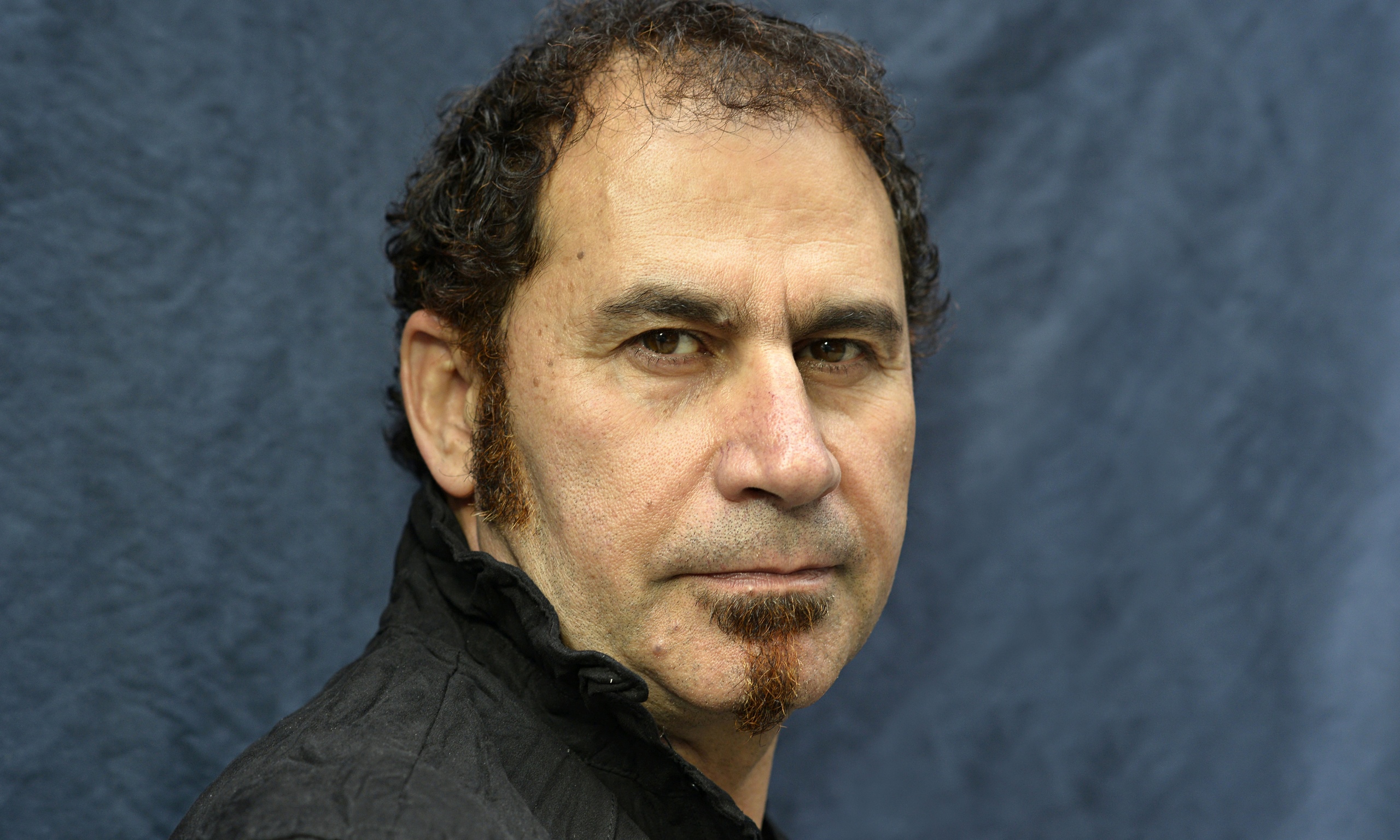

The following is an edited transcript of an e-mail interview between Iraqi fiction writer and essayist Ali Bader and Social Text Online editor Anna McCarthy. Bader’s story “The Corporal” appears in Iraq+100: Stories from a Century after the Invasion, a new anthology from Comma Press.

Anna McCarthy (AM): Sobhan, the title character in your short story “The Corporal,” is a hapless optimist. As a soldier in Saddam’s army, he has witnessed great cruelty and corruption. His body is alloyed with shrapnel and he has lost an ear to the poor aim of an Iranian sniper. Yet he retains a sense of wonder. In a comic ceremony, he buries his ear—a “little cadaver”—on the battlefield. He bears no malice toward the well-trained American sniper who, in 2003, after the “end” of the Iraq war (“mission accomplished”), dispatches him to heaven with a shot to the forehead. “War,” he tells the reader at the beginning of the story, “taught me all about laughter and levity.”

