Years ago, at a conference, Tavia and I talked about what to do in our responses to the theoretical turn to negativity in black studies. The sound of this turn was roaring all around us, and we had to shout above the storm. It was churning with particular force in the hallways of the conference hotel, picking up graduate students as it went along. Some of us escaped this academic tempest in a teapot, but we are all still soggy and damp from it.

Some of us were open to the corrective the impetus suggested to liberal humanism in the realms of critical theory and activism. But it seems to me that many versions of this turn to the negative gobbled up subtleties, complexities, doubts, ambiguities, liminalities. All or nothing, in or out, for or against, were its starkly antagonistic terms. Nuance was for pussies. Only the strongest theoretical pugilists need enter the ring. But some of us are not afraid of death. We want to revel in the afterlife, the “dark time” of our existence. In the years that followed, we found other compelling areas to concentrate within. But I open with what has lingered in both Tavia’s and my work: the question of how to address the practices of black, and queer, life and liveliness evident in the nooks and crannies of an apocalyptic world.

What could black and queer studies do in conversation with new materialisms? Studies of time and temporality? Queer futurity? For these and other questions, Nyong’o develops a nuanced, complex, subtle theoretical model to think with. In his new book, Nyong’o introduces this model and calls it afro-fabulation. Nyong’o’s thinking is expansive and inclusive; like his intellectual range, the term is capacious. It is plastic, refusing to be still. He does not seek to refute or debate with the turn to negativity in black or queer studies; rather than participating in binary or confrontative formations of academic engagement, Nyong’o insists on multiplicity, the proliferation of possibility.

Afro-fabulation is fundamentally reinterpretive and transformative, as it changes shape in each of his analyses. He refuses to “coin” the term, turn it into intellectual property, but instead uses it as a gathering point to think about and value black and brown, feminist, queer and trans aesthetics, and the ways these aesthetic practices reinterpret and transform the core dominant and dominating ur-narratives, which are, for us, fictions of a nightmarish kind. One form of fabulation Nyong’o calls speculation, a “reaching toward something else.” Nyong’o writes:

Black feminist and posthumanist acts of speculation are never simply a matter of inventing tall tales from whole cloth. More nearly, they are the tactical fictionalizing of a world that is, from the point of view of social life, already false. It is an insurgent movement…toward something else, something other, something more (6).

But just because the world has been falsely rendered does not imply there is an authentic core to uncover, or that we bear the “burden of truth telling” (51). As fabulists we use, as Nyong’o quotes Gilles Deleuze, the “powers of the false” (51). The aim is not to reanimate the flabby concept of agency–for the point is not individual autonomy, but disruption and collective movement. The point of afro-fabulation is not centrally ontological; it isn’t reaching for new ways to think about the sovereignty of self or species. It remains suspicious of humanism, but is not hubristic enough to claim that, by sheer force of will, we could perceive completely outside of a humanist episteme.

I am picking out two areas of Nyong’o’s exploration to consider here: time and representation. Time has been the choice concept framing a similar a turn to negativity in queer studies. Queer studies scholars including Elizabeth Freeman, Heather Love, and Jack Halberstam have explored other ways to think about time, and the term futurity has been a gathering point for the challenge to a totalizing urge within this turn. Nyong’o is also thinking about time, but not in terms of further developing the concept of futurity. Instead of ways to render a future, Nyong’o proposes we consider time itself, as ordered differently. Time is what story needs, as he argues, but, inspired by Henri Bergson’s concept of duration (durée), Nyong’o calls time both “tensed” and “tenseless;” that is, composed always of “coeval presentness” (9-10). Stories are the directive flows we select from the infinite eddying currents of la dureé. If we think of time in that way, we need fluid “insurgent movement,” rather than linear, chronological corrective. Bergson’s model is concerned with memory, how a story orders itself. In Chapter Four Nyong’o uses a model of collective memory that “foils the attempt to cohere the narrative of the past into a single, stable, linear story” (99).

