In 2017 Daniel Benjamin and I organized Communal Presence: New Narrative Writing Today, a gathering of writers and scholars to celebrate and complicate the work of a group of writers that has not often been considered by academic criticism. We sought to build a conference that projected New Narrative in its own image–with panels and readings supplemented by film screenings, a limited edition broadside, poets theater, a risograph-printed program that included space for autographs, a gallery show, and time for mischief and gossiping. This was an academic conference, sure, but still we endeavored to build for New Narrative’s enthusiasts an ephemeral demimonde that might give us new ways to hold on to the writers and books that have mattered to so many of us.

When I finally worked up the nerve to read “Kevin and Dodie,” the final collaboration between Dodie and Kevin that was passed out by ushers at Kevin’s memorial service, I was so relieved to learn that they considered the conference a success. Kevin wrote, “To an astonishing degree, organizers Eric Sneathen and Daniel Benjamin followed our roadmap of who we wanted to share the stage with us” (122), a compliment I wear on my forehead like an invisible star. “Kevin and Dodie” does include one reservation, that we were not able to reserve enough time to name those members of New Narrative who didn’t live to participate in Communal Presence, including Sam D’Allesandro, Bob Flanagan, Lawrence Braithwaite, Steve Abbott, Marsha Campbell, and John Norton. “Ghosts in the smoke,” Kevin calls them (125), bringing to mind the fires that sent down smoke upon Berkeley during the week of the conference. Among the many memories of the conference that linger with me–including Judy Grahn’s heroic reading of “A Woman Is Talking to Death”–is the question of whether or not New Narrative is “queer.” The question came from the audience during a plenary panel organized to celebrate the publication of From Our Hearts to Yours, edited by Rob Halpern and Robin Tremblay-McGaw. I improvised an answer, but I felt my response was insufficient, garbled by the obvious. I was pained, on some level, to try to bring together what seemed like such a natural match: queer literature with queer theory. I had read Ariel Goldberg’s The Estrangement Principle, the most extensive investigation of the relationship between “queer” and New Narrative, in which Goldberg cites New Narrative as an example of “queer” writing that nevertheless “falls through the cracks of gay niche, experimental poetry, and mainstream fiction” (17). And I remembered how Goldberg concedes, “New Narrative, ultimately, was a small group of friends who were making work for each other and not a larger audience that tended to be homophobic or bent on cohesive narrative. Exactly how New Narrative slips through the cracks of literary history is cause for both celebration and alarm” (118). Still, for me, the question revealed how academic inquiry and literary history had failed to make ways for readers to hold on to New Narrative. New Narrative and queer studies, literature and theory, may not be commensurate, but what I did not know in 2017 is that in this case they share a common history.

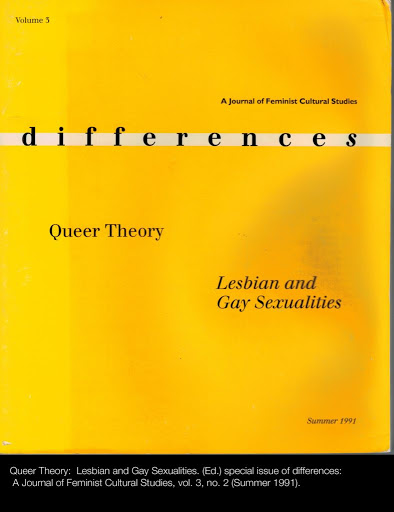

Queer theory and New Narrative scholarship emerged simultaneously at the University of California, Santa Cruz in February of 1990. In the same year that would see the publication of Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s The Epistemology of the Closet, assistant professor Earl Jackson, Jr. presented his paper “Mapping a Gay Male Imaginary,” which climaxed with a close reading of Robert Glück’s first novel Jack the Modernist. In her introduction to the special issue of differences dedicated to that conference’s proceedings, Teresa de Lauretis writes, “The project of the conference was based on the speculative premise that homosexuality is no longer to be seen as marginal with regard to a dominant, stable form of sexuality (heterosexuality) against which it would be defined either by opposition or homology” (iii). Neither their opposite nor their imitation, queer sexualities have their own discourses, cultures, and histories, only partially informed by those of heterosexuality. Further, by using the word queer heuristically, de Lauretis hoped to displace the norms of gay and lesbian studies so that it might better account for racial and gender diversity within the field of sexuality. Compatible with the imperatives of New Narrative, de Lauretis’s vision for “this queer theory” suggests a politics of coalition that is nevertheless rooted in a non-essentialist view of sexuality. Including a contribution by Samuel R. Delany, this special issue of differences collected many essays that were buoyed by analyses of contemporary poetry, in stark contrast with queer studies’ impressively consistent fascination with novels in the decades that have followed. Related to yet distinct from the queer theory stemming from Butler and Sedgwick, de Lauretis’s introduction provides some of the tools academics might have put to use to build yet another queer world—poetry and New Narrative among them.