These “wise fool” qualities make Sobhan an appealing character for the reader. What is his appeal for you, as a writer? What work can comic characters do, as narrators?

Ali Bader (AB): The most appealing thing about this character is his absurdity, the method he follows in understanding the world. Sobhan finds this world to be disturbing, because, as you know, the war changed the logic, changed what was commonsense during peaceful times. So we cannot understand the world of the war with the same logic we are used to using; we have to change it. We also have to change our mentalities, our lives, and our habits in order to bear this new world. For Sobhan, he changed the equation: peace/war; the stability in peace becomes instability in wartime; settlement becomes displacement; the act of creation becomes an act of destruction; and, finally, life becomes death. Therefore, we need another language to understand such a world, and Sobhan invented his language—which is an ironic language, a sarcastic and metaphoric one. For him, as well as for me, this is the only way to understand the world of the war.

AM: How did the idea for this story come about? What changed from start to finish?

AB: I think the story came about by mere coincidence, if not by destiny. I was a soldier back in 2003, and I happen to have photos of this time—a lot of them—where I’m with some friends from the city of Kut, eating fish, sporting a mustache and wearing a uniform. These details were my inspiration. So I sat down to write a story, and the writing flew so gracefully that the story was on paper in two days, and then after a week of rereading the story and modifying some of the details, I had its final form. The essence of the story came to me from words, images, and smells that lay deep in the back of my memory.

AM: I like the way the story avoids the seductions of many war narratives. It does not attempt to pull us in with a deep, gripping account of the protagonist’s induction, his combat experience, the aftermath, and so on. Instead, Sobhan rattles off all the signature elements of the war story as one long list: “We were assigned to units, we killed, we attacked, we occupied, we earned medals….” A few sentences later, an almost identical list describes the military career of the sniper who kills him.

A lot of your stories are based on extensive research, including interviews. I want to ask if this way of describing war has any relationship to the storytelling styles of people you’ve spoken to in Iraq, people whose lives have been dominated by war for generations.

AB: What put me on the other side of a line, a little far from my fellow soldiers, was my constant desire to analyze the world that surrounded me. I didn’t fit or belong and I didn’t fully indulge in this world of war, so I had a different experience than most of the people I was with. Still, I was fascinated—not as an admirer—by the soldiers who thought that the war was their lives and that they had to live this life of war as if they were married to it. They seemed united under the word we. To kill, to destroy, to win were not individual acts within the larger context of the army. The fact that they were real soldiers fascinated me, so from my first days as a conscripted soldier, my peers were far apart from me as soldiers and fighters, but close as human beings. I was trying to understand them, to figure out how they had come to cope in this kind of life. My journey in the army allowed me to speak to many of them about their lives and the things that amazed me about them and that I couldn’t comprehend. There was a gap I was trying to fill during that time—and I think my novels and stories fill that gap using the other soldiers’ stories.

AM: The story is full of animals. Much of it is Sobhan’s way of talking–he repeatedly describes the moment of his death by alluding to bits of brain flying out in the wind “like bird droppings.” He also speaks of sheep, a lamb, dead cats, a dead buffalo, a camel, and a pig. At one point he describes troop morale by comparing it to “a dog whose owner has just died.” Then, at the end of the story, the Iraqi president a hundred years in the future is seen on television with his dog. Can you say something about how you see animals in this story? Why does the president have a pet?

AB: As soldiers on the frontier, one of the few things that remained consistent for us was the presence of animals. The war diminished and buried urban life. We didn’t see buildings, paved streets, shops, or women; the only things we were able to see out there were animals—birds, rats, dogs, sheep, insects. In the story, then, Sobhan turns to his true self, to the basic surroundings and what’s familiar to him.

Coming to the second part of your question: I attribute the appearance of the Iraqi president with his pet on TV a hundred years from now to the incident where George W. Bush appeared on TV two days before the invasion with his dog Barney and threatened Saddam. You could say I wrote the scene out of a presidential inspiration.

AM: The story is very cinematic, but it’s not as if it limits its visual style to only one film genre. When Sobhan ascends to heaven surrounded by garbage, dirt, and drying underpants, I’m reminded of a movie like The Matrix, with its hyperrealist special effects. Then, later, when an angel is holding Sobhan by the collar and he kicks as if “swimming in space,” cartoons come to mind. Do you think in images? Do you see the story in filmic glimpses as you write?

