Gabrielle Daniels’s new book Something Else Again: Poetry and Prose, 1975-2019, was recently published by Materials / Materialien in London and Munich and by Dogpark Collective in the US. Daniels’s essays, stories, and poems have appeared in the print and online magazines Big Scream, Equinox: Writing for a New Culture, Kenyon Review, Open Space, Poets Reading the News, Rigorous, San Jose Studies, Silver Birch Press, Sinister Wisdom, and Soup and in the anthologies This Bridge Called my Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, edited by Cheríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa, Sister Fire: Black Womanist Fiction and Poetry, edited by Charlotte Watson Sherman, Another Wilderness: New Outdoor Writing by Women, edited by Susan Fox Rogers, and Writers Who Love Too Much: New Narrative Writing 1977-1997, edited by Dodie Bellamy and Kevin Killian.

This interview was conducted in the summer of 2021.

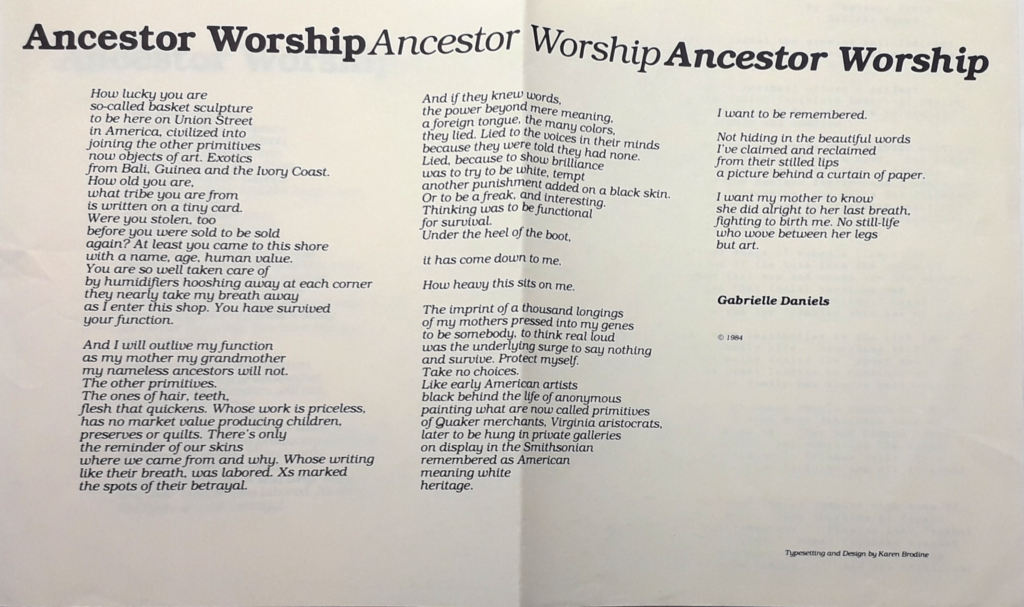

Gabrielle Daniels, “Ancestor Worship.” Broadside designed by Karen Brodine, 1984.

Jamie Townsend: Hi Gabrielle, thank you for taking the time to speak with me about your new book: Something Else Again: Poems and Prose 1975-2019.

Your work has a very complex and nuanced exploration of female embodiment and sexuality across racial lines. It often addresses interracial love and lust in a way that asks indirect questions about the reader’s assumptions. I’m thinking of the first section of Sugar Wars where you write “… he in a wonder when I get on top of him, slide into him. I forget, and then he remember he a white man.” Until that moment I didn’t think of Honore as white, and when I read this line it schooled me on my lack of perspective, my blind spots. Can you talk a little bit about writing interracial love/lust stories.

Gabrielle Daniels: You have to have the dream first before you put can put it down on paper. I think that I was six before it came together for me. Tab Hunter had a short-lived TV show in the late fifties, early sixties. In the days when the networks showed summer repeats, I saw him dressed in a tux with a smart hat perched suggestively a la Sinatra, leaning against a lamppost, crooning some song. I must have been entranced because I recall hearing myself inside saying, I want him.

It wasn’t his blondness that drew me, wanting to make six-year-old love to him. He wasn’t like the white men and boys that I had seen on the news and on the streets of New Orleans, ugly and red-faced with anger, bellowing about segregation now and forever while Ruby Bridges integrated William Frantz. I didn’t know at that time that he was a closeted gay man or why he would disappear from view until the 1980s. He was just a different white man. He was out of the ordinary. And I wanted to experience that difference.