Beginning with Monique Wittig and ending with Donna Haraway, Jackson’s citations traverse the “gay and lesbian” divide (an important factor for de Lauretis’s early vision for queer theory). Now retitled “Scandalous Subjects,” Jackson’s article from the Queer Theory issue of differences describes the politics informing Glück’s fictions in the idiom of Lacanian psychoanalysis. As a result, Jackson’s claims about the subversive quality of Glück’s prose echo the gendered language of a phallocratic schema, including a femininity associated with being penetrated and a masculinity with penetrating. Jackson suggests that Glück “at once eschews access to the transcendence of the phallus and the unmarked position of absolute truth, through the on-going acknowledgement of the specificity of his body, his desire, and their epistemological consequences” (122). Jackson suggests that just as gay men voluntarily open themselves to the ecstasies of penetration, so too do the narratives of Glück open themselves to a kind of penetration by the world outside of the novel. Jackson brings attention to the embodied quality of Glück’s writing, a positioning that the typical mode of narration often attempts to conceal through objectivity and distance, the means by which the universal substantiates itself. Glück’s politics are informed by an analysis of sexuality and gender that undermines the insidious masculine authoritarianism typical of narrative. Jackson would later transform this article into the final chapter of his monograph, Strategies of Deviance—the first academic work on New Narrative and also including the most comprehensive analysis of Kevin Killian’s writing to date.

