The conceptualization of decolonial aesthetics[i] is fairly recent, however its points of departure — the epistemic shifts that have been challenging coloniality in the artistic and cultural practices of the Global South — are as old as the colonial system. The defiance of colonialism in Vodou dance and rituals, which in Haiti ultimately led to the first successful enslaved people’s revolution, is a splendid case in point.

What decolonial aesthetics does is to connect these legacies and their current displays to the decolonial analytical model. BE.BOP 2012. Black Europe Body Politics[ii] introduced this theoretical approach to the visual arts in Europe and the African continent with a wide spectrum of screenings.[iii]

BE.BOP 2012 at Ballhaus Naunynstrasse

Photo by Wagner Carvalho

In the process of organizing BE.BOP 2012, I conceptualized the diasporic as a specific approach to decolonial aesthetics with the purpose of outlining the particularities of certain continental Black European experiences. This work in progress led to the conceptualization of “Afropean decolonial aesthetics.” What follows is a mapping of the field of diaspora aesthetics that is then put in relation to the theoretical discussion of the “Afropean” and the decolonial.

The modernity/coloniality research program was inspired by the groundbreaking contribution of Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano. It offers a tool to dismantle the continuities of colonialism after formal decolonization. At the same time the program defines modernity as a rhetoric inseparable from the logic of coloniality (Mignolo 2008). This explains the systematic exploitation of entire populations in the name of “progress” and “civilization.” The analysis of the inseparability of these processes gives birth to the modernity/coloniality research agenda. Decolonial thinkers consider postcolonial studies to be limited in scope since, in addition to omitting this inextricability, their genealogy is anchored in rather provincial theories of (post)modernity based largely on Eurocentric historical and intellectual genealogies.

There are several conceptualizations of diaspora aesthetics in postcolonial studies within what R. Radahkrishnan (1991) calls “The Age of Diaspora.” Kobena Mercer has published extensively on the subject since the 1980s. Other conceptual contributions include Alexander Weheliye´s “Afro-diasporic aesthetics” (2005:324) and Krista Thompson´s “African diasporic forms” (2011:38). These concepts and theoretical approaches share a common thread with the seminal essays on diaspora and cultural representation by Stuart Hall. They also share a dialogical stamina in their analysis. The authors systematically choose to articulate their ideas by focusing on specific cultural practices rather than trying to establish yet another abstract universal. In other words, these are situation-specific conceptualizations, comme il faut. In the case of Thompson, the focus is given to the social status performed in the hip-hop-inspired prom rituals in the Bahamas. Weheliye, “accompanied” by W.E.B. Du Bois, Walter Benjamin, and Ralph Elllison, introduces “sonic Afro-modernity” as an indicator of the disjuncture between sound and source exemplified by “Souls.”

In Mercer´s paradigmatic reflections on diaspora aesthetics, the moving image plays a relevant role. Many of the works presented and discussed during BE.BOP 2012 share with the early Black British filmmakers analyzed by Mercer the confounding of stereotypes and the displacement of common assumptions of an essentialized Black identity. What differentiates the works of BE.BOP 2012 from those studied by Mercer is a rather bizarre element: the fact that Black filmmakers in Britain did not have to “prove” that colonialism and imperialism actually “happened.” Nor did they have to “prove” their “relevance,” in contrast to the case of The Netherlands, where it is thought that colonialism and imperialism happened “so long ago” that they are treated as ultimately irrelevant.

Afropean decolonial aesthetics contributes to current conceptualizations of diaspora aesthetics by illuminating the ways diaspora creators address the occlusions concealed by modernity that hide the dirty job of colonality. In this sense, our presence in what Quinsy Gario has described as “modern art plantations” (and I paraphrase as “the art plantations of modernity”) is neither tangential nor incidental. It is indeed, this inescapable plantation-system mentality — superbly argued by Antonio Benítez Rojo in La Isla que se Repite (The Repeating Island: The Caribbean and the Postmodern Perspective, 1998) — that artists from the Caribbean and other Black diasporas have chosen to challenge. They challenge its coloniality of knowledge and being. They create possibilities of sensing that strip the hegemonic “supremacy” of modernity. The video-collage Other by Aboriginal-Australian artist Tracey Moffatt is a masterpiece in this regard.

