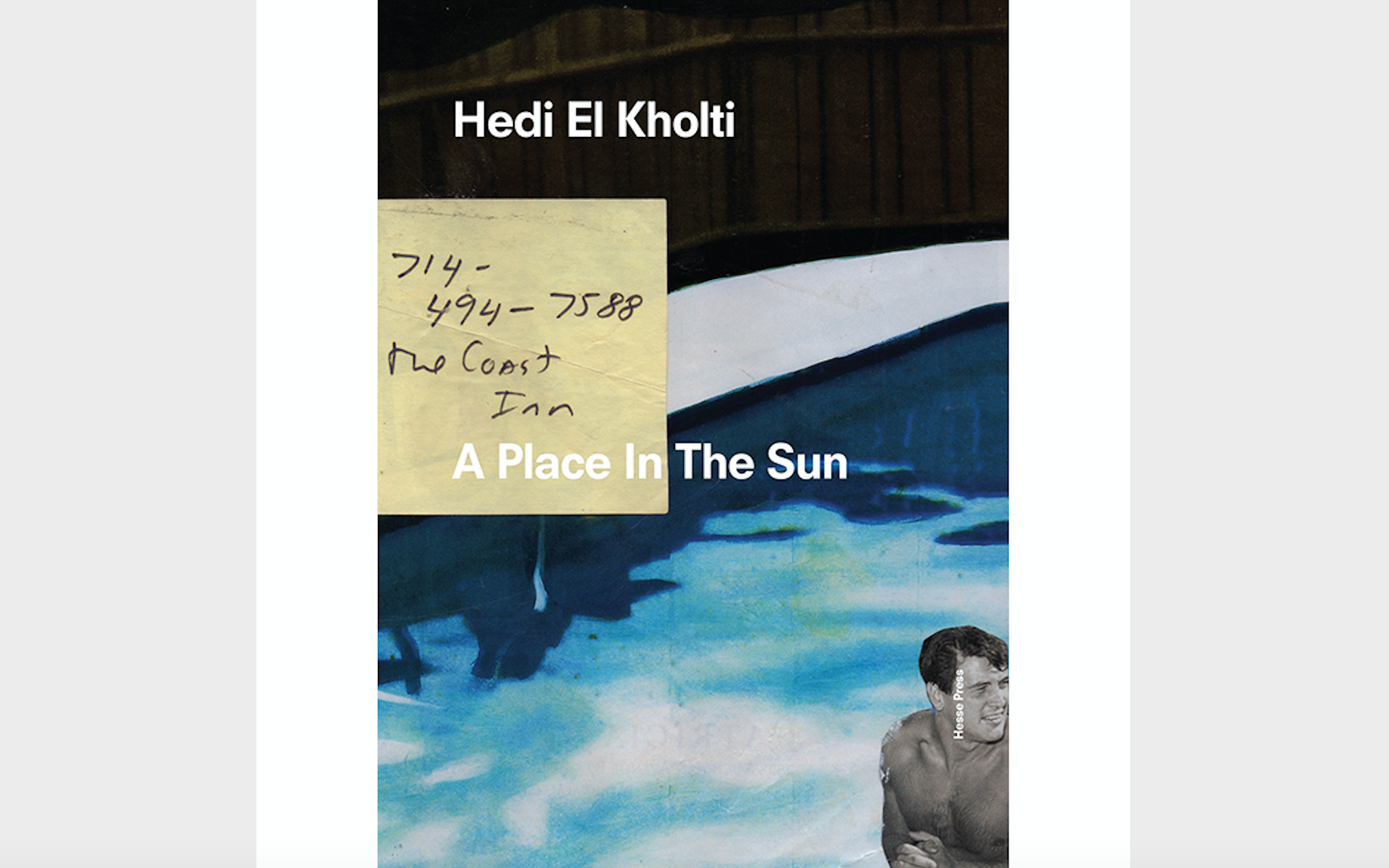

Hedi El Kholti’s book of collages, A Place in the Sun (Hesse Press: Los Angeles, CA, 2017), collects images of subversive beauty, drawn largely from magazines, and transforms them as they play off each other, creating resonances over a wide field of knowledge; in this way, the book is a kind of visual testament to freedom and the intellectual life. Collectively, the images are like a secret history of alternative thought in music, film, and books. Images fill up the early pages to excess; he uses radiant colors, often bordering on a neon brightness, or lurid tones, or occasionally, black and white, to create a kind of strobe effect. The reader is plunged into a world where anything can happen and it’s like you’re with your friends (Genet, Burroughs, Crowley, Rimbaud, Proust, Bresson, Tom of Finland, Walt Whitman, and Jack Smith) and you’re dancing, and Lou Reed is in the audience and you’re drinking and the you feel the pill take effect, and perhaps, you’re on the way to blowing your mind and you can’t wait for the mundane world to change. It’s 3 a.m. and you’re on fire. In A Place in the Sun, Nico shares a stage with David Bowie, and Last Year at Marienbad is on double bill with Visconti’s Ludwig, and there is also a late night showing of Harry Smith’s films. These images from films, and of musicians and of the covers of books, evoke an alternative universe that celebrates diversity and risk. The men and women in the experimental theater of the image are either nude or decked out in glitter or military uniforms or fabulous costumes; they are not so serious that they don’t know how to laugh; the game of desire and power is played out in these images. And books by Bret Easton Ellis lay on the table alongside books by Mishima. Disparate images are fused by the alchemy of El Kholti’s art.

A Place in the Sun is a personal work; the collages act like a journal that traces the artist’s encounters with an alternative culture over the years. The images are sometimes violent but more often ecstatic, or a mixture of both. He freely associates images of pleasure and sex, along with images of writers and musicians, crossing over centuries and creating, in a sense, an unbounded universe where adventure and risk lead to discovery. The book is also a catalogue of dream states: in one collage, for instance, Burroughs and Gysin stare at the famous dream machine, while two naked men wrestle and kiss in the same collage, Jacob wrestling with his angel. But on the facing page, the image of a skull and Time stand above an image of two men having sex with the caption “golden boys.” The images that associate Death and gay sex recall the time of AIDS. Death undercuts the Dream. Indeed, the tone of many of these collages is one of loss. The next-to-last collage uses an image of Gavin Hamilton’s Where are the Dead? But there are also images of flowers in bloom, which seem to suggest rebirth and transformation. Associated with the sun, the phoenix rises from the ashes.

