For Capitalism is the Sophisticated and Materialized Form of the Hatred of Man and of his Body. -François Guéry and Didier Deleule

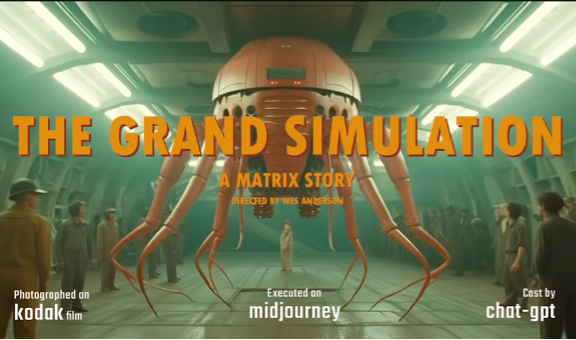

In 2023, the trend “Films if they were directed by Wes Anderson” began to gain popularity on TikTok. It broadly revolved around taking blockbuster films such as The Matrix (see cover image) or Star Wars and generating a number of images, clips, casting choices, and scripts, which ostensibly showed what these films would look like if they had been directed by Wes Anderson. All of these videos were created using generative Artificial Intelligence (hereafter referred to as AI) such as Midjourney and ChatGPT and were presented as fun gimmicks and experimental what-ifs.

At the time of writing, the use of AI-generated images has crossed from fan-made clips on TikTok boosted by smaller online proponents of the technology to large-scale productions. For example, a number of contemporary television shows and films have featured AI-generated images in their opening credits (Marvel’s Secret Invasion [2023]), in their intertitles (Late Night with the Devil [2023]), and in their advertising (Chestnut vs. Kobayashi [2024]). In a June 2024 interview with Google CEO Eric Schmidt at the Berggruen Salon, actor Ashton Kutcher stated that generative AI would soon dispense with a number of core crew roles in filmmaking. He waxed lyrical about no longer having to shoot real establishing shots, and noted that for a scene in which a character had to jump off a roof, “you [won’t] have to have a stunt person go do it, you could just go do it [with AI]).” He also argued:

you’ll be able to render a whole movie. You’ll just come up with an idea for a movie, then it will write the script, then you’ll input the script into the video generator, and it will generate the movie. Instead of watching some movie that somebody else came up with, I can just generate and then watch my own movie.

Kutcher’s ghoulish pronouncements not only obfuscate and belittle art and creative labor but also point to one of the central concerns of The Productive Body, an overlooked 1972 text by French Marxist scholars Didier Deleule and François Guéry. I argue that their work can provide us with useful theoretical material for an understanding of capitalism’s new favorite gimmick: generative AI.

In The Productive Body, Deleule and Guéry posit that the productive body’s entrenchment and subsequent dismembering leads to hyper individualization (“I can generate and then watch a movie on my own”) and the intensification of the disposability of workers (“you [won’t] have to have a stunt person go do it, you could just go do it [with AI]”). This dismembering of the productive body is one of the factors that leads to the rise of AI art as a labor-saving device. I argue that in order to better understand this development we must first look at the emergence of the productive body, as theorized by Deleule, Guéry, and Marx, as something to be known, controlled, and used to generate surplus value. The management and manipulation of the productive body is a development which Guéry sees as a result of the prominence of Cartesian dualism. This privileging of the mental in a hierarchy of labor is what allows for the subsequent dismembering of the productive body as I discuss below. The use of AI in the arts is not only a labor-saving device or a matter of mental labor and knowledge economies but is intrinsically related to these developments. It is through Deleule and Guéry that we can begin to understand the centrality of the productive body, and its dismemberment by neoliberal capital, to the rise of AI in the arts.

The Productive Body

In the first volume of Capital Marx begins to think about the bodies of workers as capital, particularly in the fourth part of the book. He tells us

the workers are isolated. They enter into relations with the capitalist, but not with each other. On entering into the labour process they are incorporated into capital. As co-operators, as members of a working organism, they merely form a particular mode of existence of capital. Hence, the productive power developed by the worker socially is the productive power of capital. (451)

While he does not use them systemically, the productive body or the productive organism are terms deployed by Marx in these chapters to “describe the collective organisation of labour-power as it is brought under the control of capital…the need for increasingly complex divisions of labour creates an opportunity for early capitalists to assert their control over production” (4). As such, The Productive Body is just as much a return to Marx, and a particular point of analysis which was left underdeveloped due to his death, as it is an updating. Deleule and Guéry begin their own book with this statement:

If all production requires means, and if instruments figure among these means, the production by men and women of their very means of survival seems to make their own bodies into the privileged instrument from which all developed technology, including machines, may be derived. All production is social, according to Marx, and thus the socialization of the body is one with its conversion into a means of production. (51, my emphasis)

The Productive Body’s translators, Phillip Barnard and Stephen Shapiro, note in a later chapter that “the text’s basic claim builds on Marx’s notion that capital has progressed by instituting a particular kind of alienation, wherein productive knowledge is separated from workers, and claimed as originating from (managerial) capital” (203). In this way the body of the worker, once socialized and thus integrated into the means of production, is simply a tool, limb, or cog, willed into motion and controlled by the “head” or “brain” of capital. The body itself is instrumentalized only after it emerges as a something to be known, socialized, and controlled.

