Serving as ASA President since the boycott has convinced me that U.S. national belonging is increasingly predicated on identification with Israel and disavowal of the violence made possible by its “special relationship” with the U.S.

In “Academic Freedom with Violence,” Roderick Ferguson and Jodi Melamed argue that in the backlash against the ASA, academic freedom has been wielded as a weapon to silence criticisms of Israel and exclude Palestinian suffering from public discussion. The promotion of academic freedoms for the privileged in Israel and the U.S. deflects from and delegitimizes critical knowledge about how the occupation limits the freedoms of Palestinians, academic and otherwise.

Ferguson and Melamed contrast this discourse of academic freedom with the actual investments of the field: Many members of the ASA study and engage social movements dedicated to different forms of freedom, including freedom from “capitalist exploitation, homophobia, sexism, racism and colonialism,” and such investments “[charge] us with bearing witness to Palestinian suffering and the suffering of other disfranchised communities.” Attacks on the ASA, they continue, often “exclude Palestinian oppression from the debate as meaningless to academic freedom.”

This account resonates with my experience with the media that covered the boycott. The New York Times misquoted me and took my remarks out of context but the Times declined, without explanation, to publish my opinion piece or even a letter to the editor. The Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post similarly rejected my opinion pieces without comment. Although academics routinely lament their seeming irrelevance to public debate, and while the media rarely give serious attention to academic freedom in other contexts (or to academia in general for that matter), suddenly condemnations of the ASA’s supposed crimes against academic freedom were viewed as imminently newsworthy while ASA witnessing to Palestinian oppression was not. To the extent that the construction of “the news” continues to represent an imagined community of U.S. nationalism, the exclusion of the plight of Palestinians from the category of newsworthiness casts ASA accounts of Palestinian suffering as irrelevant to national interests.

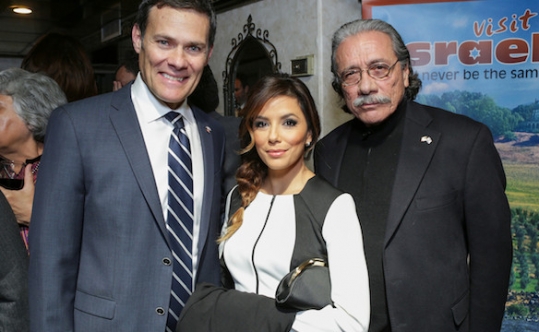

We can extend Ferguson and Melamed’s claims to comprehend contemporary models of U.S. democracy and national belonging that make support for Israel mandatory. Such support is increasingly promoted, for example, as a form of Latino assimilation to the United States. The American Jewish Committee and the Anti-Defamation League sponsor delegations of Latina/o journalists, corporate and media executives, and elected officials to Israel, while the Israeli Consulates in Miami and Los Angeles organize events to encourage Latina/o identification with Israel. The Los Angeles Consulate recently hosted a yacht party called “Fiesta Shalom at Sea,” whose guests included Latina/o celebrities and filmmakers such as Eva Longoria, Edward James Olmos, and Moctesuma Esparza. In his remarks at the party, Consul General David Siegel in effect argued that Zionism and Latino U.S. patriotism doubled one another: “Israel, like America is a land of opportunity and a multitude of cultures…We are both strong democracies, fueled and empowered by our immigrant populations, and strengthened by our diversity.” This celebration of the U.S. and Israel as immigrant nations and multicultural democracies suggests that Latina/o allegiance to the first should readily extend to the second.

In other accounts, the identification between Latinos and Israel is posited even more directly. For example, Mikki Canton, a Cuban-American lawyer who participated in a recent AJC delegation, explained that visiting Israel was “like looking into a mirror and seeing your twin…(Latinos and Israelis) share a love and respect for family, our culture and traditions. We celebrate our work ethic and economic prowess, yet as a people never forget who we are and where we come from.”

In order for Latinas/os to see their reflections in Israel, however, they must be encouraged to look away from the plight of the Palestinians. As reported by Max Blumenthal, in his 1993 book A Durable Peace, Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu argued that it was in the United States’ national interest to support Israel in order to prevent Latinos from comparing their situation to that of the Palestinians:

The United States is not exempt from this potential nightmare. In a decade or two the southwestern region of America is likely to be predominately Hispanic, mainly as a result of continuous emigration from Mexico. It is not inconceivable that in this community champions of the Palestinian Principle could emerge. These would demand not merely equality before the law, or naturalization, or even Spanish as a first language. Instead they would say that since they form a local majority in the territory (which was forcibly taken from Mexico in the war of 1848), they deserve a state of their own. ‘But you already have a state — it’s called Mexico,’ would come the response. ‘You have every right to demand civil rights in the United States, but you have no right to demand a second Mexico.’ This hypothetical exchange may sound far-fetched today. But it will not necessarily appear that way tomorrow, especially if the Palestinian Principle is allowed to continue to spread, which it surely will if a new Palestinian state comes into being.

By 2013, when Netanyahu had previously projected a potentially dangerous “Hispanic” predominance in the U.S. Southwest, he announced new Israeli public relations plans targeting Latinos. In the same news story about Netanyahu’s announcement, former Israeli Deputy Foreign Minister Danny Ayalon argued that “The United States is undergoing profound demographic changes, and it is important that Israel connect with the communities affecting the country’s character early in the process…Strengthening and preserving the relationship between Israel and the leaders of these communities guarantee the preservation of the strategic alliance with the U.S., which is vital to Israel’s security.”

The goal of Israel’s Latino outreach is thus to ensure that Latinos identify their interests with Israel because, it is suggested, Israel’s interests are ultimately in the national interests of the U.S.

By contrast, to call attention to violence against Palestinians is to invite attacks. After adopting the boycott—a nonviolent, First Amendment-protected tactic with a distinguished history in the great 20th-century movements for social change—ASA members were rhetorically excluded from rational discourse (our fields of study, especially ethnic studies and queer studies, were ridiculed), from democratic society (we were called “Nazis” and “fascists”), and ultimately from the nation. In addition to hate mail sprinkled with homophobia, anti-black racism, and Islamophobia, I received emails calling me a “wetback” and telling me to “go back to Mexico.”

Such messages suggest in the crudest and most reductive ways how Zionist multiculturalism may depend upon aggressive forms of abjection, and an aggressive turning away from the consequences of the occupation. The backlash against the ASA is thus part of a larger struggle over the meaning of freedom, which is in danger of being redefined to mean freedom from witnessing Palestinian suffering.

Curtis Marez is Associate Professor of Ethnic Studies at UC San Diego and the President of the American Studies Association.

(Photo credit: Jewish Journal)