I also have to mention the interracial couples and parents that my family and I met as neighbors in Lower Haight flats and among tract homes in East Palo Alto. They impressed me. John was Black and a MUNI driver, and Mary, white, was a saleswoman at Macy’s. I am not sure whether they were living together before marriage or not, because it was the early sixties, and the Supreme Court had not yet banned the states from declaring interracial marriages illegal. I don’t know how they met. The apartment house kids, including myself, liked them. John knew how to skate and once swung around all the kids that had gathered to see him skate. When we moved to East Palo Alto, John and Mary would visit us in their sporty MG. Once, I took Mary to my elementary school, and as we walked home, she told me that she wished she had a little girl like me. I had never been close to a white woman before, as a teacher or as a friend, and I wished she would take me for her little girl.

Walt and his white wife lived next door to us in East Palo Alto with her three blond children from a previous marriage with a white man. Gary, her son, was nearer my age, but he attended Green Oaks, the junior high next door to my elementary school. Of course, I fell in love with him, and jousted with plastic baseball bats with him, in what kids would call “love taps,” and he would lay his head on my lap while we watched TV at his house. Walt’s wife later gave birth to a brown-skinned, curly headed little boy the neighborhood kids called Jose, because he was closer to looking like a Latino than a Black or white child. I had never seen anything like that. She was pregnant again before we left East Palo Alto, but we lost touch with the family after we moved back to New Orleans when my grandmother died. Once when my grandmother would visit us, she would stare through the window at Gary and me as we played, and when I saw her, it made me feel very uncomfortable.

I heard a story while listening to grown-ups that Walt and his wife finally divorced, and supposedly, when adults asked Gary who he wanted to live with after the split, he picked his stepfather, Walt. Walt had a bunch of relatives who had boys who lived in the East Bay. They were kind, but firm towards him. He minded his stepfather and did not, as far as I knew, harbor any resentment towards him. Someone guffawed that the boy wanted to eat; but the teller said that wasn’t the case at all. I have wondered whatever happened to Gary. Who knows, he’s probably a Trumper now.

It wasn’t until I was about thirteen that I began writing about a black Vulcan queen who gets the Enterprise to intervene in a civil war between her and her usurper half-brother. Yes, you could call it fan fiction because I was into Star Trek and Mr. Spock. I know now that I wasn’t alone in visualizing a black Vulcan, but this was 1967, and Black Power had superseded the Civil Rights Movement. Spock was my refuge at the time. I liked seeing him and Uhura interact, and from what I have read, that respect carried through in real life. Unfortunately, my mother got hold of this little unfinished manuscript and in a kind of ritual, made me throw it away in the garbage can. Later, I saw it there in the little light that night afforded, and I rescued every page even though a couple of pages were dripping with salad dressing. And I cleaned it up and hid them.

Fast forward to high school, where I was part of a little circle of girlfriends, Sharon, Liz, and me. Sharon was in my journalism class and wanted to become a writer. So both of us expanded on our love of fan fiction, this time using other models from TV and from real life. She liked an Italian American shoe salesman at Macy’s. I liked Kid Curry on Alias Smith and Jones. If we couldn’t make love to them in real time–while admiring them from afar–we could do so in our dreams and in the pages of our binders. This time I learned how to hide my stories in progress in among my books and in my tabbed homework, and my mother didn’t find them. We would swap stories and gather later for fun and to talk, and we would dream. Later, while we were in college, Sharon would renounce that period in our lives, that she had given up finding a white man to be with because, paraphrasing her words, too few of them love us. I decided not to give up, even when my experiences being with white men weren’t positive as yet.

It wasn’t that I “hated” Black boys and men. I grew to like some and grew to dislike others. However, they weren’t looking at me, even in college. They were looking at other girls and women of color, or white girls and women. I was too studious, and I wanted to go to and experience college. Besides, I’d seen enough pregnant girls leave school, only to bring back the baby in a buggy to show off for a day, and then disappear.

I wasn’t always reading junk from Jacqueline Susann or from Sergeanne Golon, a husband-and-wife team who produced the Angelique novels. I was trying to find myself in novels about white men and Black women. I read Lillian Smith’s Strange Fruit and shared with Sharon and Liz Kyle Onstott’s sensationalist novels from which the movie Mandingo sprang. (I also read his co-writer Lance Horner’s book on the gay emperor Elagabalus, Child of the Sun.) I also managed to find Gunard Solberg’s Shelia, about a young white man’s obsession with a Black middle-class woman. The most entertaining novel I found was Donald Westlake’s Up Your Banners, a dramedy about an unlikely relationship set during the neighborhood school battles in Brownsville, New York. It was the first book I read where the white man and Black woman headed off into the sunset, come what may.