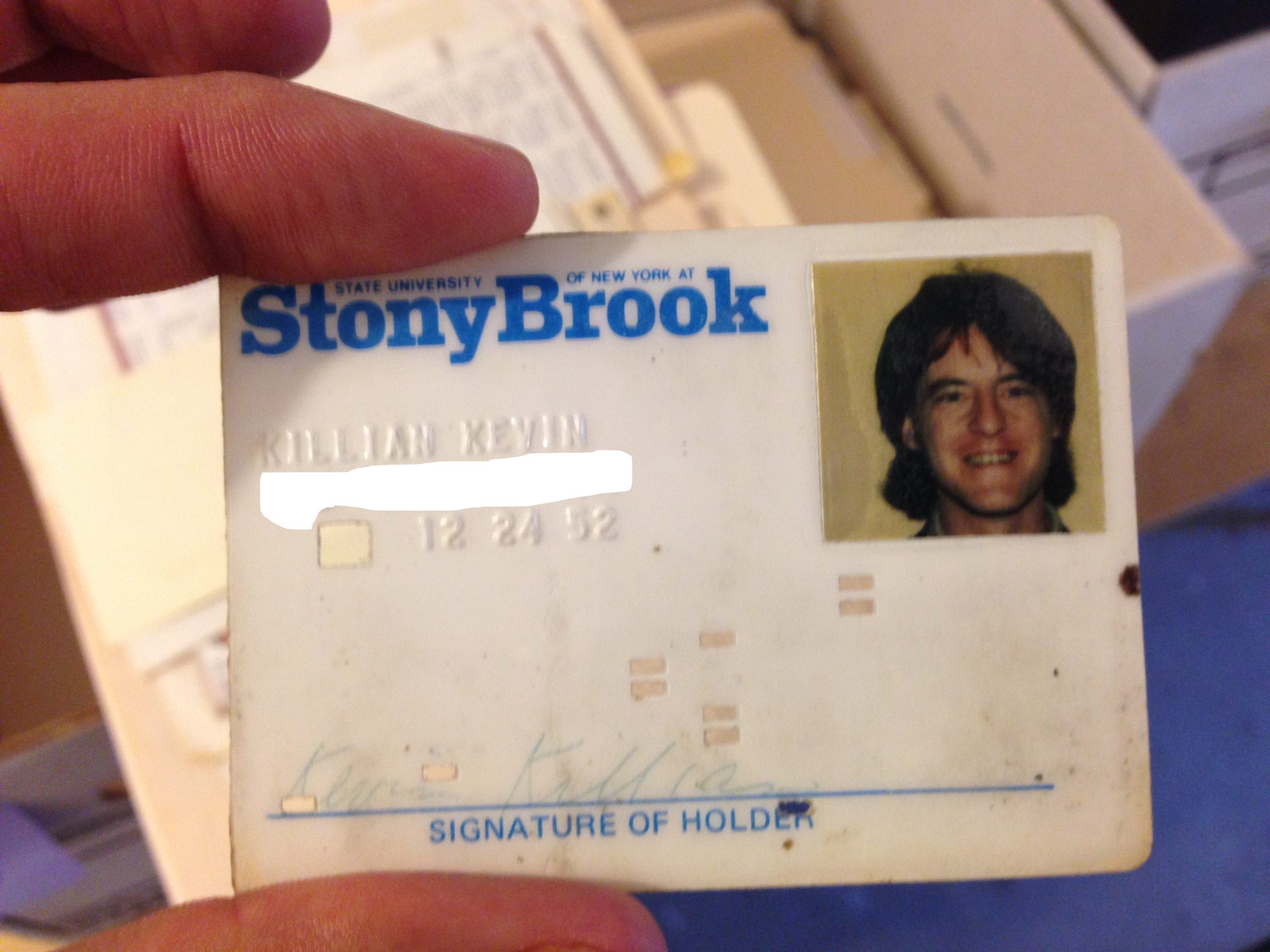

Earl Jackson, Jr.’s relationship to New Narrative began, deviously enough, by way of Latin and a fortuitous read of Men on Men. In his “Sex Writing and New Narrative” Kevin Killian writes, “George Stambolian kindly provided all the contributors to Men on Men with Xerox copies of its reviews. They’re easy to paraphrase, I can do it in two sentences. Edmund White and Felice Picano, as usual, provide us with the finest stories of their careers. As for the California ‘New Narrative writers, all we can say is, ‘Huh?’” (292-293). This response may have been true for most readers, but Jackson remembers his personal response to Glück’s “Sex Story” in glowing terms: “By page two I was absolutely riveted. This was several levels above anything I had read yet in terms of experimentation, voice, and sheer audacity with smarts. The contributors’ notes mentioned that Glück still lived in the San Francisco of story. Would I ever get to meet him? Nah. That kind of thing doesn’t happen.” This unlikeliness may have held from the distance of the University of Minnesota, where Jackson was currently finishing his graduate work, but only months later Jackson was teaching at UCSC. It was a neighbor of Jackson’s, Pascale Gaitet (a professor of French literature at UCSC who, coincidentally, was also the partner of poet Nathaniel Mackey), who would fatefully connect Jackson to Glück. It turned out that she, Jackson, and Glück’s current boyfriend were all in the same Latin class in the 1980s. Such serendipity soon enough landed Jackson an invitation to Glück’s house for dinner. Jackson remembers it fondly, “And that was the first time I sat at that dense, comforting wooden table in that warm and comforting kitchen on Clipper Street.”

As an important member of the extended New Narrative crowd of the 1990s, Jackson certainly would have had his share of gossip to peddle in Strategies, and yet his criticism eschews spilling the tea in favor of psychoanalytic theory, narratology, and textual analysis. Jackson threads through the writings of Dennis Cooper, Glück, and Killian so that Cooper’s influence on Glück, and Glück’s subsequent tutelage of Killian, become present formally, rather than merely anecdotally. One example of transmission with a difference that Jackson considers is the three authors’ different uses of appropriation, building in complexity from Glück’s citation of gay pulp novels like Billy Farout’s Fresh From the Farm to Killian’s appropriation of popular culture that nevertheless “empowers the images in the films and the magazines to express the real emotion and compassion in a culturally legible idiom” (245). The difference, Jackson illustrates, is that Glück’s citation remains committed to the community and discourse of a gay subculture, while Killian traffics in high-stakes camp, making marvels out of the detritus of the mainstream. Given that Jackson spends so much time on Killian’s work, showcasing him as an important multi-genre author and building connective tissue that stretches from the trio New Narrative writers to the deviant strategies of Samuel Delany, Pedro Almodóvar, and back, further, to Oscar Wilde and Leonardo da Vinci (via Sigmund Freud), I can only wonder what New Narrative criticism would be like today had Strategies been received more exuberantly.

Most scholars probably struggle under the weight of such counterfactuals, and it’s hard to know why, in this particular case, Jackson’s scholarship wasn’t embraced. Perhaps it was Lacan, perhaps it was Jackson’s sophisticated prose and his quicksilver allusions, or all the porn, or the devastations of the AIDS epidemic, or New Narrative, again, in the role of the bad object. Perhaps it was Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick? Jackson vividly remembers a private meeting with her following a queer theory conference in 1992, a meeting that Jackson believes soured the possibilities that Strategies might be published by Duke University Press or reviewed in any of the relevant academic journals. Despite this set back, New Narrative over the years has been taken up by a handful of scholars, including Dianne Chisholm, Carolyn Dinshaw, Anthony Easthope, Alan Gilbert, and Kaye Mitchell, and a band of graduates from UC Santa Cruz, including Christopher Breu, Rob Halpern, and Robin Tremblay-McGaw. In their introduction, Halpern and Tremblay-McGaw write, “In a utopian gesture consonant with the clarion call for enhanced community life that marks New Narrative’s inception, our hope is that From Our Hearts to Yours: New Narrative as Contemporary Practice will spur as-of-yet unheard unimagined conversations and texts, new readers and writers, unanticipated solidarities and camaraderie” (14).

