The hallmarks of poet and novelist Kevin Killian’s style are various—variousness, in fact, may be counted among them. Writer Dodie Bellamy, who married Killian in 1985, speaks of his “protean slips between high and low culture,” modeling an absolute equality of sources and means, and Killian thrills to this combined effect, constructible and cute. But to speak of the illicit kicks of this approach, which implies evaluation, impels a question as to just whose culture one assigns the upper hand, if only for satiric traction.

Killian’s writing savors the contingencies of gay identity—from celebrity obsession, conscripting alternative icons from Hollywood and beyond, to the criminal sympathies of Pasolini or Genet—effectively splitting the difference between violent pulp and a theory-savvy gossip rag. Throughout his 2012 novel Spreadeagle, the time of which spans decades of death and uncertainty under the sign of AIDS, Killian’s trademark unevenness of style seems to derive from the mixed company that it depicts, as though its characters inhabit different genres themselves. More than innocuously discursive, the high-low antinomy that Killian wields as a mechanism of semantic slapstick issues real comparisons between enfranchised and peripheral subject positions, plumbing the vast stratifications of queer life within the framework of capitalism. Refusing dialogic realism in favor of hyper-referential pop cultural pastiche, Killian’s writing spans argots with little regard for finessed consistency.

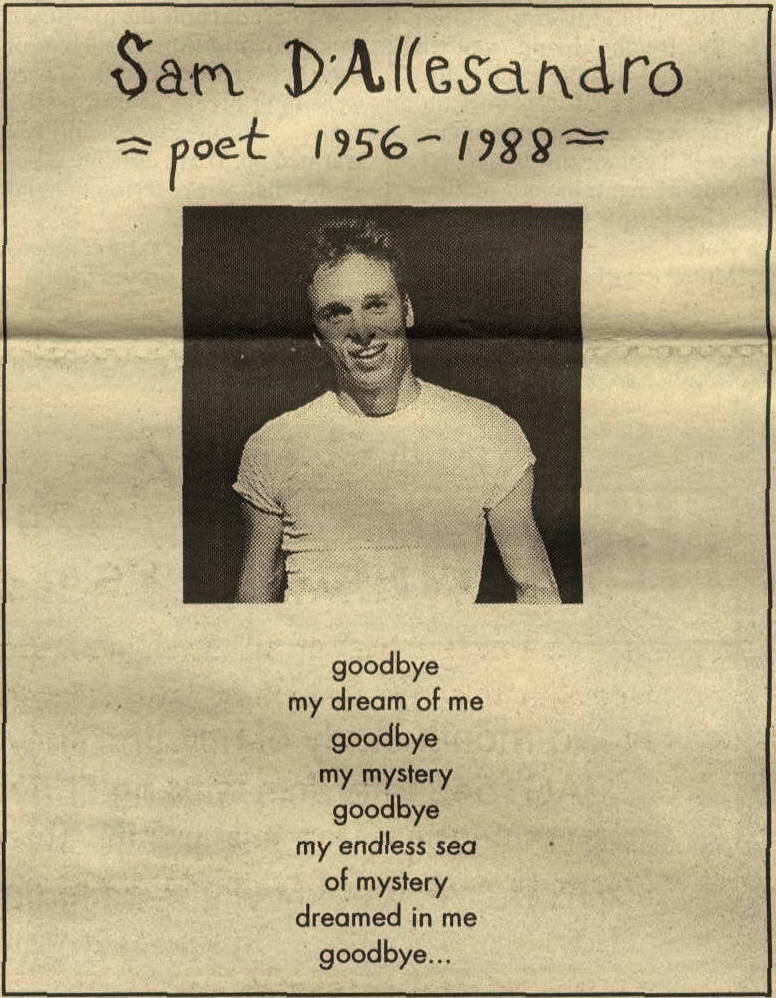

At its core, Spreadeagle fictionalizes the death of experimental writer Sam D’Allesandro, a friend and muse of Killian, whose words are woven into Dodie Bellamy’s 1998 epistolary novel The Letters of Mina Harker. D’Allesandro died from complications of AIDS in 1988, at age 31, though the action of Spreadeagle projects an alternative timeline, extending his life into the twenty-first century. This single death, however, is narrated over the course of a digressive literary thriller, whose separate plots depict the indifferent opulence of bourgeois society and the opportunistic racketeering of a criminal underclass respectively. Initially, the novel gathers around the popular gay novelist Danny Isham and his coterie, who drift in and out of D’Allesandro’s life with philanthropic unconcern. The second half transpires in the company of D’Allesandro’s likely killers—peddlers of a sham cure for AIDS—and rapidly descends from gay pulp into sordid noir. Killian’s preferred unit of plot is the imbroglio, the more embarrassing the better, and he delights in placing his characters in dire straits, such that any hint of elegy sits in uneasy tension with the novel’s sadistic design.

