In Esopus, a small town in upstate New York, a monument dedicated to Sojourner Truth was erected in 2009 (fig. 1). Truth was born in the area then known as Swartekill, some time in 1797, and lived in bondage in Ulster County for three decades. The memorial depicts Truth as an enslaved child to serve as a reminder of the institution of slavery in New York, according to a member of the commission tasked with putting it together. Truth self-emancipated in 1826 and won her son’s freedom in court against her former enslaver two years later, the first instance of a Black woman successfully suing a white man in United States history. Truth was a renowned abolitionist, fervent women’s rights advocate, and accomplished public speaker. She recruited Black troops for the Union Army during the Civil War. She lobbied for reparations for formerly enslaved Black Americans. What are the implications, then, of casting Truth actually and figuratively into bondage?

Public monuments are by necessity conservative because they are meant to stand unchanged; therefore, they are rarely able to tell a complicated story about past events or people. How we depict historical Black figures in public spaces is important because it either reinforces or undermines cultural stereotypes about Black lives now. Reducing Truth to an enslaved child in the cultural narrative is thus an indirect but still pernicious form of historical erasure; her full life and achievements are irrelevant to the story told by and through this monument to her. Writer Saidiya Hartman calls this a failure to look outside a “racial calculus” of enslavement. While the intention to humanize the figure by depicting her in girlhood is clear, important parts of Truth’s life and work are lost to the viewer. But by positioning the Sojourner Truth memorial within a larger conversation around commemorative gestures, we can better understand how a lack of imagination keeps us from seeing a Black figure beyond the reductive narrative of supremacy. Doing so can even help us understand, from a historical perspective, how we misrepresent Black life today and continue to devalue it.

Contemporary monuments must often play two roles: engage the public in a larger dialogue about site-specific histories and correct a biased historical record. The Sojourner Truth memorial in Esopus fails to achieve the latter, reinforcing her oppressed status and thereby diminishing her power in our collective memory. The monument’s sculptor, New Paltz-based Trina Greene, depicts her around age twelve, cast in bronze. The artwork stands about five feet and six inches high and is installed on a small granite plinth. The girl is barefoot with her right heel planted firmly in front of her left foot mid-stride. She carries two jugs—one of liquor and the other full of molasses—in her left hand and under her right arm at her hip (fig. 2). The hatched markings on her dress lend it the appearance of coarse material, and the garment’s open back exposes deep scars cut into her shoulders (fig. 3). As noted by reporters covering the memorial’s unveiling ceremony, children reached out to touch the detailed grooves on the girl’s back. The research committee, comprising local historians, scholars, public officials, and citizens, was instrumental in unearthing Truth’s childhood story and establishing locations as sites of historical significance. Looking at this monument to her, however, it is hard to see what the woman was able to accomplish in her lifetime. We focus instead on the physical marks of bondage: her bare feet, coarse dress, and scarred body. This means that more than a century and a half after emancipation in the United States, the Black figure is still effectively subjugated in the historical imagination.

Because we still cannot imagine what freedom looks like, we do not have the vocabulary (visual or otherwise) to define it, let alone to begin to articulate it in public space. And the commemorative artistic tradition does not offer a comprehensive visual vocabulary to begin. This problem isn’t new: art historian Kirk Savage’s work shows us how the imagery of enslavement in nineteenth-century public monuments maintains the subjugation of Black people in the American narrative. In his book Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves, Savage argues that the “logic of commemoration” constrained the imagery of emancipation in public monuments. While sculptors attempted to innovate a centuries-old genre that traditionally idealized the European form, most could not successfully imagine what would “speak to what the nation was in the process of becoming.” This perennial challenge is due in most part to the abandonment of the goals of Reconstruction in the crucial period after the Civil War.

Looking back, much of the nineteenth-century imagery meant to commemorate the hard-won fight for freedom depicted Black figures in poses that deny them their agency. The most common representation modeled an antislavery medallion known for its phrase “Am I Not a Man and a Brother,” showing a supplicant Black figure to elicit sympathy for the abolitionist movement. This popular pose reinforced the stereotype of Black men and women as helpless and childlike, a stereotype that abolitionists and anti-abolitionists alike used to support their causes. Another prevailing image of emancipation that made its way into the postwar consciousness was an enslaved Black man kneeling before a white savior figure, usually Abraham Lincoln. One of the better-known public monuments depicting this relationship is the Emancipation Memorial in Boston, which the city’s arts commission voted unanimously to have removed in July. The monument, designed by Thomas Ball and installed in 1879, creates a physical hierarchy that strengthens a social one. The manacled and half-clothed man, whose face turns up toward Lincoln’s outstretched hand, forever relies on the emancipator’s beneficence to imagine freedom.

