It’s hard to say that someone had a bad year because they made fewer millions than usual. And it’s even harder to pity 50 Cent under any circumstances. But still, 2009 was rough on the hip-hop superstar otherwise known as Curtis Jackson. It ended with his latest album, Before I Self-Destruct, deservedly yielding the kind of sales numbers that inspire bad title-related puns. And it began with rap’s most meaningless, inane and stage-managed beef yet, a feud between 50 and purported coke kingpin Rick Ross. Ross flailed around accusing numerous people of being gay. His rival MC mocked Ross’s past career as a correctional officer, apparently reasoning that a rapper who never shoots a music video without a huge yacht in it and claims to be owed many favors by Manuel Noriega would be nothing without his aura of gritty realism. After many crudely animated web videos, the spat was inconclusive and embarrassing–for anyone who’d paid attention to it, but mostly for 50, who built his career on moments of sardonic malice. He was the gangsta underdog who used an early single to outline how he might rob various musical celebrities, the guy mean enough to euthanize Ja Rule’s career with a few disses. The problem with cultivating your own reputation for ruthlessness is that people begin to presume results. One can giddily loathe the New York Yankees when they’re winning, or egg them on against a mutual enemy. But a rich bully who becomes unimposing is no use to anyone. And when 50 Cent sneers “I’m going to fuck up your life for fun,” as he did to Rick Ross, you expect something close to supervillainy. He didn’t even seem to be having much fun.

After an ambush shoots up a car, a precious skull is stolen by one of those terrorists who just happen to look like video models. 50’s quest to get it back takes him across and beyond a chimerical city, a besieged pastiche of Baghdad, Dubai, and Afghanistan. The game situates bombed-out streets and ruined highways next to massive construction sites and shopping malls, with mountain fortresses only a short drive away. Despite this, Blood on the Sand‘s environments are strangely context-free: the soundtrack’s omnipresent air raid sirens seem to be blaring from nowhere in particular. Curtis tangles with corrupt security contractors – including a black American mercenary named Carter who bears a passing resemblance to Jay-Z (born Shawn Carter) but he never sees a soldier. On 50’s last great song, 2007’s “I Get Money,” he dissipated the tension between street records and boardroom deals by treating his own Vitamin Water-sweetened riches with gleeful irreverence: “Have a baby by me, baby, be a millionaire / I’ll sign the check before the baby comes, who the fuck cares.” Blood on the Sand does the same thing by embracing its hero’s latest, least interesting persona in the most kinetic way possible. Listening to a humourless, victory-obsessed mogul is a bore, but shooting through this imperial playground as one is a perverse thrill. The musical monotony of dispatching generic foes becomes addictive compulsion when they form waves of enemies gunning for your avatar.

Though it was released on the Xbox 360 and Playstation 3, the latest consoles that money can buy, Blood on the Sand is a conceptual throwback. When we hear the phrase “music games” today, we probably think of the phenomenally successful Guitar Hero and Rock Band series: games where you use specialized instrument controllers to approximate hit songs. But the high sonic fidelity required to do this only became available a few years ago, and even the Dance Dance Revolution series–which combines cheesy Europop, touch-sensitive mats, and foot-eye coordination to get nerd asses shaking–is no more than a decade old. Before then, music games simply pasted their licensed protagonists into various existing genres. The results were almost universally terrible. If anyone refers back to them now, it’s usually as a cheap source of internet lolz–like Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker, the Sega Genesis beat-em-up where MJ rescues missing children from the sinister clutches of a Mr. Big. Fans seduced by the promising title of Prince Interactivewere surely disappointed when they ended up solving a bunch of puzzles inside a simulacrum of Paisley Park. Gimmick met gimmick in the Sega CD’s Kriss Kross: Make My Video. There were not one but two crappy Kiss games. And the arcade shooter Revolution X took place in a dystopian future where rock and roll is banned, Aerosmith has been taken hostage and only you can save the Princess, Steven Tyler. Because it was 1995, this entailed firing razor-tipped CDs at ninjas inside pixelated strip clubs.