Below the Pleasure Principle

This Sadean pleasure-seeking poses a political limitation, initially. But the salacious fatalism of this approach isn’t Killian’s prerogative alone, insofar as it refracts the values of the neoliberal interregnum in which Spreadeagle takes place. This period encompasses the aftermath of the collapse of the USSR at the so-called End of History as well as the AIDS crisis, which likewise escalated to a genocidal scale during a period of unprecedented government deregulation. (One need only examine the present epidemic of HIV infection in former Soviet Bloc countries to grasp the urgency of this co-theory, linking massive programs of liberalization to contemptuous extremes of state neglect.)

As New Narrative, the loose school of experimental writing from which Killian is inseparable, formed against the backdrop of escalating crisis, one might suggest that its insistence on the pleasure of the text assumes twofold importance, where writing is both a reflection of social reality and a refuge from its difficulties. Initially, the New Narrative writers call attention to the collective contexts of individual pleasure-seeking, documenting their queer community as so many mutually implicated texts. After the appearance of AIDS, however, this program of utopian intertextuality appears to retreat from its source world, becoming increasingly fantastical, interior, and referential. In a devastating afterword to the second printing of his 1985 novel Jack the Modernist, Robert Glück laments that AIDS has since conferred anachronism on its settings and society—the author himself stopped visiting the baths shortly after its publication. Killian observes as much in a 2012 plenary on poetry and AIDS:

In the seventies gay poetry had been dominated by the liberation of the body, but the excesses of the body were banished as though by fiat when AIDS came to haunt us…for much of gay poetry, the body was blamed for the plague; the rectum had shown itself a grave; it was a time when the spirit returned, or when language took on the materiality that had once been the body’s province.

This remark is striking; for the movement whereby language assumes bodily salience also conveys the body to a symbolic order that considerably precedes any single point of view. Language doesn’t flatly represent or quote from reality, but registers subjective discrepancies in its many provenances. More so than most queer prose stylists, even among his peers, Killian embraces the embarrassing dissonance of sentences placed at cross purposes. This enriches another trademark of his writing, namely, the micro-historical texture that results from a compulsive litanizing of proper nouns and pop cultural reference points.

This comparative tack is doubled at the level of plot. The first section of Spreadeagle, “Extreme Remedies,” reads as a comedy of manners, while the second half, “Silver Springs,” descends into the seedier terrain associated with certain of Killian’s direct peers, such as Dennis Cooper. But where Cooper’s novels seem strategically evacuated of historical concern, transpiring in a utopic space of de facto gayness where violence is largely inconsequential, Killian’s omnivorous referentiality situates its characters in historical concert, incessantly name-checking the mass cultural touchstones that mediate each particular vantage. As a result, the sexual and political nihilism of Spreadeagle appears qualified, as an outsourced product of liberal malaise, rather than endemic to an undifferentiated social whole.

Killian’s fiction presents scenes of ultra-violent ribaldry with buoyant humor, and yet refuses the ameliorative designs of straightforward satire, as well as the easy catharsis of so-called transgressive literature. As a Great Recession-era work of counterfactual historical fiction, Spreadeagle appears less concerned with puritan boundaries of good taste than with the immiserated underside of respectability politics, where offense is assured because conditions of life are offensive. In this sense, Killian conveys the depoliticization of AIDS to the myriad displacements of financial crisis, all over the course of a single macabre comedy.

Extreme Remedies

In the opening pages of “Extreme Remedies,” AIDS activist and professional layabout Kit Kramer arrives at the home of his boyfriend and patron, successful gay novelist Danny Isham, from a politically motivated trip to the socialist republic of Cuba. Kit has been travelling on Danny’s dime, “seeing how Castro’s treating the AIDS patients,” (12) whereas Danny’s geographical ignorance evinces a distinctly American brand of security-in-stupidity: “it was only this past September that he’d found out Vietnam wasn’t a Caribbean island but somewhere totally different and Asian” (9).

