Even with everything in such turmoil since Antoine’s body had been found on the beach, Maï was very happy that Emilie had decided to come see her. The two friends Skyped all the time, but it was the first time they had seen each other in person since Emilie had left Senegal for Europe over a decade ago. It was Maï’s life that was now in crisis, but Emilie couldn’t stop talking about her early days in Europe. “You don’t know what I went through,” she began. Although Maï had already heard the story a hundred times over Skype, she was glad for the distraction from her own troubles. “People think that life is easy there, but it’s like jumping out of the frying pan into the fire. You have to use your own wits, because there’s no one to take pity on you.”

Emilie would always open her exile story with that hustler at Brussels airport, that made Maï laugh at her naivete. When she had arrived in the Brussels airport, a man had approached her, smiling, and had spoken to her in Wolof, as if he knew who she was and had been waiting for her. He kept asking how Pap was, and how was Biram Faye, as if she was supposed to know them. Emilie was too anxious to disappoint the man, and so relieved to hear someone speaking to her in Wolof, so she responded that they were all fine. She should have told him off, but she let him carry her bag and followed him to his car.

Thus, Emilie negotiated the retelling of her story, which Maï now knew by heart as if it was her own. That was how Emilie landed at the Hotel Katanga in the Brussels district called Matongé, at a hostel run by Mama Koko, the first woman general during the war between the Hutus and the Tutsi in eastern Congo. Mama Koko’s motto was, “be feared and respected, or be walked over by all the worthless people in this world.” Yet, she treated all the girls in Hotel Katanga like they were worthless because no one feared them. If they didn’t do what she wanted them to do, she beat them and locked them up in her special room, called “Apocalypse,” for three days without food. The men were afraid of her, too; if they cheated her out of the money they received from the girls, they received even worse treatments. Some ended up dead in an alley with a bullet between their eyes, or deported to their homes in Africa. Emilie’s flight took place during the year of Sopi (change), which brought Abdoulaye Wade to power, and yet changed nothing in the lives of Maï and girls like her.

The majority of the girls at the Hotel Katanga were from Congo and Rwanda, but there were also Nigerians, Ghanaians, and Senegalese. The girls from each country reported to a man of their nationality, who then reported to Mama Koko, the Commander in Chief. It wasn’t good for the girls or the men in charge to disturb Mama Koko, whom everyone feared and respected.

Mama Koko’s influence extended beyond the Hotel Katanga. She had all the police of Brussels in her back pocket. If a girl was in trouble, all she had to do was mention her name, and the police would drive her back to the hotel. Any other girl would be taken to the police station and immediately processed for a quick expulsion from Europe.

Mama Koko had an occupation for every girl in the Hotel Katanga. Most walked the streets from the Midi working-class neighborhoods to the bourgeois enclaves of the Rue des Bouchers to the residential areas around the Tervuren Museum. When girls became too old to walk the streets, Mama Koko sometimes found a toubab to pay a dowry to marry them, or if not, they were employed as hairdressers or restaurant workers in Matongue, or cleaners in hotels around the city.

What attracted every girl to the Hotel Katanga was the dream of finding a toubab husband who could free them from all the troubles they left behind in Africa and all the troubles in front of them in Europe. No girl was authorized to find a husband for herself. Every year, Mama Koko succeeded in marrying off at least ten of her girls to men based in Belgium, Holland, Germany, and as far away as Norway and Finland. And they were good men, too, with stable jobs and good reputations in their communities.

Mama Koko looked all over Europe for men who were tired of feminism and women’s equality, men who were looking for a traditional marriage, just like their fathers and grandfathers before them. Men who wanted to come home from work every day to find their wives and a warm meal waiting for them. Mama Koko could provide these men with submissive, clean, and loving wives who would fear and respect them as the heads of the family.

When Emilie arrived at Hotel Katanga, they put her with three other Senegalese girls in a wing called the French Quarter. The stories the girls told her about life at the hostel were so scary, she could think only of how to survive in this place. So she did everything Mass, the Senegalese overseer, told her to do. She avoided running into Mama Koko at all costs.