Then when I discovered Black women’s novels, I came across Paule Marshall.

JT: Another piece in the collection, “Our Nig,” is a vital piece of scholarship that details the previously overlooked “first novel written by a Black American woman” and examines the retroactive building of literary histories around the idea of what stories should be told as well as how they should be told. You talk about “the truth of her own life” which resonates powerfully with your discussions of censorship (both within and without marginalized communities). How did you first encounter the text? Did reading it shift your own writing practice?

GD: I came across Our Nig during my stint doing book reviews for the San Francisco Chronicle. I was assigned to write the article. The interracial aspect of the book fascinated me, not just because of the relationship between Frado’s parents. More importantly, the book claimed that white Northerners could be as cruel towards Blacks as white Southerners. While slavery was outlawed in many Northern states, indentured servitude was not. In Frado’s case, there wasn’t a difference between them.

There have been more examinations of Harriet Wilson’s novel since I wrote at length about it, particularly Lois Leveen’s “Dwelling in the House of Oppression,” which suggests that Frado’s inability to fit in the Bellmont environment also framed her sense of self. Hannah Miller’s 2016 paper, “Whiteness: The Real Intermediary Agent,” in which Miller reveals Wilson’s penchant for “ghosting”—disembodying and embodying–her character. P. Gabrielle Foreman has done studies connecting the names and places indicated in Our Nig. I haven’t yet seen anything suggesting as I do that any of the white males in the Hayward family (the real-life Bellmont family) had a relationship with the young Harriet beyond what was presented in the novel as a sentimental respite. However, I still think Frado’s obsessive feelings focused on James’s dying are too strong to be overlooked. One thing I know about abuse is that it can take on several dehumanizing aspects, and in Frado’s case, it would be focusing not only on her working day and tasks, but also her developing as a woman physically as well as mentally. The absence of these and other portrayals makes me feel that Wilson did a lot of scrubbing about the nature of her relationships with the male Bellmonts. The subtitle of Our Nig “[…] showing that slavery’s shadows fall even there,” makes me think that the “shadows” are still unspoken or hidden in the North, especially with the proliferation of mixed-race people in New England

The novel that truly “shifted” my writing practice was Paule Marshall’s The Chosen Place, The Timeless People. It was epic, rich in everything that needed to be said. It brought together politics, color, gender, sexuality, all of which culminates in the relationship of Saul Amron and Merle Kinbona. Marshall had me floored, even more than Morrison. It made me want to create something just as expansive, and just as accessible.

I try to read The Chosen Place, The Timeless People at least once a year, just like Jane Eyre and Pride and Prejudice.

JT: Tell me a little bit about the history of your novel in progress (excerpted in the collection) “Sugar Wars”? How did the project begin? Where is it going?

GD: I was already working on pieces of a family epic in the early 1980s, but while waiting for a flat to become available at a friend’s house, I happened on an article in the periodical Southern Exposure. It was the story of how black and white sugar cane workers organized in the fields of three sugar-producing parishes in Louisiana and struck against poor wages and working conditions in 1887 and how the nascent union all came to nothing when the sugar planters use federal troops, vigilantes, and later entrenched white supremacy to crush it. Of course, uncounted scores were killed. Some were even marched into swamps and shot to death. My heroine came from that article. Mattie is ten at this time; her parents are shot and drowned, and these two events account for her conservatism and her hatred of her guardian, Dam Rissa. Clarisse Prevost, who is not Christian, was a union supporter, and alive.

In her need to blend into black people, and to get away once and for all from Dam Rissa, who is a voodoo practitioner and healer, Mattie steals a man who was meant for someone else. He’s a minister, Robert Gibson, engaged to her first best friend, Marilla. Mattie achieves it using voodoo, the very thing she hates about Dam Rissa. Her elopement with the minister sets into motion a lot of things that she hadn’t bargained for. Especially when she finds that she’s not fit to be a preacher’s wife, and that his flock distrusts her. Then, during the upheaval engendered over the Robert Charles incident, a white man named Honoré suddenly becomes attracted to her while he and his friends are looking to string up any black man with distinct, strong features who looks dangerous.