Such language, hamming up racial insensitivity, pervades Killian’s character sketches: always attributed and always uncomfortable, facing down and thematizing the hegemonically white standpoint of the author’s queer personae with unflinchingly feigned innocence. Early on, one learns of Kit and Danny’s attempt to adopt a young Black girl out of the Valencia Gardens housing projects, filling their home with tokens of contemporary Black culture: “I’m glad we’re past all those tiresome identity politics,” Danny says, “and people are starting to realize that yes, two gay white men can give an African-American child both a loving home and a working knowledge of her culture! It gets better, is my message I guess” (46). This punchline, coopting a progressivist slogan of gay rights, caustically sends up the liberal endgame of cultural assimilation in multiple registers.

Poetically mindful of the polysemy that envelops and extends each noun, where pre-personal association makes chutes and ladders of all language, Killian links San Francisco’s Castro District, a gay enclave named for Mexican military commander José Castro, to the revolutionary socialist state of Cuba, popularly condemned by American ideologists for its putatively anti-gay legislation. (For more on this topic, see Leslie Feinberg’s Rainbow Solidarity in Defense of Cuba.) Nonetheless, Kramer appears to speak facetiously when he extols Fidel Castro’s government: “To honor his recognition of homosexual freedom, we named our primo gay district after this still living fighter!” (12).

This overture, glossing AIDS and US imperialism in a flash, takes place in the secure company of Danny Isham, America’s second-most successful chronicler of gay San Francisco, after Vietnam veteran and novelist Armistead Maupin, whose Tales of the City double as homonationalist paeans to an ever-more inclusive society. Isham has a particularly anxious relationship to Maupin—in a running gag, he is frequently mistaken for the older author, as an unrelated purveyor of apolitical “gay kitsch.” The estranged son of infamously appetitive poet Ralph Isham, known for his activism, Danny’s fanatical disdain for the comparison evinces more than a little Oedipal compunction—while his writing lacks a politics, it is apparently more serious than that of his more famous counterpart. Such are the subtle differences upon which bourgeois self-opinion depends.

The Celebrity Novel

This blending of real-life personages with the antics of fictional peers is a key device whereby Killian advances his comedic critique of society. If the political vocation of the historical novel concerns its interweaving of small lives with those of major historical actors, Killian’s celebrity fixations have a greater-than-satirical significance, as mass cultural linchpins of popular consciousness. In Marxist critic György Lukács’ description of the historical novel, the appearance of famous figures at a distance indexes the gulf between societal strata, initiating a literature from below. Killian’s incessant namedropping offers a mediatized version of this inverted agency, from the standpoint of the quintessential observer—namely the fan, who is never far from being a fanatic.

This libelous insouciance extends throughout the entire book. In the concluding section, “Silver Springs,” the hero, Geoff Crane, makes a living forging celebrity autographs from a trailer park in the fictional town of Gavit—a depressed town ravaged by the spread of methamphetamines, an afternoon’s drive from the wealth of Silicon Valley. Geoff’s racket, as a celebrity impersonator working at the level of the individual letter, traverses the tremendous socio-economic gulf that intervenes between the stars of Hollywood and their earthbound admirers. Nearby, Danny Isham, “the surviving child of a rich man,” cavorts with a real-life literati, whose names litter the page as though the massively distributed punchline of an inside joke—Michael Chabon, Lemony Snicket, and countless more inscrutably situating cameos that lend body and reputation to Isham’s society (82).

Isham’s own success stems from a series of novels documenting the lives of Rick, “the rich, light-hearted playboy of the Castro” and his partner Dick, “the poor, ethnically-mixed street hustler with an attitude, but a heart of gold” (129). This storybook complementarity seems a cheaply allegorical emanation of the uneven social planes on which AIDS is experienced, and an obvious commentary on the many strained and complicated pairings that comprise the novel’s cast. Kit and Danny’s own relationship is less symmetrical, though a modicum of jealousy is required to smooth over the fact of financial dependency. For want of a nuisance, their relationship is triangulated by a live-in fanboy, Eric Avery, who at the same time insinuates himself into the company of Kit’s ex-boyfriend, the writer Sam D’Allesandro, dying of AIDS in his cramped apartment.

Zones

From his first appearance, D’Allesandro is in desperate straits and declining health. After his breakup with Kit, “Sam had retreated to this cheerless, empty interzone, where all you saw were people smoking crack or hauling giant slabs of debris into artists’ live-work lofts to make public art for the walls of the Yerba Buena Center downtown” (142). The Yerba Buena Center, a stone’s throw from San Francisco’s so-called skid row, is a representative icon of development atop, or nearby, dereliction, and was once the focus of a bitter legal struggle between low-income tenant organizers and the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency. The interzone of which Killian speaks, where D’Allesandro whiles away his final hours, is a space of combined and uneven despair, where AIDS death and the transient residency of those struggling with addiction and unemployment factor into the machinations of private developers.

