David Wojnarowicz and the Politics of Representation

Discussed: “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture,” National Portrait Gallery, Washington DC. October 30, 2000 through February 13, 2011.

David Wojnarowicz often said that he wanted his art to be an “X-Ray of civilization.” Eighteen years after his death, at the age of 37, from AIDS-related complications, his work has apparently lost none of its radioactive power. When Martin E. Sullivan, the director of the National Portrait Gallery, caved to demands from the Catholic League and several prominent Republican congressmen — including soon-to-be House Speaker John Boehner — to remove a video piece by Wojnarowicz from public exhibition, it was as if he had inadvertently exploded a time-bomb loaded with the shocking affective charge of a bygone era of queer expression. An event that, for many, felt like an acid flashback to the bad old days of the 1990s Culture Wars has actually revealed a much more far-reaching — and disturbing — discursive constellation of political agendas. What might have been dismissed as a wearingly familiar debate about censorship and government funding of the arts has turned out to reveal a lot about the still-uneasy status of queer representation in the national political imaginary.

The offending video, a four-minute excerpt of a thirty-minute work called “A Fire in My Belly,” was displayed as a part of a temporary exhibition on the theme of American portraiture and sexual difference called “Hide/Seek,” organized by the National Portrait Gallery. Wojnarowicz completed work on the video in 1987 after spending several years gathering research material and images in Mexico and Latin America. Dedicated to the memory of photographer Peter Hujar, Wojnarowicz’s close friend and former lover whose death from AIDS marked a decisive turning point in his artistic and personal life, the video is assembled out of a rapidly inter-spliced collection of footage, some intentionally staged, some found and repurposed. Crafted in Wojnarowicz’s signature raw, quasi-punk aesthetic, the video is a discomfiting mélange of quickly shifting images: a white porcelain bowl fills with blood; two hands attempt to sew a bisected loaf of bread back together; the lips of a face are pierced by a needle and thread, sealing up the mouth; a young man removes his shirt, then his pants and underwear. The full-length video also includes harrowing footage of Mexican street life, a bloody cockfight, and a brutal wrestling match: the violence of the filmic cut resonates and amplifies the violent thrust of a proliferation of bodies smashing into each other on screen. (Art critic Holland Cotter has written an interesting takeon the piece for the New York Times‘s Arts Blog). In the version of the video displayed at the National Portrait Gallery, Wojnarowicz’s video is accompanied by excerpts from experimental musician Diamanda Galás’s Plague Mass, in which the singer shrieks verses from the Book of Leviticus enumerating Biblical laws regulating the treatment of the “unclean.”

The Catholic League’s Bill Donohue honed in on one image in particular — a shot of a crucifix and wood-carved Christ figure, blood dripping from its wounds, a black smear of swarming ants covering over its prone body. “It would jump out at people if they had ants crawling all over the body of Muhammad,” Donohue protested in an interview with the New York Times, “except that they wouldn’t do it, of course, for obvious reasons.” Shamelessly insisting that the display of this image constituted “hate speech” against Catholics and Christians more broadly, Donohue’s bizarre logic was reiterated by Rep. Eric Cantor, who told Fox News that the display of the video was “an obvious attempt to offend Christians during this Christmas season.” The video was taken down on November 30, the evening before World AIDS Day.