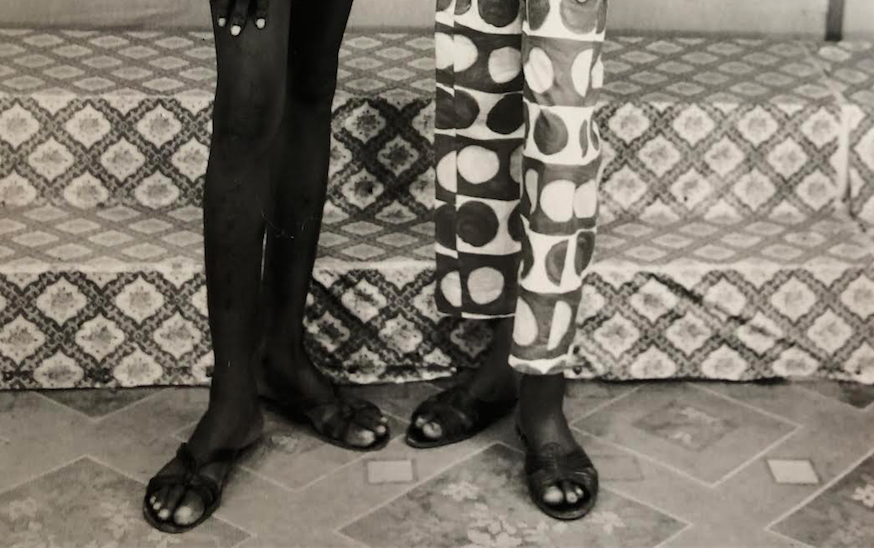

It was freezing cold in Brussels, unlike anything Emilie was used to in Senegal. At first, she felt she was going to die of cold when she was sent out to the street to wait for men to pick her up. But the other girls taught her how to dress sexy and stay warm for a long time in the cold. They also taught her how to avoid danger by recognizing types of men just from the way they looked at her—how to discern the racists and the perverts, the women-haters and the serial killers. Emilie prayed and prayed every evening for Jesus and the Virgin Mary to protect her from bad men.

Then, just six months after she had landed at Hotel Katanga, the Senegalese overseer told her that Mama Koko wished to see her promptly at 8:00 that night. “But, I have to go to work,” she remembered saying, as if that was a good enough excuse to get her out of a sit-down with Mama Koko.

Emilie wondered what she could have done wrong. She prayed and prayed for Jesus and Mary to save her from Mama Koko’s wrath. Then she asked the girls she could trust at the French Quarter what they thought she might have done to displease Mama Koko and what she could say in her defense. Most of the girls said that somebody could have lied about Emilie holding out on Mass and Mama Koko.

“But it’s not true,” Emilie insisted. “I give them all of my money, every evening, when I come home.”

One girl said that maybe Mama Koko was summoning Emilie for a “partooz.”

“What’s that?” Emilie asked, eyes wide open. All the girls laughed.

“You don’t know what a partooz is?” asked the same girl. “You know that Mama Koko is bisexual, right?” The girl looked around to make sure there were only trusted ears in the room. “Well, a partooz is when she has it with a boy and a girl, or more, at the same time. She invites them into her penthouse, has them serve her some of her favorite champagne and hors d’oeuvres, and then she gets in bed with them, some in front and some behind her. If you please her the first time, she’ll keep on inviting you over and over again. Then your overseer will have no power over you. In fact, he’ll fear you and respect you, as if you were Mama Koko herself.”

Emilie was even more scared of being called for a partooz with Mama Koko than being found guilty of an infraction of the house rules. Having a partooz with Mama Koko sounded worse than the sex games that Madior used to ask her and Maï to play with his old toubab friends. How could she pretend to love Mama Koko’s body, which she associated with fear, orders, and punishment?

Back in Senegal, the naked games she and Mai played with old toubabs were different because they didn’t know them. Mama Koko, on the other hand, was a human, someone she knew. Emilie feared her like she would an elderly figure in Sendou, someone she had to respect like her own father and mother. Playing a sex game with someone like that was unthinkable. It was an abomination, for which God would never forgive you. “Do you understand me, Maï?” she asked.

