read, even if they fail to recognize it. Sexual pleasure in Delany’s work links the past and present and lets a different future feel possible, even when it takes place within structuring limitations.

The protagonist of Dhalgren says: “it is not that I have no future. Rather it fragments on the insubstantial and indistinct ephemera of now.”3Delany, Dhalgren. 10The kinds of futures that Delany’s queer science fictions craft force us to recognize that living without a future is a not uncommon mode of being. The origins from which speculative imaginations lead us to deviate are not homogeneous, not predictable, and not easy to throw away. The people around whom Dhalgren‘s world centers are not the white male bodies on whose basis most of science fiction’s futures have been envisioned, but individuals from racialized populations more commonly figured as anonymous builders or human material backgrounded in dominant futurities. Queer characters have constant, unashamed sex that bears little relationship to reproductive futurism (even when individual sex acts are heterosexual). Yet in its speculative force, the writing remains committed to crafting and creating futures. They suggest how queer the world could feel even with a continual presence of racialized inequality, economic failure, and other material differences within alternative or futuristic possibilities. The queer future is not no future, but it is also not utopian, not a simple case of linear progress, of a world steadily getting better. Being led, through fictionalized speculation, away from the presumptions and regulations of dominant space and time opens up a different set of futures and worlds.

Queer worldmaking speculation doesn’t only happen in classic works of queer afrofuturistic postmodernism. But I am far from the only reader who fell into this particular novel and emerged changed by an explosion of speculative possibilities. Delany states that in writing Dhalgren his intention was emphatically not to provide “a sympathetic portrayal of the social problems of those who deviate sexually from the social norm,” but rather to “completely subvert … the entire subtext that informs a discourse of ‘social problems/sympathetic/sexual deviate/normal’ in the first place.”4Delany, Samuel R. The Straits of Messina. Seattle, WA: Serconia, 1989. 40.The novel doesn’t only insist that those who cannot fit themselves into the scripts of normative sex and sociality can be happy and functional despite their disadvantages; it rescripts the world to revolve around them. And so it has rescripted its readers. Novelist Nalo Hopkinson writes that “[w]hen [she] read Delany’s novel Dhalgren at about twenty-two years old, it blew [her] brain apart and reassembled the bits.”5Nelson, Alondra. “Making the Impossible Possible: An Interview with Nalo Hopkinson.” Social Text 20.2 (2002). 110.Critic Ann Weinstone discovered there “a companion world,” at “a moment in queer adolescence” of feeling “condemned to live alone.”6Weinstone, Ann. “Science Fiction As a Young Person’s First Queer Theory.” Science Fiction Studies 26 (March, 1999). http://www.depauw.edu/sfs/backissues/77/weinstone%20rev77.htm The novel even gave its name to an early online worldmaking experiment, DhalgrenMOO. I write shortly after returning from a feminist science fiction convention: a conflicted, complicated, and fabulously nerdy hub for people who are writing and otherwise imaginatively creating queer speculative futures and other dreams. In that physical space and its virtual corollaries as well as in the possibilities created in cultural production, the worldmaking work of conflicts, of sexual and social contact, of forms of life that unhinge expectations of the world as it is and of what it means to hope that we can make it better, take root in practices of living and thinking and writing that speculate queer worlds in all kinds of possible and impossible ways.

Queer speculations are neither obvious nor predictable, and are difficult to list. Tied down too clearly into individual or collective life narratives, they run the risk of resembling Dan Savage’s unimpeachably well-intentioned It Gets Better Project: an informative example of what queer worldmaking speculation is not. Inspired by a lament that “[m]any LGBT youth … can’t imagine a future for themselves,” Savage urged gay adults to “show” teens “what the future may hold in store for them” via online video (and now a book). Embedded in Savage’s marital bliss, in everyone’s hearty endorsement of the way their lives are turning out, is an insistence that growing up is all you need to overcome the social problems that being gay provokes: you too can be content with your sexual orientation in the world, can be sympathetic and normal. Just embrace your destiny as a cog in liberal, multicultural American society and overlook the rest of the world’s catastrophic failings. For scholars and activists seeking a different definition of a better or livable life, the speculative idea of making a queer world broadens the meaning of what better futures for queers can signify. I am interested in the experiences of encounters with queer speculative fiction, in the communities and subcultures and interactions that grow up around it, because they suggest how nonrealistic narratives expand what queer worlds can be, what they already are, offering more than a narrow and repetitive script where a queer child escapes from a restrictively heteronormative upbringing in order to slightly broaden the constraints against which the next generation will be doomed to chafe.

The continuing power of Delany’s science fiction demonstrates decades-old alternatives to the liberal progress narratives that seek to tell us “it gets better.” Instead, we can contemplate how it might get queerer and how queer things might always have been — without losing sight of imperatives to make individual LGBT lives better in the world as it is. Speculative fictions are one set of places to find prospects for worlds differently oriented toward norms and bodies. Before gay futures could be celebrated for their resemblance to straight ones, speculative fiction had begun to enact a queer set of futurities and possibilities that are still timely, still necessary, still to be surpassed. None of this is to say that Delany or any other writer has crafted a blueprint for the best possible queer-friendly world; a living engagement with speculative fiction’s futures doesn’t require that any one be perfect. It’s enough that there are dreamed-up worlds to tentatively, transformatively, joyfully step inside.

Alexis Lothian is a scholar of queer cultural studies, speculative fiction, and digital media. She is putting the final touches on her dissertation, Deviant Futures: Queer Temporality and the Cultural Politics of Science Fiction, and will receive her PhD in English from the University of Southern California in 2012. She is a founding member of the editorial team for Transformative Works and Cultures and has presented and published on science fiction literature and media and on fan video, including contributions to recent dossiers in Cinema Journal and Camera Obscura. Her website is http://queergeektheory.org.

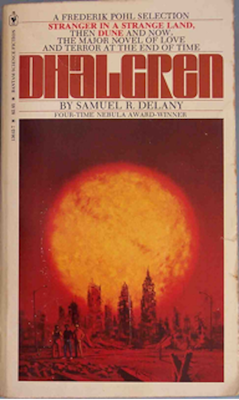

Top image: Dhalgren by Samuel R. Delany. 1974. Cover image by flickr user cdrummbeaks.