Tracey Moffatt

Other, 2009

7:00, sound

Courtesy of the artist and The Momentum Collection

Afropean decolonial aesthetics assumes the Caribbean diaspora as organically implied in Black and/or African diaspora in Europe. There is a vast global bibliography on diaspora studies and, particularly in Europe, situation-specific re-semanticizations of the term are mushrooming all over the place. For the sake of clarity, I will quote the definition of Agustín Lao Montes of the African Diaspora since it feels closer to my own experience as a member of the Caribbean Diaspora:

If the world-historical field that we now call the African diaspora, as a condition of dispersal and as a process of displacement, is founded on forms of violence and terror that are central to modernity, it also signifies a cosmopolitan project of articulating the diverse histories of African peoples while creating translocal intellectual/cultural currents and political movements.

(Lao Montes 2007:55).

The “decolonial” in aesthetics substantiates the notion that we are and always have been part of modernity. This is why our strategies of re-existence (Albán Achinte 2010:20) are analyzed as an integral part of modernity; instead of defining ourselves as “other modernities,” we call ourselves “decolonized coloniality.”

The following quote by Stuart Hall is illustrative of a key contestation of decolonial thinking and aesthetics with respect to postcolonial and cultural studies:

Thinking about my own sense of identity, I realize that it has always depended on the fact of being a migrant, on the difference from the rest of you. So one of the fascinating things about this discussion is to find myself centered at last. Now that, in the postmodern age, you all feel so dispersed, I become centered. What I’ve thought of as dispersed and fragmented comes, paradoxically, to be the representative modern experience! This is “coming home” with a vengeance!

(Stuart Hall in Mercer 2005:316)

From the decolonial perspective, we have never abandoned “home” (coloniality). The process of decolonization of our minds involves a realization of this fact. We have always been here as the hidden side of modernity, therefore our presence is self-explanatory. Self-agency, on the other hand, is something that decolonial thinking and doing shares with Hall´s dictum, since ultimately our recognition in the mirroring mirages of modernity unites us in solidarity. Furthermore, Afropean decolonial aesthetics embraces Hall´s “burden of representation” as a most welcomed gift: the gift of self-awareness, the gift of mental, sensing, and aesthetics decolonization. Just as Hall describes, during BE.BOP 2012, we became centered in our own experiences within a Pan-European context. We talked between ourselves, to ourselves, about ourselves; it was a banquet of identities. The so-called postracial, postidentity, or post-Black eras were oxymorons in our vocabulary.

Teresa María Díaz Nerio

Hommage à Sara Bartman, 2007

Performance 40′, Video 5′, no sound

Courtesy of the artist and Art Labour Archives

At the Berlin event, there were two-hour screening sessions every morning, followed by roundtable discussions on Decolonial Aesthetics and Aisthesis, (Black European) citizenship, anti-Blackface activism, fashion and womanhood in Africa, the Berlin-Africa Conference, the Herero Nama Genocide, and colonial amnesia in Germany and Scandinavia.

Artists, activists, and scholars shared their knowledge on equal terms during the rich and diverse discussions. Film and video art were equated in status; the industrial character of the former shared the same screening format and set-up as the latter. Performance art was discussed at a postmigrant experimental theatre space. The scholarly work of theoreticians was discussed at an extra-academic space. Activists were given plenty of space to display their campaigns and spread their messages. This event created a paradigm shift in decolonial sensing, thinking, and doing. The many layers of this conversation are documented in the evaluations of the participants, collected in really long essays or in short and moving statements. They have been published in the last dossier of IDEA: Arts + Society No. 42.[iv]

The pervasive colonial amnesia in Germany, The Netherlands, and Scandinavian countries skillfully illustrates a Pan-European scenario of the denial of coloniality. The denial of the systematic involvement in the financial network of the transatlantic enslavement trade and later in the Berlin-Africa Conference (1884-1885), are just two examples.

Since artists in different European locations thoroughly engage with these historical vacuums, my choice to connect them with my own curatorial praxis responds to what Erna Brodber has described as the “Continent of Black Consciousness,” but from the situation of living in Europe and not in the Caribbean. Therefore, the particularization of “Afropean” is meant to signal the emergence of Black Consciouness in Europe from a Pan-Africanist perspective.[v]

During BE.BOP 2012, our multiple dialogues were focused on the works of artists, thinkers, and activists inhabiting the Continent of Black Consciousness in Africa (Simmi Dullay), the Caribbean and African Diaspora in Europe (Teresa María Díaz Nerio, Jeannette Ehlers, Quinsy Gario, Ylva Habel, Grada Kilomba, Adetoun Küppers Adebisi, Michael Küppers Adebisi, Ingrid Mwangi Robert Hutter, David Olusoga, Minna Salami, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Robbie Shilliam, Jean-Marie Teno and Emeka Udemba), and Australia (Tracey Moffatt and Sumugan Sivanesan).