When the time came to see Mama Koko, Emilie prayed and prayed to Jesus and the Virgin Mary to save her. The elevator door opened into Mama Koko’s penthouse, and Emilie was greeted by incense and a loud sound of bass and percussion that made the ceiling vibrate. Mama Koko was dressed in an army uniform. AK-47 rifles hung from corners of the apartment as if they were art pieces. Emilie noticed right away that there were no other girls or boys. So, this was not a partooz. But she had a sudden feeling that her life was in danger. She wished now that there were lots of girls and boys around. Instead, she was alone to face her, with all those guns in every corner, the loud music, and the strong odor that made her heart beat faster.

“Oh, Emilie, it’s you. Come in, come in.” Mama Koko walked toward her, an AK-47 strapped to her shoulder.

Emilie thought she was already dead. “Sweet Jesus, please save me,” she said to herself.

“What did you say? Let me turn down the music.”

“I said, good evening Mama Koko.”

“Oh, I thought I heard something about Baby Jesus. Come in, come in, and have a seat here. You see, I was unwinding before I go to bed. I train for war every evening. That way, I don’t have my recurring nightmares of the border of Congo and Rwanda. My sister and two of my best friends died in that war. Did you know that? I’ll tell you the story one day. Sit down, sit down. Do you want something to drink?”

“No, Mama Koko,” Emilie managed to say.

“Don’t be afraid, relax. I have good news for you.”

Emilie told Maï that she had heard a voice rise and fill Mama Koko’s apartment. Emilie swore that it had not been Mama Koko’s voice she had heard—it was powerful, holy. Emilie explained that the Commander in Chief of the Hotel Katanga had brought her up to the penthouse to sign a contract. They had found her a husband in Germany, she told Maï, in a town called Kassel. He had just divorced his German wife, who he said had emasculated him with all her talk about women’s equality. She was always after him for not contributing to the household chores like washing the dishes, making the bed, cooking, and even changing their daughter’s diapers.

Horst Freud, Emilie’s future husband, had told Mama Koko that he no longer found any pleasure in being with German women, with all their talk about feminism and equality. That was the reason he had come to her: to find himself an African woman who was still fresh and not afraid or ashamed of pleasing her husband.

“Can you imagine these white women losing such good men simply because of dirty dishes and unmade beds?” Mama Koko had said to Emilie, laughing.

That was the first time Emilie had seen Mama Koko laugh since her arrival at Hotel Katanga. In that moment, Emilie was a little less afraid of her. She even looked human–attractive, with bright eyes and a dimple on either side of her cheeks.

The terms of the contract between Emilie and Mama Koko were as follows: Emilie would owe her 15,000 euros after marrying Mr. Freud. He would additionally pay Mama Koko 15,000 euros as dowry. In return, Emilie was assured she would be marrying a good man. Mama Koko told Emilie that she had conducted a thorough background check on him and found that he was in good health, without alcohol or drug problems, and that he had been regularly employed at the VW factory in Kassel for the past twenty years. Mama Koko had also supplied Mr. Freud with a good report on Emilie’s character and physical health, which satisfied him.

That was how Emilie left the Hotel Katanga and the streets of Brussels with Horst, her groom. All the girls were jealous of her for finding a husband in just six months. They said that she was lucky like Cinderella, or that she had brought some powerful medicine from Senegal. But Emilie knew that it was Jesus and the Virgin Mary who had lifted her out of the gutter and the sinful life she had been forced to live since she was fourteen. She was saved.

Just a fortnight before, a man had come to her one night while she was walking the streets near the Tervuren Museum and given her pamphlets about Jehovah’s Witnesses. The man had told her to leave the streets and God would change her life forever. He had given her a business card and some pamphlets. He had said something big was going to happen to her soon, before he disappeared in the dark. Emilie told Maï that the day after her visit to Mama Koko’s penthouse, she had gone straight to the address the man had given her. “That day, I changed my religion from Catholic to Jehovah’s Witness, the true path to God.”