Today scholars can return, with celebration and alarm, to de Lauretis, Jackson, and New Narrative to cruise the archives of utopia, an ideal made famous by José Esteban Muñoz. Almost twenty years before the publication of Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia, the subject of utopia punctuated de Lauretis’s introduction to the special issue of differences:

Each in its own way, the essays recast the terms of the discourses they engage to expand or shift their semantic horizons and to rethink the sexual in new ways, elsewhere and other-wise. This elsewhere is not a utopia, an otherworldly or future place and time. It is already here, in the essays’ work to deconstruct the silences of history and of our own discursive constructions, in the differently erotic mappings of the body, and in the imaging and enacting of new forms of community by the other-wise desiring subjects of this queer theory. (xvi)

De Lauretis stresses that utopia is not else-where but already extant by way of the “the essays’ work.” Some might read in de Lauretis’s emphasis an anti-futurity akin to that of Lee Edelman’s No Future. But what if “this queer theory” has also fallen through the cracks? The dreams of “this queer theory,” like New Narrative, still stir up feelings of discontent with the status quo—and not only with what queer theory has become or what literary history has obscured. And, again like New Narrative, de Lauretis’s queer theory—stressing exchange across epistemological divides, committed to a critique of “white gay historiography,” and abundant with poetry—might have thrown down something scholars have yet to really pick up. For Muñoz (and Goldberg), that the horizon of queerness remains “a horizon imbued potentiality,” should not be read as a loss, but be valued for its oneiric, antagonistic effects: “Queerness is a longing that propels us onward, beyond romances of the negative and toiling in the present. Queerness is that thing that lets us feel that this world is not enough, that indeed something is missing” (1).

A year after Kevin Killian’s death, something is certainly missing. His absence reminds us that, yes, this world is not enough; it is his legacy and our memories of him that now propel many of us precisely in the manner that Muñoz describes, onward and beyond. And though it felt sudden, looking back, he did warn us that he would disappear. Killian laid out the whole act in his essay “Poison”:

I’m standing on a flat plain, and then, or so it seems, a little hole appears in the sand ahead of me (like in that movie Tremors?). The hole grows larger in diameter—this is my sanity, and all the little pieces of me of my sanity are breaking up and slipping down into the hole… (92)

[All] the things I brought with me to this valley are in my trailer, fifteen yards behind. And one by one I lose them down the ever-expanding hole—cans, jars, movie magazines, photos, food and books. The hole keeps caving in on itself. My little home on wheels is silver, rounded like the new Volkswagon models, and drives like a dream. Its doors shear off with a sudden crunch of metal, bright in the noon air, they slither across the desert floor into the hole. I’m next perhaps—hold on to me. (101)

Killian gave us so many ways to hold on to him, including the laughter he shares with us over Tremors, that tacky film about gigantic earthworms wreaking havoc in Perfection, Nevada. Killian loves a disappearing act, and, as Jackson pointed out in Strategies with respect to Killian’s use of a Judy Bolton mystery novel in his first novel Shy, Killian installs pop culture in the exhausted heart of his fictions, allowing us to recover experience with both sentiment and wonder. Likewise, in his final novel, Spreadeagle, Killian disappears behind the narrator Kit, who talks on the phone with a sick, house-bound Sam D’Allesandro about the emotionally overwrought film Beaches. Kit tries to remember when they went to the Alhambra Theater to see it, and Sam says, “When we were together… It couldn’t have been that long ago, could it? I don’t remember me and you seeing that movie, Kit. But it was all about how, when a person dies, part of them still lives on as long as the other one has wings to live and fly away” (92).

Killian also communicates with Sam D’Allesandro in “Sex Writing and the New Narrative,” which alternates between Killian’s essay and D’Allesandro’s story “Nothing Ever Just Disappears.” At the first Out/Write conference, Killian read his essay from the front of the auditorium, and Bruce Boone, their mutual friend and teacher, read D’Allesandro’s portion from the back. The notes for this performance and D’Allesandro’s lasting impression on Killian constitute the entirety of the notes on Killian’s “Sex Writing,” which are included in the appendix of Writers Who Love Too Much. Again, Killian disappears into gestures of remembering, refocusing our attention to include the many who might have otherwise fallen outside of the spotlight. In their poem “I Hope I’m Loud When I’m Dead,” CA Conrad writes,

Queer theory and literary scholarship, too, can be used, can be made rich with gestures of great generosity that allow us to hold on to what is dear and vital as we continue to reach for utopia. As queer theory and New Narrative are pronounced from opposite ends of the same auditorium, they allow us to hold on to what might otherwise slip through the cracks, those voices calling out, “hold on to me.”