Again Killian juxtaposes a specific inventory of the city with his own embellishment, as a fictional overlay to the actual, historical world in all its brutality. At least one of Spreadeagle’s core characters derives from this bizarro-realist program, too—as noted, D’Allesandro was a friend of Killian’s before his untimely death and remains an underrated writer to this day. Killian’s decision to resurrect his muse on the page offers nothing like simplistic wish fulfilment; for the fictitious D’Allesandro appears ailing, piteous, even after having outlived his historical counterpart by decades. In this guise, D’Allesandro assumes looming significance, for his death and the question of its attribution drive this novel and divide its two halves.

In the first half of the novel, a sickly D’Allesandro is visited by a manipulative salesman, Gary Radley, who offers him an experimental therapy called Kona Spray, at cost of his entire savings. Radley’s business, Extreme Remedies, corresponds to any number of unscrupulous ventures whose profits are parasitic of precarity. The marketing language of Extreme Remedies indexes fantastic distance, too, peddling a primitivist idyll wherein a neo-colonial consumer may infuse their personal space with Edenic innocence: “People in Hawaii don’t get HIV, the copy says, because they bask all day and night, all year round, in the healing blossoms of the Kona plant. Now you can bring the healing power of Kona to your own bedroom or office” (391).

Naturally, the therapy performs no miracle, and when Avery discovers D’Allesandro dead in his apartment, he panics and retreats from the scene, nabbing a laptop as a memento (256). This is the final wedge between Kit, Danny, and their listless houseguest. “You mean he’s dead and you just let him lie there?” Kit spits incredulously at Eric upon hearing the news (254). The question of not only guilt but culpability rears up as Danny’s bitterness impedes Kit’s grief: “He was dying for years and you just let him die there,” Danny accuses, jealous of a corpse (ibid).

Silver Springs

D’Allesandro’s diagnosis may have coincided with his breakup with Kit Kramer, but the time of his sickness corresponds to a descent in both strata and scenery. The correlation between illness and downward mobility is well-observed, but these vectors of harm appear throughout Spreadeagle as two mutual metaphors, each representing the other, as the action drifts from San Francisco in an era of cultural resignation after the height of AIDS to small-town California as one site of an incipient methamphetamine crisis.

Both epidemics and their ravages concern the sociality immanent to the individual body, and Killian graphically describes the physical ravages of addiction as a sexual affliction, too. Identifying drug use from weight loss and skin sores, Geoff Crane’s doctor appeals to his vanity: “soon you’ll have those crystal bumps up and down your penis, Geoff, and how are you going to explain those away?” (485) Here formication is a social symptom, linked at its basis to both folkloric and somatic manifestations of AIDS.

In “Silver Springs,” portions of which were anthologized as early as 1991, Crane, a hapless counterfeiter living with addiction in the trailer park of Gavit, enters the orbit of the evasive and homicidal Gary Radley, whose appearance in the economically downturned town alludes to darker purposes than Geoff’s seduction. The mystery deepens when Eric Avery, now a semi-famous porn star known for his ability to take a spanking, materializes in town at behest of an elderly discipline enthusiast. When Avery reveals to Crane that he has footage of Sam D’Allesandro’s murder, Radley promptly executes the only witness to the crime, implicating Geoff in his death. Guilt-addled and pushed further into debt by drug-fueled escapism, selling his possessions and eventually his trailer, Crane’s capture soon appears the inevitable culmination of his affair with Gary Radley, a Sadean mafia unto himself.

“Silver Springs” is a horror novel compared to the rollicking satire of “Extreme Remedies,” but it proceeds by the same formal means, relying upon Killian’s signature collisions to disclose the brutality that small-town life barely conceals. If anything, the subjective violence of this latter section is obverse to the cruelty that bourgeois society outsources and represses. Sam D’Allesandro dies in secret, his apartment a correspondent shambles, while Gary Radley’s trailer is a sordidly revolving door of mortal prey, rendered in malodorously Huysmanian detail.