Mattie’s narrative goes back and forth, between 1900 and 1917. She is telling her story to Marcus Christian, an interviewer with the Colored Federal Writers Project in New Orleans, in 1939, just before the Project folds, the New Deal ends, and the Second World War begins. She tells it in a way many black people could not. In exchange, she gives Marcus Christian a piece of his own family history: that she saw his father among the cane workers. She is a witness to the end of a dream, and also being a fugitive and a survivor from vigilantes. I think that we are all touched by history in some way, even ordinary people.

And we were also touched by magic. The Bed is also a character in the book; it is a living tree that turned itself into a bed and was able to “speak” after being blessed by Marie Laveau the night before Clarisse Prevost becomes the placée of Lothair Lafontant. And it is inherited by Matilda and then her daughter Ruther.

Matilda is the name of my great-grandmother who gave birth to my grandmother Ruth, the Spiritual Church minister, and my handsome and very light-skinned great-uncle Robert. Ruth and Robert are the twins in the story, although in real life, Ruth was Robert’s darker younger sister.

Mattie becomes involved with Honoré, gets caught up in his obsessive love and vision of her sometime after her husband Robert dies (and not as the result of a racial killing). Then, Honoré makes a mistake, a big mistake that she cannot readily forgive him for.

JT: It’s wonderful to have “A Movement in Eleven Days” back in print! Reading it I was reminded of Steve’s daybook collection of pieces “Skinny Trip to a Far Place.” I love the line “On the return of my poems because they were “almost too powerful for me….’” What was happening at the time in your life when this sequence was written? What called forth these poems?

GD: Well, I was being rejected for the umpteenth time by someone who I now wish, in hindsight, I’d never become involved with other than a rather distant friendship. But I wasn’t in the space then as I am now.

Fantasizing about sex and love was one thing, knowing what sex was like was yet another, wanting the kind of sex one could thrive upon and love was the missing piece. By the time I knew the subject of Movement, in Palo Alto, I was restless, and I was beyond just lust. I met him a couple of years after a young white bisexual man I had once loved had committed suicide.

I realize now that his death must have tripped another wire in me. It wasn’t just my guilt over Stephen’s death. I did not want to end up like him, rejected and without love. Rejection for me, though, was almost becoming routine. I felt that I had nothing left to lose. I had to try.

So I gave B a copy of what I was working on at the time when he returned from his research stint in Antarctica. I think that he was in shock. He had never figured what was really under my dark skin.

JT: Can you talk a little bit more about your time in the Women Writers Union? How did that shape your thinking as a young writer?

GD: It shaped me politically, I will say.

I could relate to the idea that art was inseparable from personal politics. However, I also had to revise my thinking about other women of color, and about lesbians and lesbians of color. I’m still revising and understanding.

I enjoyed the writing workshops very much, which occurred on Sundays each month, usually at someone’s home. I saw how the other women lived, whether they lived alone or with a male or female lover, or with friends, all of whom gave way to us. There weren’t always political posters on the walls, but there were books everywhere, just like at my home.

Sometimes the workshops were well-attended, other times not. But if you brought something, and yourself, you were heard. And to me, that was the most important thing. We also did readings at the Poetry Center, and at Intersection, and at bookstores around San Francisco. We organized a racism in the women’s movement event, and we marched on Gay Day.

Along with the “woman left behind” poems, I tried writing a series of vignettes based on being a clerical worker called the Mimi O’Graph Papers that I read while at Intersection. Eventually, I found that I didn’t like what I was writing, and it wasn’t as strong or mature, so I dropped them. I think “Customer Service” more than compensates for the Papers.

We were heading toward a more conservative time. This was the time after Prop. 13 had passed, and Prop. 6 or the Briggs Initiative was coming before the voters. It was before Milk was murdered and before AIDS ravaged the gay community. Unfortunately, women were leaving the Women Writers Union for one reason or another. I was sad about that. I was tempted to join Radical Women, whose members were a core of the union, but I wondered where that would take me writing-wise. I stopped writing; I couldn’t complete anything. I thought taking on more responsibilities in the union might spur me to write more.

There had been about three black women who were a part of the union, including myself, Luisah Teish, and another black woman whose name I can’t now recall, a librarian, who lived in Hunters Point. One by one, they left, and I felt like I was the “only one.” I felt that it was time for me to go.