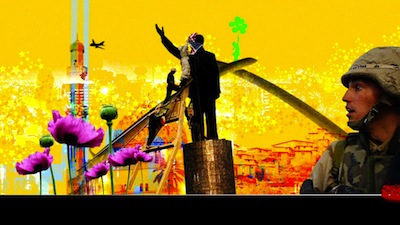

Sumugan Sivanesan

A Children´s Book of War. A [Not So] Secret War: Terra Nullius and the Permanent State of Exception, 2010

1:46, sound

Courtesy of the artist and The Momentum Collection

The decolonial in Afropean decolonial aestethics acknowledges our common struggle against coloniality materialized in chilling examples of systematic racialization and prosecution of people of African descent in Europe, which will be discussed further on. Together in this decolonial journey of thinking mind and sensing decolonization, we are not only demanding retribution for the colonial legacies in Africa, we are also outlining the continuities of these legacies in coloniality, that is in colonialism without colonies.

European coloniality is present in a brand-new institution: Frontex,[vi] an external and internal borders program, founded in 2005, with the fastest-growing budget in the European Union, a European Union that was first known and conceptualized as inseparable from (the exploitation of) Africa and therefore named by its founders as “Eurafrica” (Hansen and Jonsson 2011). Indeed, there are irrefutable historical continuities between the Berlin-Africa Conference (1884-1885), the original Eurafrica (European Union) project, and current “mappings” of migration routes in the African Continent. This border externalization “initiative” could be defined as a de facto “cartographic war” against Africa, and adds up to the relevance of “Afropean” as a tool to reveal the current entanglements of coloniality in Europe. “Afropean” announces these realities and goes beyond mere reflection by inverting the order of its two components. They say “Eurafrica” and I say “Afropean,” from our own “community tale.”[vii]

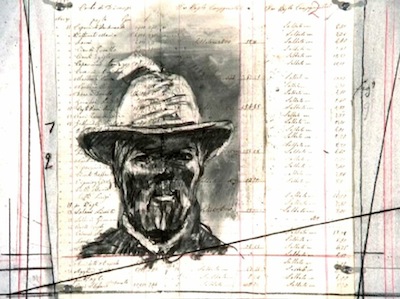

William Kentridge

Black Box/Chambre Noire, 2005

22:00, sound

Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

Paradoxically, the African presence in Europe is older than in the Americas. The (still-contested) eight hundred years of African occupation of the Iberian Peninsula is a case in point. And Négritude, the epigram that contributed to the liberation of the African continent in the so-called Short Century, was invented in the 1930s in Paris, where one of the five European Pan-African Congresses was also held (the first Pan-African conference took place in London, in 1900).

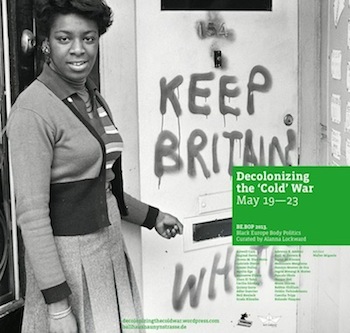

The recent edition of BE.BOP 2013, entitled “Decolonizing the Cold War,“[viii] will be dedicated to exposing how the Black Body as a space of dignity, power, and beauty permeated the radical imagination of artists and thinkers in Europe beyond racial divides. We approached in performances, screenings and roundtable presentations the legacies of the Black Panthers. A highlight of the event was the presence of two former Black Panthers from the Caribbean Diaspora in England, Barbara Gray and Neil Kenlock, the official photographer of the movement.

Another ground for the pertinence of “Afropean” in relation to diaspora aesthetics and diaspora studies in general is that, unlike in the US, the UK, the Caribbean and Latin America, the Black Diaspora in continental Europe cannot comfort itself with being an accepted community within the nation at large, not even a pathologized one. In this regard, the “Afropean” brings the Black or Afro- community into a particular resonance with respect to diaspora aesthetics. It has a related but distinct place vis-à-vis hegemonic, US-focused, academic discourses, and also in relation to Black British cultural studies á la Hall.