AB: As a writer, it’s much more complicated, since writing—for me—consists of two stages or levels. The first one is verbal, where feelings, concepts, ideas, and events play the major part in the process of analyzing and interpreting what’s been written, while the visual—which is the second stage—contributes in an immense sort of way to saving us from the weight of the language and can place us in a world of images and movement. And that of course has its effect on the reader’s mind. In my story, I used the visual effect from the very beginning to stimulate and move the reader’s mind along with the action and to allow the reader to interact with two worlds, the world of the war and the world of the afterlife or what’s beyond death. And since the world of the war is actual, real, and known, it has a lot of concrete images that we can relate to. The world after death is the opposite, still mysterious and unknown. Jumping back to your earlier mention of irony: I felt that a cartoon-ish type of event was more to the point.

AM: I wouldn’t call this story science fiction–the presence of God and the angel and Socrates tells us that we are not in a technological universe, but rather in an idiosyncratic, quasi-allegorical story world. Still, certain aspects of the story achieve a sense of estrangement comparable to the effects brought about by other time travel stories. H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine, for example. I’m thinking particularly of two moments: the first is Sobhan’s first conversation with a stranger in the future. There’s a great exchange in which we learn that Sobhan’s twenty-first century style of speaking makes him sound angry. Then, soon afterwards, the stranger tells Sobhan about an “artsy coffee shop” where “it’s all free if you don’t have money on you.” I like this image of utopia. It’s not a world where money has been abolished; it’s even more radical–it’s a world in which money has so little importance that you can forget to carry it and still consume goods and services. Another way of saying this is that it’s a world where there is no systematic means for extracting and circulating value. You say you’re not a science fiction writer, but surely you enjoyed crafting these moments. I feel as if this is where the story is very clever in letting things hang between irony and sincerity.

AB: Crossing into the future is a very old dream and a fascinating one. And many writers have taken it up, especially when we consider a futuristic, avant-garde type of literature. And yes, I though about Wells and the time machine, but I took his idea and ran with it in the opposite direction, because—as you know—he was extremely pessimistic due to the political and social conditions in Europe and around the world at that time. Therefore, his idea of the future was very tragic, and he represented his belief that capitalism would bring the entire human race to the ground.

I was half-pessimistic in my representation of the future. I painted a futuristic picture of Iraq and an estimation that a country and a society will change for the better even as they keep on falling under terrorism…this image is the opposite of what the West presented. Yes, the country will fall under terrorism, but it will rise from within.

So as to the genre of my story: I can say that regardless of the sci-fi elements my story has adopted, it still falls under the genre of fantasy. It’s art about possibility.

AM: A number of your works have been translated. How have you come to think about the process of working with a translator? To what extent does the procedure feel like, say, an extension of the writing process? Has the translation ever changed your thinking about a particular piece of work? Do you ever think about translation as you write?

AB: Translation stands on a high level in the writing process. Without it, life and literature would be put in small boxes and limited only to those who read in many languages. It’s also important to the writer, because it breathes new life into the book and its author. Translation facilitates communication among societies, cultures, and individuals. Of course, I’m glad that some of my books have been translated into different languages and every single translation makes me thrilled. And ultimately I do think about the translation while I’m writing because translation boosts my human dimension. After all, I started as a young writer in Baghdad, basing my thinking and knowledge on locality and things I’d read. But since my words somehow became international, my way of thinking became so as well. And as the circle of my readers expanded, so did my list of heroes. And my topics grew beyond the local and geographical. Translation simply placed me in the midst of the world rather than on its platform. It transformed a writer who thought only of himself and the small circle around him into—what can you say—a citizen of a vast and grand world.

AM: Interviews in British Sunday magazines often ask something like “where do you see yourself in ten years?” I find this question uninteresting. But I am interested in knowing whether your life and career now are what you envisioned them being ten years ago.

AB: In fact, I think a lot of my own future. But I can say that all of my expectations fell through, and my life took a different turn from what I expected ten years ago. In the past, my future was linked to the country I lived in, my family, and to some circumstances out of my power as a human being. Or at least, that’s what I thought. But now things are different for me: as a refugee, I was granted a new life, a new beginning. And now I’m free, and that freedom and that chance gave me and my literature a fresh glimpse into the future. Now things don’t depend on where I live; literature and writing are my identity and my country. So, when it comes to the future I only see writing and I think of myself as a writer, with more opportunities yet to come.