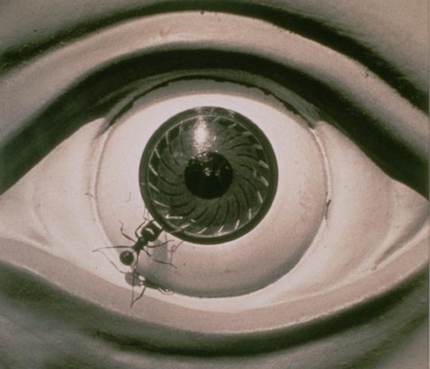

Despite Donohue’s and Cantor’s almost willfully asinine contention that “A Fire in My Belly” is anti-Christian, Wojnarowicz’s video — and indeed his artistic project as a whole — both draws from and radically reconfigures the centuries-old representational tradition of Christian martyrdom in Western art. Wojnarowicz’s imagery takes clear inspiration from both high Renaissance tableaux of Christ’s suffering on the cross and the colorfully gory vernacular depictions of religious figures he encountered while traveling and working in Mexico. The beautifully composed Christ image in “A Fire in My Belly” combines the artist’s longstanding appropriation of religious iconography with another of his frequently evoked subjects: ants and insects constitute one of the most striking formal motifs in Wojnarowicz’s artwork, crawling over the surface of paintings, looming ominously in enlarged close-up photo-collages, and traversing video frames. But ants here also play an important aesthetico-political role: they manifest the artist’s sustained and rigorously developed interest in finding beauty in the abject, the marginal, and the subterranean. Minuscule organisms teeming beneath the surface of the visual world, ants in Wojnarowicz fervent imagination signal a kind of return of the repressed: a simultaneously mesmerizing and repellent reminder of the primordial origins of the social itself. Viewed in this context, the ant-covered Christ is less a desecration than a political intervention, a reorientation of the visual field that lends the iconicity of the crucifixion a newly recharged corporeality.

But what seems to be truly unconscionable for critics of Wojnarowicz’s art is its forceful imputation of the analogy between the Biblical torment of Christ and the contemporary suffering of queer bodies and subjects. Far from a reductive or simplistic attempt at shock value, as Donohue and Cantor would have it, Wojnarowicz’s ant-covered Christ fires on a number of representational and figurative levels at once and becomes the locus for a range of intersecting cultural imperatives. In its abject prostration, the figure calls discomfiting attention to the parallels between Christ’s tribulations and the stigma and paranoia surrounding the queer body during the initial flare-up of the AIDS crisis. Wojnarowicz’s Christ image also functions as a visual reprimand to the viciously disingenuous response of the Catholic Church to the epidemic, and its refusal to countenance the use of condoms to prevent the spread of the disease. Christ, here standing in for the penetrated and vulnerable queer body, bears witness to the damage inflicted by the paranoid fantasies propagated by church, state, and the mass media. Wojnarowicz’s ant-covered Christ is thus simultaneously an icon of queer identification, and a castigation of the institutions and individuals who so uncannily reiterated the humiliations visited upon Christ in response to the threat he posed to the stability of the social order.

Responding to the recent controversy in a letter published in the Washington City Paper, Diamanda Galás herself underlined this point in her inimitable fashion: “What the Catholic League and certain members of the House presumably wish to remove from their consciousness,” she writes, “is thirty years years of death sentences handed down to their parishioners and citizenry, who were told not to wear condoms, and the mistreatment of those stigmatized as miscreants and sinners by their viral status and/or homosexuality and/or status as drug addicts. They wish to remove the UNSEPARATE CHURCH AND STATE conduct throughout the epidemic, which this film articulately reflects.”

* * *

Inevitably, far from eradicating “A Fire in My Belly” from the visual field or the national consciousness, the Portrait Gallery’s action has instead produced what Michel Foucault would call an “incitement to discourse”: suddenly Wojnarowicz’s haunting, beautiful, and wholly unique vision is everywhere, his name making headlines and snapshots from his work traveling widely across newspapers and the web. The Washington Post, the New York Times, and New York Magazine posted links to the banned video on their websites. Expressions of outrage quickly circulated across the Internet — through Twitter, Facebook, and other social media platforms — often accompanied by links to the video’s YouTube page. Transformer, a Washington DC gallery located not far from the National Mall, announced that it would screen “A Fire in My Belly” on a 24-hour loop in its front window until the piece is reinstated at the NPG. In an action reminiscent of a similar response to the controversy surrounding a planned exhibition of Robert Mapplethorpe photographs at the Corcoran Gallery in 1989, a group of activists projected Wojnarowicz’s work on the NPG’s walls. And on December 4, two agitators were detained by police and then expelled for life from the Smithsonian after showing the video on their iPads inside the “Hide/Seek” exhibition itself.

Considering the outpouring of support for the banned video, it would be tempting to conclude that the usual suspects on the Right had fallen for Wojnarowicz’s bait. In seeking to censor his images, it might be argued, Donohue, Boehner, Cantor and company actually wildly increased the visual purview of the work and redoubled its political potency. Wojnarowicz, of course, was no stranger to run-ins with state authority, and cannily used his work’s provocative formal qualities and subject matter in order to promote both his career and the his political agenda. In 1990, he successfully sued the American Family Association’s Frank Wildmon for copyright violation when the AFA used out of context snippets from his work in a pamphlet they circulated to lobby against funding the National Endowment for the Arts. (Interestingly, that case also revolved around Wojnarowicz’s queer redeployment of religious imagery). In one sense, the latest imbroglio around Wojnarowicz’s incendiary images simply confirms the hypnotic power they seem to hold over the would-be moral custodians of the visual field. Certainly as a student of Wojnarowicz’s work and the period in which he lived, it has been perversely gratifying to witness his singular vision return with such urgency to the front lines of the contestation over the questions of sexuality, art, and state power.