Unlike, say, Wu-Tang: Shaolin Style, Blood on the Sand broke from tradition merely by being a pretty good video game about a musician. It’s strangely logical: both gangsta rap and virtual violence were transgressive enough to inspire moral panics.

Blood on the Sand is structurally similar to many other recent third-person shooters, especially the popular Gears of War series. You have an arsenal of guns and grenades to fire at enemies while ducking behind cover; there are various close-quarters melee attacks; and occasional vehicle missions provide a change of pace. What distinguishes 50’s game is that everything in the environment is fungible. Slaughtering enemies, destroying the décor, collecting hidden G-Unit memorabilia and completing certain optional tasks all reap piles of cash. The more efficient Curtis’s murdering, the greater his reward; when you chain kills together in quick succession, the lucre multiplies exponentially while exclamations like “MASSACRE!” and “KILLING SPREE!” pop up onscreen. The war chest can be exchanged for new capabilities, such as more advanced close-quarter executions or taunts. An entire controller button is dedicated to the taunts, and tossing off some well-timed disses after gunning down a foe will result in yet more money. They’re not exactly witty–you’d hear better punchlines on any Cam’ron record–but the feature is still a clever approximation of the verbal dexterity that rap demands. Curtis also has a meter that fills up as he shoots or gets shot without dying. Trigger it and you enter “Gangsta Mode,” which slows the surrounding world to a glacial and easily targeted pace.

Hip-hop has engaged with the Islamic world long before this game from myriad perspectives, piety being only the most common. Other examples include the Dubai-worthy crassness of Busta’s recent “Arab Money,” Dipset’s bipolar Al-Qaeda fixation, or the harem-porno beat of 50’s own single “Candy Shop.” Blood on the Sand, however, might be the first one animated by amoral nihilism. I don’t want to exaggerate the storyline’s grimness. This is still a game in which Curtis, after asking where to track down a particular contact, is told: “You can find him…in the club!” But it’s also a game in which nearly every character emphasizes how untrustworthy everyone else is. The guy who booked 50 sells him out, enabling you to fulfill the musician’s fantasy of firing a rocket launcher at a crooked promoter. The sole female character betrays our hero multiple times.

The former US government operative, now a mountain warlord gone native, also covets the game’s central gore-flecked treasure. In other words, Curtis discovers that his fellow Americans are even more mercenary than the locals, and the only people he can trust are his crew — along with the 50 Cent stan who runs a local strip club. It’s a very old tale about the supposedly corrupting temptations of the Third World, though the fact that most of the game’s cast seem like transplanted gangsta-rap archetypes scrambles the Orientalism somewhat. The action-movie exploits of a Rick Ross seem less outlandish next to the reality of Blackwater or Executive Outcomes; indeed, the former are now popular soundtracks for war itself. The urban theorist Geoff Manaugh appropriated a loaded phrase from American military planners to consider “feral cities,” places where natural disaster, government breakdown or colonial occupation create legal and architectural chaos, possibly followed by rebellion. Manaugh suggests that urban infrastructures might be “feralized” in self-defense, before an impending attack rather than in the devastating aftermath of one: insurgent cities? The Paris Commune, Mumbai slums, enclaves of fanatical libertarians or Thatcherized public housing could all be described in these terms. Blood on the Sand‘s unnamed setting is a more cartoonish example of the concept in polygonal space.

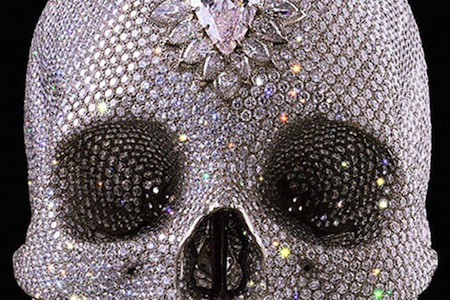

In a post about the game, the widely read video game blog Kotaku described it as “Rappers do Gears of War while hunting down Damien Hirst sculpture.” The joke was telling, and not just because Blood on the Sand‘s developer is based in Britain. The sculpture in question is For the Love of God, a platinum cast of a human skull encrusted with 8600 diamonds that artist Damien Hirst displayed in 2007. It’s almost radically tasteless, in the sense that its meaning is primarily determined by its monetary value. The initial asking price, 50 million pounds, had anticipated unreal economic boom rather than financial crisis. Hirst made a striking comment during the skull’s unveiling. He confessed to fearing that the finished artwork would look like something worn by Ali G, the ridiculous-jewelry-loving gangsta wannabe created by comedian Sacha Baron Cohen. Even a panderer on Hirst’s scale would rather associate his sculpture with classy religious icons than some rapper’s cheap, gaudy bling.