Societal expectations of ownership over Black people strengthen a current sense of entitlement to view those people in all instances and leads to their ongoing surveillance and policing. If we compare nineteenth-century monuments to modern-day memorials to Black Americans, questions about representation and purpose continue to bubble to the surface. There has been a strong push in recent years to circulate media of murdered Black Americans in life, not to depict their deaths. But the desire to raise awareness of the everyday brutality and state-sanctioned violence against Black Americans in the public consciousness cuts both ways, no matter how those Black Americans are depicted. Artist Amy Sherald’s portrait of Breonna Taylor on the September cover of Vanity Fair was lauded for its artistic value but criticized by some for commodifying the death of the Louisville woman. Many viewers, including Taylor’s family, appreciate seeing Taylor’s name and image in the media six months after she was murdered by officers Jonathan Mattingly, Brett Hankison, and Myles Cosgrove. (At the time of writing, none has been arrested and charged with her death.) But as she grows as a symbol of the movement for Black lives, Breonna Taylor’s actual life story becomes less relevant. And, as many critics have pointed out, memorials to Breonna Taylor do not seem to have a significant effect on bringing about justice.

This type of trauma laundering is not new, but it’s important to distinguish who is sharing contemporary images of Black suffering and to what purpose. In an interview on the history of Black-death-as-spectacle titled “‘What Does It Mean to Be Black and Look at This?’ A Scholar Reflects on the Dana Schutz Controversy,” Christina Sharpe explains that Mamie Till Mobley published photographs of her son’s body in a national magazine to make the violent details of his death real and unobscured. By comparison, Dana Schutz’s painting of Till’s open casket, included in the 2017 Whitney Biennial, solicits a different response. Her relationship to the violence that ended Till’s life is abstract, according to Sharpe, but, as a white artist, Schutz felt entitled to depict it. More recently, Samaria Rice has problematized the use of her son’s image in ways meant to commemorate him. She protested representations of Tamir Rice in a since-canceled show, “The Breath of Empty Space,” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland. Members of the community expressed concern that the museum would not be able to “support the show responsibly” and center the lived experiences of those impacted most by anti-Black state-sanctioned violence. The artist, Shaun Leonardo, has decried censorship, but Samaria Rice has publicly criticized Leonardo for portraying the pain and trauma surrounding Tamir’s death and has requested that he no longer exhibit the images.