Likewise with regards to its demarcation within Diaspora Studies, “Afropean” (in relation to decolonial aesthetics) clarifies the particular challenge of establishing the fact that colonialism actually did happen in the first place. In the Americas (where the term “decolonial aesthetics” was coined) this is self-explanatory to the point of absurdity; however in our European realities it is absolutely the opposite. “Afropean” is meant to optimize the dialogical understanding between two processes of mental decolonization with common objectives and a shared African and European colonial legacy, but very different canonical historiographies. As previously argued, the systematic historical erasure of colonial legacies after the Berlin-Africa Conference (1884-1885) is exemplary of this situation. To give a revealing example, there are no monuments in Berlin that commemorate this outlandish event.

Additionally, “Afropean” is also aimed at expanding awareness of the alarmingly growing Afrophobia of continental Europe.

Quinsy Gario

Zwarte Piet Is Racisme, 2010-2012

Peformance campaign

Photo by Brett Russel

Courtesy of the artist and Art Labour Archives

As Quinsy Gario so cheerfully exposes in his performance campaign, Zwarte Piet Is Racisme,[ix] a demeaning caricature of Blackness is valued as an unchangeable “innocent” cultural heritage in The Netherlands, utterly “unrelated” to colonialism, which, as we know, “happened too long ago to even matter anymore.” Blackface is also institutionalized in Germany as a “respectable” theatrical tradition. The infamous Swedish cake[x] and countless alarming examples of racial profiling, police harassment, and random murders of African immigrants in Greece are just the tip of the iceberg.

Adding to these symptomatic examples, I must admit that in spite of consistently trained political awareness, the hate speech against and persecution of Somali communities in Sweden, the deaths under police custody in Germany, the legal proscription of “anti-white” racism in France, the kidnapping of legal residency documents from Afro-Spanish citizens by the police, and a long list of unthinkable acts, still take many of us by surprise. Black Europe and the African diaspora are indeed living extremely dangerous moments of coloniality and need as much solidarity as we can humanly get.

The pertinence of Afropean decolonial aesthetics in relation to current debates on identity issues is made evident by a revealing statement of curator and writer Simon Njami:

It has always been a matter of regret to me that the history of certain parts of the Caribbean has been obscured. That is not just the fault of the whites. Both whites and blacks have adopted a fairly ambiguous attitude to this topic. I can quote Césaire from memory who said, in talking of the Caribbean, that its people would never be capable of transforming their situation until they had admitted all aspects of their history.

What does this history consist of? Slavery, of course, and Africa. But every time I visit the region I am struck by the glaring omission of that continent in artistic debates. It is not a question of agitating on behalf of the Negroes, i.e., Africans, as in the early days of Négritude. Rather it is about incorporating the developments in the African continent as an integral part of their own history. There are few links, few projects aimed at bringing these two parts of the world closer together even though that might be where the future lies. We are told that history is written by the victors. But are we still tackling the debate in terms of conquerors and the conquered?

(Simon Njami interviewed by Jocelyn Valton 2012:139).

How does this particular quote reveal certain key contestations of decolonial aesthetics and how does Afropean decolonial aesthetics challenge its presuppositions? Do we need to nurture the widely theorized Caribbean Caliban (Fernández Retamar 2000) approach of using the decolonial analytical model as a tool to question the coloniality of aesthetics? Should we speak of the aesthetics of coloniality as an aspect of the coloniality of knowledge and being? Should we focus our energy entirely on the strategies of re-existence of what artistic practices are doing today in modernity´s art plantations? Or should we do all of that at the same time?

One can think of delivering a very simple response to the first part of Njami’s quote. The fact that you have not read, seen, or heard about something does not necessarily mean that it does or did not happen. It is indeed the inevitability of misinformation or disinformation among the different contexts of the Black, African, and Caribbean Diasporas that demand from those of us engaged in its conceptualization, both as theoreticians and as facilitators, to actively pursue the filling of those gaps and not to simply expose or complain about them. The second part of this symptomatic statement by Njami regarding “tackling the debate in terms of conquerors and the conquered” is lapidary. Indeed, for decolonial aesthetics it is a matter of principle, in its most literal meaning. Its departure point is to systematically unveil the rhetoric of the conquerors (European modernity = civilization) in the logic of coloniality (any art produced elsewhere outside Europe is “primitive” or just a mimicry of the “universal” essence of European art).

Obviously, Simon Njami is unaware of how the imperial imagination persists by portraying his presence as Diaspora thinker in the art plantations of modernity. As a reference from the inexhaustible list of coloniality, I offer him the following description of Documenta 12 and a quote by its co-curator, Roger Buergel:

The rainy summer was responsible for taking away the excitement of Documenta 12 that finished last Sunday, according to exhibition director, Roger Buergel: “The life outside the exhibition halls could not flourish. This meant that the ideal atmosphere, the liveliness could not be nurtured”. The arts need warmth: “This is why Greece is the origin of civilization and Africa that of mankind.”