The alternative culture also has its alternative spirituality: we see images of the I-Ching, photos of Aleister Crowley and Madame Blavatsky. In one collage, there is the image of a man being consumed by a kind of spiritual fire, with a crescent moon on his head, and to his left, a pyramid with two burning holes on its face, which seem like eyes. A blue pyramid appears on the facing page, where a blindfolded woman is steadying the planchette on a Ouija board. Collectively, these images evoke an alternative spirituality with regard to sexuality and desire. Alternately, figures appear in desolate landscapes, as in one collage, which contains a single lighthouse, in a field of ice where a masked figure is standing. There is a sense of isolation in several of the collages while others are dizzyingly excessive. These collages remind me of that feeling you get, in the early morning, watching the sunrise, walking home after spending all night at a dance club (early 90s), slightly drunk and dazed, remembering the wild night; you’re in an alternative space, even for a brief moment, and it seems the world is different and so are you. And then, unable to sleep, you read all day long until the night returns.

A Place in the Sun is an intellectual history in images of the avant-garde in music, film, and literature. I was reminded, when viewing the collages in the book, of all the nights I spent at the Maya Deren theater at Anthology Film Archives when I was a teenager, absorbing experimental films, or searching out the original drawings on the Grove Edition of Jean Genet’s novels, or reading Proust one summer, or getting a VHS copy of Harry Smith’s Heaven and Earth Magic, or the first time I saw Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures, or my first encounter with Rimbaud’s poetry, or Burroughs’ novels, etc,. etc. The book evokes a certain artistic temperament that seeks risk in their readings and in their choice of films and in their lifestyle, in the belief that Art and total experience can revolutionize the mind. El Kholti’s vision is a utopian one, where reading, viewing films, listening to music, and seeking out experiences that alter perception, can transform consciousness and lead to a new vision of the future. Looking through the book, I thought of this quote by the wonderful collage artist, Jess: “It was the variety of existentialism that emphasized alienation, and risk, with its alternate possibilities of despair or total experience, either of which might end as total insanity, but either preferable to the rationalistic traditions which had produced such insanities of its own as wars, prejudice and little houses of death in suburbia.” And so we can all find our place in the sun. These collages are a testament to its existence.