The snobbish class distress was unfounded anyway: MCs are already wearing postmodern meta-commentary and art-school surrealism around their necks. Consider T-Pain’s latest piece, or every piece of ice Gucci Mane owns. And the artist’s unease revealed a larger aloofness. His skull enshrined diamonds as objects of reverent fascination or antiseptic musing, but in most of the world–and in Blood on the Sand–they’re rocks that people slave or kill for. As Soulja Boy, a rapper who couldn’t be more unlike 50 Cent, put it: “I’mma die for this gold.” The recent study Games of Empire by Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter notes that game consoles themselves are containers of economic exploitation. Produced using rare minerals that are often sourced from war zones or dictatorships, they return to the Third World as “cauldrons of poison” inside vast garbage dumps once they become obsolete. According to Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter, when the frenzied launch of Sony’s PS2 inflated coltan prices exponentially in 2000, ore-hungry militias and mining companies used prisoners of war, children, and sometimes guns to extract their quarry from the Eastern Congo’s chthonic open pits. In this grim context, Curtis’s characteristic flippancy might be a subversive act. When he finally gets his damn skull back during the game’s final cutscene, he puts it on his dashboard, sticks a cigar in its mouth and uses the priceless artifact as a hood ornament.

In 2008, during a G-Unit concert in Angola, a man wearing a yellow shirt leapt onstage and snatched 50 Cent’s chain. The aftermath didn’t involve any rocket launchers or slow-motion gunplay: the teenage culprit was actually turned in to the authorities by his parents. In a little parable of the creative exhaustion afflicting many best-selling gangsta rappers, the shaky video of the event was more dramatic and surprising than 50’s contrived beef with Rick Ross.

I take no joy from that. There’s so much formal invention, damning testimony and galvanized force squeezed into the genre’s history, and the possibility that the future of hip-hop belongs to Drake or Charles Hamilton is depressing. In recent years, though, it’s seemed like the only path to popular success is roleplaying a hypercompetent paper-stacking badass, and I welcome the end of that archetype’s vicarious ubiquity. It’s a better look on virtual avatars anyway. 50’s lyrical menace no longer convinces, his wordplay sounds like work, but he’d make a great space mercenary. If Blood on the Sand is any indication, he’d be more relevant as one too. (And his funniest lines lately have been tweeted rather than spoken.) The yacht rappers’ commercial domination came to eclipse more arresting variations on the fundamental gangsta concerns of poverty, crime, fraught solidarity, and penal oppression–such as Z-Ro, the Houston MC who occasionally reminds you that he’s packing amidst deeply emo songs about his drank addiction, his romantic frustrations, and his loneliness. As the number of platinum-selling rappers of any kind becomes smaller and smaller, in an industry no less imperiled, unfamiliar hip-hop personae are getting words in. The average musical hegemony is fleeting compared to the geopolitical ones. There are skaters in skinny jeans rapping, like L.A.’s jerkin’ crews; white rednecks rapping, like Alabama’s Yelawolf; women who could fit into Chuck Jones cartoons rapping, like Nicki Minaj. There are middle-aged rappers secure in their years and teenagers like Soulja Boy or Lil B channeling the internet’s unfiltered id. That Angolan kid could be making a mixtape right now. While Xboxes remain too expensive for most Africans (and are the opposite of leisure, for certain labourers at gunpoint), basic recording technology is increasingly affordable, salvageable, or downloadable, with the continent’s hip-hop productions proliferating accordingly. Curtis lost his chain, but we have a vaster sonic world to win.