(Der Tagesspiegel, 24.09.07. p 25).

It is imperative to remind Njami that Hegel made his epistemic division of Africa (Taiwo 1997) at the same time that the first German Protestant colonizing mission was established on the continent (1829). In this sense, we could interpret his Philosophy of History as a formidable public relations campaign in favor of European colonization. Likewise, Walter Mignolo (2010-2012) has established the inextricable connection between Kant´s racialization discourses (Eze 1997) and the invention of an aesthetics that determined that only white Europeans were capable of attempting and understanding the sublime. Hegel´s infamous dictum on the ahistorical character of the African continent is in this sense a mere continuation of Kant´s “wildly” imaginative categorizations.

In Marcus Mosiah Garvey´s Pan-Africanism we are commanded to decolonize our minds. During a speech in Nova Scotia in October 1937, which was later published in his Black Man magazine, he directed us to emancipate ourselves from mental enslavement. This legendary authority has been masterfully paraphrased by Bob Marley in his “Redemption Song” (1979). I see that Afropean decolonial aesthetics comply with Garvey´s prophecy. I see it in every line of my writings and in every moment of solidarity between the Diasporas that I have experienced since my own mental decolonization started (Haiti 1994, to be precise). Therefore, and in order to conclude by answering again the last question posed by Njami–“Are we still tackling the debate in terms of conquerors and the conquered?”–I respond: Indeed we are, in fact this is exactly what Afropean decolonial aesthetics is about. It is about demanding epistemic accountability and retribution from the perpetrators and current inheritors of white privilege in modernity´s art plantations while at the same time celebrating ourselves in our mutual recognitions. We are here because we have ALWAYS been here but it does not necessarily mean that we want to fit into the white Cube, we are here as Quinsy Gario tells us:

. . . to talk

about our work

about our locations

about our bodies

about ourselves.

The selves that move

in and out of sight

between the pauses

of time and space

and beyond

the notion of what is slightly

unsound.

Top image: Jeannette Ehlers / Black Magic at The White House, 2009 / 3:46, sound / Courtesy of the artist and Art Labour Archives. https://vimeo.com/25062988.

APPENDIX

Between 2011-2012 decolonial aesthetics in the context of BE.BOP 2012 was discussed for the first time at:

Goldsmiths University of London

http://mars.gold.ac.uk/politics/events/headline,34285,en.php

Matadero Madrid

http://www.videoartworld.com/data/bulletins/Imagery-Affairs-during-ARCO-Madrid.html

Documenta 13

http://andandand.org/events/five-decolonial-days-in-kassel-transforming-our-realities-turnhalle-4/

Dutch Art Institute

http://dutchartinstitute.eu/page/1635/shift-in-my-thinking

Kade Museum

http://framerframed.nl/en/projecten/decolonial-aesthetics-and-european-blackness/

Transart Institute Berlin

http://transartinstitute.wordpress.com/2011/07/

Universidad de Cádiz

The Bioscope Johannesburg

Kwa-Zulu Natal Arts Society

http://kznsagallery.co.za/events/2012/April/black_europe_body_politics_film_screening.htm

National Arts Gallery of Namibia

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albán Achinte, Adolfo (2010). Comida y colonialidad. CALLE14, Bogotá, Colombia, volumen 4, número 5, julio -diciembre de 2010.

Benítez Rojo, Antonio (1996). The Repeating Island. Durham: Duke University Press.

Brodber, Edna (1994). Louisiana. A novel. London: New Beacon Books.

Clark Hine, Darlene; Keaton, Tricca D.; Small, Stephen (Eds.) (2009). Black Europe and the African Diaspora. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Eze, Emmanuel Chukwudi (1997). The Color Of Reason: The Idea Of “Race” In Kant Anthropology. In: Postcolonial African Philosophy. Eze, E. C. (Ed.). Lewisburg: Bucknell University.

http://blogs.umass.edu/afroam391g-shabazz/files/2010/01/Eze-on-Kants-Race-Theory.pdf

Fernández Retamar, Roberto (2000). Todo Calibán. La Habana: Fondo Cultural del ALBA.