His read of Kara Walker’s A Subtlety demonstrates his approach, which does not seek to recover her installation at the Domino Sugar Factory nor condemn it. His analysis shows the delicate quality of his touch, as it lays out the questions the piece raises regarding the range of possible ways to think about the author’s commitment and the audience’s responses/participation. Everyone is implicated in his thoughtful exploration, but no one blamed.

Nyong’o is interested in the image, in the relationship between performance and the camera. What I find particularly useful in Nyong’o’s framework is its refusal of a representationalist politics. He avoids the entire lexicon in black studies surrounding the search for representation on one hand, and the desire for freedom from hypervisibility on the other. He points out the importance of collective recognition, and does not seek to correct how we appear in relation to the normative terms of legibility. In his Introduction, referring to Wu-Tsang’s film for how we perceived a life, Nyong’o writes:

[the film] explores the need for black, brown, feminist, queer and transgender participants in the ballroom scene to be seen, heard, and felt while resisting the temptation to accept visibility under dominative constraints as a fulfillment of that wish (8).

In Chapter Two Nyong’o explores the film Portrait of Jason through a black queer lens and posits the idea of “archival opacity.” Nyong’o uses José Muñoz’s concept of reparation, which is distinctly not the same as restoration. The subject is not restored, like a film, by some new critical focus. Nor is the subject erased by any new theory of blackness as nothingness. Instead, the subject remains shadowy, doubled, indistinct, which implies a certain freedom, a “dark fabulation” (49).

What makes Nyong’o’s work so useful is it considers things, rather than assesses them. He leads with a sense of what is politically urgent, but holds tension in his analysis, allowing multiple stories to unfold. This is vivid for me in his chapter on Beasts of the Southern Wild, which I could never stay calm enough to read as thoughtfully.

Soon after our conference conversation, Nyong’o was invited to go toe to toe with another scholar on the subject of blackness and negativity. But this is not Nyong’o’s style. He does not join a side in a tussle. He does not shape his study according to the existing terms of the debate. Nyong’o’s afro-fabulation, then, has a potent opacity that welcomes a fluid multiplicity, a flow of possibilities that make any reductive binary thinking impossible. His work models a kind of queer approach that refuses the masculinist fabula of the intellectual duel.

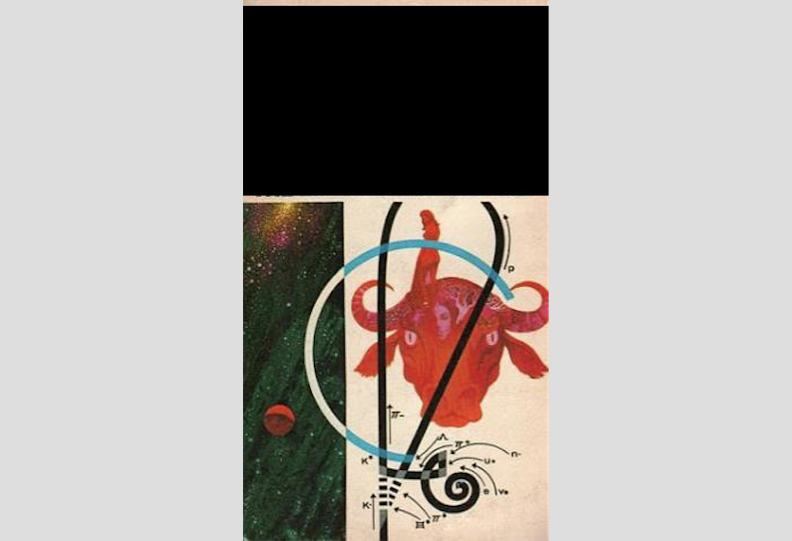

Cover image: The Einstein Intersection, by Samuel R. Delany, 1967. (Cover detail.)