After casting his vote quite early in the day, Yangala Chittiah (pictured above), a resident of Pydipalli in West Godavari, Andhra Pradesh, spent the afternoon waving at voters heading to the polling station dressed as former chief minister YS Rajasekhara Reddy. Photo by @harshavadlamani.

The landslide victory of Narendra Modi’s BJP in the recent Indian elections has created the impression that his juggernaut has swept all and sundry before it. With no party winning enough seats to be the official opposition, the Congress Party dwarfed beyond recognition and regional parties no longer pivotal players within coalition government, this parliament looks radically different from those we have become accustomed to in the last 25 years.

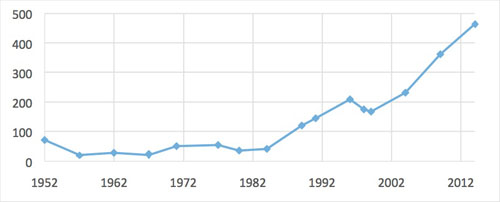

Since 1989, power – both political and economic – had flowed away from India’s central government and towards its states where a variety of regional parties blossomed. As Yogendra Yadav and Suhas Palshikar put it, in this period, “states … emerged as the effective arena of political choice.” Until 2014, political scientists worked with the assumption that parliamentary elections in India could only effectively be understood as the aggregate outcome of multiple state-level contests (see my earlier blog post on this question). This was a period in which regional parties of a variety of hues came of age. Organised around lines of identity (region, caste, language or religion), or frequently as splinters of national (and increasingly also regional) parties, most only won seats or votes in one state within India’s federal system. But taken collectively they had an increasingly formidable presence in parliament reliably winning over 35% of all seats from 1999 onwards and close to 45% of all votes. Their presence meant that no national party since 1989 – and until Narendra Modi’s victory in 2014 – was able to win an outright majority of seats in parliament. Coalition government bringing together national and regional parties became the norm in New Delhi. An increasingly stable alliance system – dominated by the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance and the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance – fell into place from the late 1990s. The possibility of finding a berth within a national coalition government itself acted as an incentive for politicians to form yet more regional parties, often by breaking away from a national party.

Opinions differ on the impact that regional parties had within national governments. India’s last Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh, wondered aloud whether the involvement of regional parties in national coalition governments was damaging the national interest. Sometimes, he said, “narrow political considerations, based on regional or sectional loyalties and ideologies, can distort the national vision and sense of collective purpose.” Others saw the rise of regional parties as a positive reflection of a more decentred polity and the rise of stable patterns of coalition government as an offshoot of the ability of India’s political institutions to flexibly reinvent themselves to embrace the diversity of regional and ethnic identities in the country.

Yet with the rise of Narendra Modi, and a more presidential style campaign, these elections appeared to have more of a national character than those in the recent past. This has been confirmed in the election outcomes with Narendra Modi’s candidature helping the BJP to appeal to new sections and regions of the electorate. For the first time since Rajiv Gandhi’s landslide victory in 1984 in the wake of his mother’s assassination, one national party has won a clear majority of seats without the need to rely on coalition allies (although these haven’t been ditched altogether).

However look closer at the results and the changes to the composition of parliament may not be as radical as they first seem, especially in terms of the balance of support for national as opposed to regional parties. The BJP’s victory – at an all-India level – came as a result of changes within the national party category and primarily the collapse of Congress, rather than as a result of the sidelining of regional parties. Indeed, if anything, regional parties slightly increased their share of seats in parliament. As I show in an article in the Indian Express, the national party seat share has fallen marginally from 63% in 2009 to 62% in 2014. Furthermore, these elections saw a record number of parties contesting the elections – over 450 in total. In the states of Tamil Nadu, Odisha, West Bengal and the newly divided Andhra Pradesh and Telangana regional parties remained dominant, even enhancing their grip on their respective states. Most of these parties – which dominate politics in their states to the exclusion of national parties – are not part of a national alliance. They may become important opposition voices in the course of the next parliament, if Narendra Modi’s proclaimed vision of a “cooperative federalism” in which the national government works in partnership with the states fails to satisfy their interests.

But despite the resilience of these larger regional parties, overall the modal size of regional party in the Lok Sabha is small – 25 of the total 31 regional parties which won seats in parliament, have 6 or fewer MPs. The median party size in the Lok Sabha is just 3 seats. Many of these small parties had agreed seat-sharing deals with the BJP before the elections and are now part of the governing National Democratic Alliance led by the BJP. Major regional parties representing lower castes in the large Hindi-speaking states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar failed to convert votes into seats, as the BJP managed to confine them to their core vote bases and peel away the other voters they had attracted to build broader social coalitions in the recent past. While the Bahujan Samaj Party – representing Dalits or former “Untouchables” at the bottom of India’s social hierarchy – emerged as the third largest party across India by vote share (winning 4.1% of all votes nationally) – it didn’t win a single MP. Thus while “identity”-based regional parties were reasonably resilient in terms of their vote-share, they were less successful at winning seats.

In conclusion, regional parties have not collapsed overall but there has been a shift in the kind of party that has won seats. Parties mobilising narrow social constituencies or reduced to their base – such as BSP – have not been favoured by the first past the post (FPTP) electoral system in these elections, with a shift towards parties espousing crosscutting identities. Small parties have done well in alliance with national parties; this may be something to watch out for in the future – whether the lure of participation in national alliances offers incentives to state-level politicians to break with dominant regional parties to float smaller outfits. We may also see national parties encouraging such breakaways from those regional parties that have remained resilient as a means of chipping away at their power bases. These small parties may be easier to control politically.

The bigger question is perhaps how the non-aligned regional parties will use their position within this parliament, in a context in which there is no official parliamentary opposition. Will a clearer coalition representing regional interests or the rights of states emerge? There are few consistent signs of this yet, although these remain early days. Those regional parties that have the largest proportion of seats are “regional” in identity but inconsistently regionalist.

Louise Tillin is a political scientist King’s India Institute, King’s College London, who works on politics, federalism and the political economy of development in contemporary India. Her book, Remapping India: New States and Their Political Origins (London, Hurst & Co; New York, Oxford University Press, 2013; New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2014), looks at the territorial restructuring of the Indian federal system.