Gario, Quinsy (2012). Nets Have Many Holes. Amersfoort, The Netherlands.

http://framerframed.nl/en/dossier/nets-have-many-holes/

Ha, Kien Nghi / Roth, Julia (Curators) (2012). Metro. Facetten der asiastisch-deutschen Diaspora in Berlin. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung.

Hall, Stuart (1989). Cultural Identity and Diaspora. Framework (no. 36). http://www.rlwclarke.net/Theory/PrimarySources/HallCulturalIdentityandDiaspora.pdf

___________ (1996/2005)Critical Dialogues in Popular Culture. Edited by Morley, David and Chen,Kuan-Hsing. London and New York: Routledge.

http://wxy.seu.edu.cn/humanities/sociology/htmledit/uploadfile/system/20110213/20110213135536108.pdf

Hansen, Peo /Jonsson, Stefan (2011): Bringing Africa As A ”DOWRY To Europe”, Interventions, 13:3, 443-463

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2011.597600

Gario, Quinsy (2012). Nets Have Many Holes. Amersfoort, The Netherlands. http://framerframed.nl/en/dossier/nets-have-many-holes/

Lao Montes, Agustín 2007: Hilos Descoloniales. Trans-localizando los espacios de la Diáspora Africana. Tabula Rasa. Bogotá Colombia, No. 7: 47-79, julio-diciembre 2007.

Lockward, Alanna (2012). Decolonial Diasporic Aesthetics. Black German Body Politics.

http://blackeuropebodypolitics.wordpress.com/decolonial-diasporic-aesthetics/

Lorde, Audre 1984: Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference. In: Sister Outsider, Los Angeles: Freedom, P. 114-123.

Mercer, Kobena (2005). Diaspora Aesthetics and Visual Culture. In: Black Cultural Traffic: Crossroads in Global Performance and Popular Culture. Justin, Harry & Kennell Jackson, Iam (Eds). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. 141-161.

___________ (1994) Recording Narratives of Race and Nation. In: Welcome To The Jungle: New Positions in Black Cultural Studies. London: Routledge. 69-96.

Mignolo, Walter (2012 A). Decolonial Aisthesis and Other Options Related to Aesthetics. In: BE.BOP 2012. Black Europe Body Politics. Lockward, Alanna, Mignolo, W. Eds. Berlin: Ballhaus Naunynstrasse.

http://blackeuropebodypolitics.wordpress.com/catalogue/

___________ 2008. Delinking. The Rhetoric of Modernity, the Logic of Coloniality and the Grammar of De-Coloniality. North Carolina: Duke University Press.

http://townsendcenter.berkeley.edu/pubs/De-linking_Mignolo.pdf

Ngozi Adichie, Chimamanda (2011). Speech at SPUI25 in the 3th debate in the Narratives for Europe – Stories that Matter series.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-YEWg1vIOyw

Patterson, Tiffany Ruby & Kelley, Robin D. G. (2000). Unfinished Migrations: Reflections on the African Diaspora and the Making of the Modern World African Studies Review, vol. 43, no. 1, pp. 11-46.

Santiago-Valles, Kelvin A. (2003). “Race,” Labor, “Women’s Proper Place,” and the Birth of Nations: Notes on Historicizing the Coloniality of Power. The New Centennial Review, Volume 3, Number 3, Fall 2003, pp. 47-69. Michigan State University Press. DOI: 10.1353/ncr.2004.0010

R. Radhakrishnan (1991). Ethnicity in The Age of Diaspora.Transition No. 54 (1991), Indiana University Press pp. 104-115

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2934905

Taiwo, Olufemi (1997). Exorcising Hegel’s Ghost: Africa’s Challenge to Philosophy. African Studies Quarterly. Issue 4 (Religion and Philosophy in Africa).

http://www.africa.ufl.edu/asq/v1/4/2.htm

Thompson, Krista (2011). Youth Culture, Diasporic Aesthetics and the art of Being Seen in the Bahamas. African Arts. Spring 2011. http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/afar.2011.44.1.26

(downloaded 20.10.2012)

Valton, Jocelyn (2012). Art in the Caribbean. A Way to Defy History. Jocelyn Valton in Conversation with Simon Njami. In: Hoffmann, Nancy / Verputten, Frank, Eds. (2012). Who More Sci-Fi Than Us, contemporary art from the Caribbean. Exhibition catalogue, Kunsthal Kade. Amersfoort: Kit Publishers. 134-141.

Weheliye, Alexander (2005). The Grooves of Temporality. Public Culture Durham: Duke University Press. 17(2): 319-38. http://www.english.northwestern.edu/people/documents/weheliye3.pdf