JT: What was being a part of the group of New Narrative writers (largely male and white) like for you as a black woman from the South and a member of the WWU? I’m interested in your involvement in the WWU while you were involved in an “apprenticeship” with Steve Abbott and Bruce Boone in relation to your quote from the book’s afterword: “It’s trying to get beyond labels and ways of seeing and living. It’s a lot more complicated, like life” and then later “I didn’t want to be a black white girl any longer; that is, to extol every other literature except my own.”

GD: I had left the Women Writers Union by the time I was apprenticed with Bruce and Steve.

The fact is, I needed to get back in touch with my writing, and after attending some readings and doing my own homework about it, narrative writing seemed to be the way. Besides, I wanted to feel comfortable writing about interracial love. It was Bruce who said that I should try writing a novel, after it appeared that the poetry had dried up within me. That’s when I began the “family” saga that eventually turned into Sugar Wars. It was Bruce who suggested that I write a piece on black writing, and I picked the book, Our Nig, to expand upon beyond my review in the San Francisco Chronicle.

In the beginning, I knew that I hadn’t read much about my own people’s literary output. I started buying black poetry and novels, especially criticism about these same books. I don’t know how many books I read within a three-week period. I was like a computer loading up on data. That’s what I meant, that “I didn’t want to be a black white girl any longer.” I was now open to all forms of black writing, including the Black Arts Movement.

As far as having to relate to mostly white men, and white gay men in particular, you forget that I had had years of dealing with whites as teachers, friends, and lovers. I usually give people a chance before I begin to distrust them. I let them show me who they are. That didn’t mean that I would excuse any expression of racism or sexism in New Narrative, but that hardly ever occurred to me. I wasn’t uncomfortable with Bruce and Steve. I was interested in them as teachers and cultural comrades, and what they might impart to me. For the most part, they let me just be, and that’s what I needed. They introduced me to Frank O’Hara, In the Realm of the Senses, Jack Spicer, and the Noh Oratorio Society. Besides, I loved the gossip.

JT: Do you see your poetry and prose in dialogue? As a writer that works in multiple forms do you work simultaneously in different forms or do you find yourself writing in a single form at a time?

GD: With Sugar Wars, I’m Mattie’s amanuensis. It’s a kind of dialect that’s accessible for a modern reader. I want the reader to hear Mattie’s voice. When I write essays, and when I write poetry, it’s all different, like shifting gears. I wish that I could write in more than just free verse in poetry. Ekphrastic poetry: I’d like to try more of these.

JT: Your poems are often thoughtful character studies of both public figures (like Little Richard, Serena Williams, Elvis, Sarah Vaughan, poets like WS Merwin and artists like Wendy Yoshimura) as well as people your audience might not know (like “Doria the mother of the bride”). How do these particular characters enter your work?

GD: I’m touched by them. I have to be moved in order to write about them. Looking at Doria Ragland, the mother of Meghan, the Duchess of Sussex, sitting all alone in her pew, I was touched by her shining eyes, and her love in seeing her daughter very well married. I wanted to capture that moment.

I’m not a diehard fan of Little Richard or Elvis, but they permeated my childhood in New Orleans, like all the other early rock and rollers. I know more about both of them; I can muse about what and who they were and what they have become.

JT: I think a lot about the importance of storytelling and how New Narrative centered storytelling as a primary function whereby marginalized people can broaden perspective. A way to combat “straight white male gaze” as being a perceptual default for a lot of readers. What stories do you think we should be listening to right now?

GD: There are a lot of good stories and novels coming out of African literature these days. African post-colonial literature is not just about throwing off the yoke of the white colonizers. It’s the struggle of trying to fashion a self and an environment conducive to living as full human beings beyond nationality, or clan, or region–or beyond gender and prescribed roles.

And I’m also interested in Africanfuturism (as Nnedi Okorafor calls it), or African science fiction. This is how African writers–as well as black writers–are imagining themselves into the future.

I don’t think that either of these movements counter each other. If anything, they complement each other. They use myth, they use oral tradition, they use history to make it work.

JT: In the afterword to the book you write: “When I was a little girl, I declared that I wanted to remember everything.” In this difficult moment where memory feels like both a blessing and a curse, do you still wish you could?

GD: It was very difficult to call up the past—both my shortcomings and my triumphs—for this interview. Some memories, I think, are worth savoring. I still wish that I could remember everything just so that I’m reassured how much I’ve grown and changed.

JT: What are you currently working on?

GD: After my assignment with this remote temp job, I will be working on completing Sugar Wars. After that, I want to work on a retelling of Rebecca. But one thing at a time.