In allegorical fashion, the novel proliferates awkward and adversarial dualisms. The sinister twins Gary and Adam Radley, recurring characters from the conspiratorial subplot of “Extreme Remedies,” face off against the criminally implicated Geoff Crane and his brother Jim, a small-town policeman: “Jim’s a county cop and kind of a hick, wears a big .45 on his hip like so many guys in our town, only he gets paid for it” (371). Jim represents the lawful obverse of a lumpen company, policing the people that the Radleys exploit—including his own kin. Questions of relation and resemblance follow a richly incestuous trading of places from scene to scene, mixing the mutable moral typologies of George Bataille’s L’Abbe C with the fraternal archetypes of Bruce Springsteen’s “Highway Patrolman.” As Crane’s own sympathies are torn between erotic fascination and fraternal obligation, he pivots between societies, though his company is ultimately determined by the escalating physical possession of drug addiction.

However chaotic it appears on the surface, the symmetrical design of Spreadeagle is a higher-order emanation of Killian’s manic paragraph, a multi-registral juggling act where the left hand always knows what the right hand is doing. Toggling between genres, Killian relies upon the reader’s conversancy in Hollywood lore for a sentimental charge, as well. Spending time with his prose is like bonding with a stranger over a common fixation, and his characters are never so relatable as when they are themselves obsessed. Geoff Crane, for example, summons the innocence of Audrey Hepburn’s character in Wait Until Dark as he descends into criminal life, turning a blind eye to his own misdeeds. Through this identification, he can redeem and glamorize his lack of agency, as even fatedness requires another’s example.

A Dream of History

More than a fantasy by which to deal with the untimely death of a friend, resurrecting a specific casualty of AIDS in order to kill him less senselessly and concentrate the blame, Killian’s roman noir implicates myriad subjective and objective forces, from true love to real estate, in the making of a single death. The fictionalized D’Allesandro remains as fated on the page as in reality—even in sickness one dies too soon. But over the course of this slapstick thriller, Killian socializes the only apparently private stakes of a people’s illness, such that one man’s tragic mishandling by friends and conspirators becomes an allegory of liberal neglect. Rewriting tragedy as farce, and comedy as crime, Killian forces closure, and Spreadeagle ends in an improbable jubilee. The ending, he has said, appeared to him after years of waiting, in a dream.

This morsel of trivia reframes the book, reminding its reader that the effortlessness with which Killian appears to write nonetheless crests atop historical and subjective necessity. In a 2019 interview with Ruby Brunton, Killian explains that it took him twenty-three years to complete Spreadeagle, the conclusion of which finally arrived as though a godly visitation, something out of a historical machine. Traces appear in Killian’s earlier story collections, such as I Cry Like a Baby and Little Men, and in numerous publications starting as soon as 1991. But what caused this delay, such that Spreadeagle may be described as both its author’s first novel, and his last? As Killian explains, “the nineties were spent largely in hoping for a cure for AIDS. We didn’t get a cure, exactly, but we got enough.”

While the writing of Spreadeagle’s good-enough ending seems to have awaited the uneven abatement of AIDS, its narrative design demonstrates against foreclosure. Narrating a dual exploitation of the gullible ill and the pliable poor, Killian’s macabre plotting insists that one cannot speak of an end to the AIDS crisis, in spite of its increased management within affluent and largely white enclaves of the imperial core, where the economic vectors of infection persist.

Much as HIV and AIDS chiefly afflicted gay men during a period of cultural persecution, it continues to impact marginalized populations today. HIV appears an index of proletarianization, which is precisely why a liberal rhetoric of inclusion can only fail politically: as a highly selective means of crisis management, official strategies of recognition simply outsource privation to the nearest periphery. This process forms the mercenary backdrop to the action of Spreadeagle, which depicts one character’s hellish descent only insofar as narrativization negates objectification. This, to be clear, is the best thing a novel can do for the people whose predicament it borrows, reintroducing movement to the prejudicial portraiture of popular opinion.

Perhaps it makes sense that Spreadeagle took its otherwise prolific author a quarter-century to complete. With respect to its scale and the interpenetrating depth of its comparisons, Spreadeagle is a historical novel of the long present. This isn’t to offer a politically instrumental reading of this labyrinthine text, nor to distort those respects in which it may also be a love letter to a city and a violently departed friend. These layers are inseparable where Killian’s mordant humor exudes a utopian imperative, and his taste-based transvaluations extend the program he outlines above—to liberate the body and the word by way of one another, in a novel or a world. This is just one of the impossible dreams that Kevin Killian imparts, and it resounds throughout all of his work. It’s up to his readership to make it resound everywhere else, in tribute to the slyly subversive optimism that was only one of his charms.