But both the censorship of Wojnaworicz’s work and the response it has engendered also indicates — and, perhaps, diagnoses — the pernicious conditions under which representations of non- or anti-normative sexual identities and politics are produced, circulated, and regulated. And the furor provoked by the incident suggests the extent to which ongoing tensions surrounding the inclusion of certain queer people and bodies within the national imaginary are largely played out within the order of “representation” as such. The piece was, after all, displayed in the National Portrait Gallery, a part of the Smithsonian and hence, in a very official sense, an institution whose federally mandated mission is to preserve and visually represent the nation to and for itself. The familiar mantra heard from conservative complainers — that the video was “in-your-face perversion paid for by tax dollars” (as Georgia’s Rep. Jack Kingston would have it) — has simply cemented and reiterated the association between the politics of (visual) representation and the entrenchment of neoliberal economic imperatives at every level of the political system. While the wholesale decimation of public support for the arts and humanities in any form has been a bedrock of the conservative agenda since the Reagan ascendancy, the invocation of queer, “anti-Christian” artwork as a justification for slashing public funding as such has attained scary new mouthpieces in the era of the Tea Party and Sarah Palin. As NPG director Sullivan put it in his interview with the Times, “Obviously the Portrait Gallery is a part of the Smithsonian. It’s just one of many, many players in this new discussion or debate that’s going on in Congress about federal spending, the proper federal role in culture and the arts, and so forth. We don’t think it’s in the interest, not only of the Smithsonian but of other federally supported cultural organizations, to pick fights.”

Beyond the economic register, we might also be prompted to consider the ways in which the contested image of the suffering queer Christ covered with ants — created at the height of one moment of particular “gay panic” — now resonates within the broader context of the ongoing debate surrounding the legalization same-sex marriage and the open acceptance of gays in the military? And what of the heightened national attention now being paid to the vulnerabilities of queer youth to bullying and suicide? The reappearance of Wojnarowicz’s work within the political present serves as a depressing reminder of just how impoverished the vision of queer politics has become since the height of the AIDS epidemic in the US. Wojnarowicz’s (and Galás’s) deeply unsettling, politically uncompromising words and images render even more stark the emaciated political imagination of the mainstream LGBT rights movement. The focus for the past decade on marriage and military rights once again exposes the degree to which the fantasy of the healthy body (most often white, most often male) serves as a regulatory norm for the kinds of citizens deemed worthy of representation and rights (a notion that Jasbir Puar has so forcefully developed in her work on the biopolitics of what she has termed “homonationalism”). Indeed, we should wonder if it was purely coincidence that this controversy erupted the very same week that the Pentagon released a study concluding that the repeal of the Don’t Ask Don’t Tell Policy would not have any significant negative effect upon military readiness.

More distressingly still, certain voices from within the gay community itself have voiced their disapproval of both the display of the video and Galás’s response, contending that both “make us look bad” or “prove [Donohue’s] point.” This anxiety, of course, only confirms the power that privileged modes of visual representation have to determine who and what is deemed worthy of national inclusion. And ultimately it reveals the way certain queer subjects and representations — healthy, aspirationally middle-class, white, and married — are easily assimilable into the discourse of the nation, while the freaks so beautifully invoked in the work of Wojnarowicz and Galás become figured as threats to the coherence and impermeability of the national body itself.

For my part, I wonder if what we can learn from this incident is that the unstinting work of artists like Wojnarowicz and Galás should be viewed not as moribund artifacts from a more radical queer past, but, as José Esteban Muñoz helps us to imagine, visionary invocations of a future whose time has yet to come. In this sense, perhaps we can read “A Fire in My Belly” as a wake up call addressed, precisely, to us–illuminating an alternative route through the treacherous present, and providing an X-ray of a civilization that was, and still is, yet to be.

Leon Hilton is a PhD student in the Department of Performance Studies at New York University.

Image: detail: David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (ant and eye), 1988-89, black-and-white photograph, 20″ x 15.7″