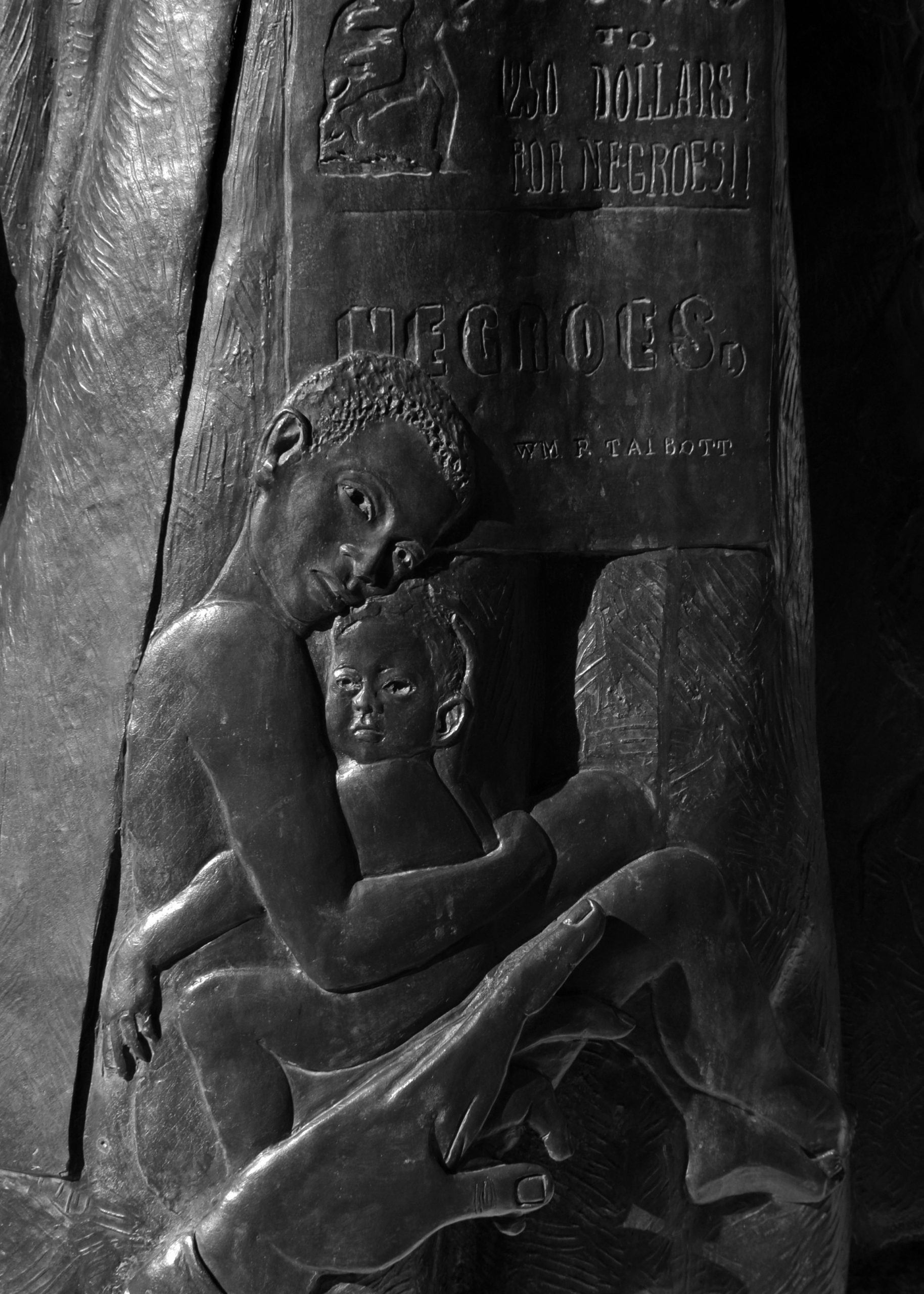

Public monuments rely on a consensus view (however slippery that term might be) of a fixed interpretation of the past. A newly erected bronze by Yonkers-based artist Vinnie Bagwell depicts Truth as she should be seen: powerful. The seven-foot-tall work of public art was installed in Highland, New York, in August 2020 (fig. 4). In Bagwell’s depiction, Truth is older and fully clothed in a simple dress, woolen shawl, cap, and her signature glasses. She holds a cane in her left hand (evoking another common motif of the abolitionist movement, the liberty pole), and extends her right upturned palm (fig. 5 and fig. 6). In the commemorative tradition, allegorical motifs tell a story that is often too complicated to represent in a single form. We see this in representations of emancipation, when a scroll does the heavy lifting to narrativize the fight for freedom in the United States. Likewise, Bagwell relies on easily recognizable symbols to convey pivotal moments in Truth’s life. In the drapery of her skirt are bas-reliefs including a young enslaved mother and child, a poster for a women’s suffrage march, lines from her speeches, words in Dutch and braille, and her name at birth, Isabelle Baumfree (fig. 7).

Despite best intentions, we see time and again how attempts at commemoration can dehumanize the victims at the center of the stories, including historical figures. “Public art reflects the values of a community,” Bagwell explained to me recently in an interview. “And because we’ve been marginalized, Black people want to see ourselves reflected in public art.” Tamika Palmer is grateful her daughter has not disappeared from the larger conversation around police brutality. Cory McLiechey, Sojourner Truth’s sixth-great-grandson, appreciates that his ancestor’s legacy is being fully recognized in the history of movements for social justice. (And similar to the children at the unveiling of the Truth memorial in Esopus, McLiechey felt compelled to reach out to touch the monument and hold his grandmother’s bronze hand.) Artist Grace Lynne Haynes, whose portrait of Truth was featured on the cover of the New Yorker in July, explained in an interview for the magazine that there is a “lack of nuance in portrayals of Black womanhood.” Bagwell echoes that sentiment: “We don’t want to see caricatures or representations,” she told me. “We want to see Black people as people.”

One possible way to move beyond caricatured versions of the past is by paying attention to what has already been done. Art historian Renée Ater has been compiling contemporary interpretations of enslavement and emancipation in an ongoing project, “Contemporary Monuments to the Slave Past,” to understand how modern societies engage with these histories through public space. Ater has laid out a series of questions at the heart of her archive, among them how to define the visual vocabularies that artists utilize in their depictions. This type of repository can serve as an invaluable resource of information as we attempt to reconcile these brutal histories in our public representations of them, and it’s a good place to start. But finding the visual language to articulate the brutality of chattel slavery is only one small part of the larger social project. As Ater explains, documenting the representations of slavery’s past is important because “slavery continues to shape the world we inhabit.” Without first reconciling the failed experiment of Reconstruction and ending the current everyday violence against Black Americans, we cannot memorialize racial equality because it doesn’t yet exist in the present. We march, we protest, we “say her name” because the list of Black Americans murdered with impunity continues to grow.