The Historical Emergence of the Body

While Didier Deleule has since passed away, François Guéry was able to provide reflections on their book in his chapter within the recent edited collection The Body Productive: Rethinking Capitalism, Work and the Body (2022). In it, he elucidates his goals in the original text. He says,

my basic goal was to demonstrate that rising relative surplus-value, the object of the critique of political economy, exacts a high price on a different valence, one that is neither economic nor political. By this, I mean that the human body’s anthropological status, thought to have been transhistorical, now undergoes a delayed metamorphosis with catastrophic consequences. (22)

The body, for Guéry, comes into being only with the emergence of exchange and capitalism. As Steffan Blayney, Joey Hornsby, and Savannah Whaley note,“Guéry and Deleule’s interest in ‘the body’ then is not as a biological given, nor as an essential grounding for human subjectivity, but as an object which emerges historically” (4). They go on to argue that capitalism not only makes bodies productive “but produces bodies, and knowledge about bodies, according to its own imperatives” (4). This stands in remarkable similarity to Klaus Theweleit’s argument in Male Fantasies Volume 1: Women, Floods, Bodies, History (1987) that “the discovery of America carried with it the discovery of the body” (308). The body emerges, or is produced, along with new relations of production. The colonial subjugation of the Americas and the subsequent construction of a slave labor-based mode of primitive accumulation produces knowledge about both the bodies of the subjugated and the bodies of the subjugators and in doing so brings into being the concept of “the productive body” itself. As Deleule and Guéry state, “the appearance of the market, of the regime of exchange, of mercantilism, leads to the crystallization of the productive body, renders it visible, gives it a face and an identity” (46). It can thus be argued that the subsequent developments in capitalism such as industrial labor, the social division of labor, the centralization of production, automation, the subsequent decentralization of production, the rise of neoliberalism, and so on, all stem from this discovery of the body and how to control it and make it productive. But, they argue, before the division of labor there was first the division of mind from body.

Mind/Body Dualism and the Division of Labor

The Cartesian split opens the way for the division of physical and mental labor—a bifurcated self rather than a whole social self. Descartes’s famous formulation that the mind is separate from the body, in that it is non-material, led him to postulate the primacy of the mind. Existence extends from thought rather than being, summed up in the famous aphorism, “I think therefore I am.” As such, labor of the physical kind is denigrated. As Guéry puts it in The Body Productive, “the productive body relates to a peculiar separation of minds from bodies, associated with the mind-body dualism of Descartes, which has led to specialisations in psychology and a growing machinification of the body” (42). This becoming what he variously calls a “body-machine” and “living machine” throughout The Productive Body is to be put to use and “integrated into the functional processes of capital” (42). One key consequence of this, Deleule and Guéry argue, is that modern psychology develops away from the psychoanalytic method and becomes a way to “adapt the living machine to the dead one” (112); to proceed in such a manner that the living machine, in its ordinary functioning, becomes “as adapted as possible to the social mechanism into which it is in fact integrated, so that its productive act develops in optimal conditions and its gears don’t grind too loudly” (118).

This mind-body dualism that emphasizes the primacy of the mind also clears a path for the rise of managerial capital as controlling and directing physical labor itself. The “particular kind of alienation, wherein productive knowledge is separated from workers, and claimed as originating from (managerial) capital” (203) which I mention above is here made clear. Marx wrote about the separation of cognition from the working classes, and Philip Barnard and Stephen Shapiro rightly situate this as a core question in The Productive Body. They note that “tremendous effort was put into preventing the working class from having knowledge about how objects are made, in order to deny them survival skills that…might lessen their reliance on the commercial market for their goods” (213). The workers who make up the productive body are not only denied the full value of their labor power but also the knowledge of how to make the complete commodity which their labor power built.

François Guéry writes that “in The Productive Body, following Marx, we sought in technology the root of a properly capitalist power of the head” (33). Deleule and Guéry see capital itself as “the head, the caput, and thus also that which commands and directs…there is a power of the head, a power that is exercised…on its internal and external organs…the true split is here, in denying that this head belongs to the body, in the way one part exerts command over the whole” (32). This, Guéry argues, can be further evidenced by the dissident surrealists who “rallied against the head” when they founded the journal Acéphale or “headless” (33). Guéry goes on to note that in the original text and in wider discussion at the time, he and Deleule began to think of the Chinese Cultural Revolution and the Khmer Rouge as two moments in which the desire to “decimate urban society and the intellectual bourgeoisie in the name of a ‘proletariat’ which was not industrialized” was in fact a “fantasy of a body without a head and against the head, a body that could auto-decapitate” (33). In the contemporary period this auto-decapitation has in many ways reversed as leaps in technology, automation, algorithmic prediction and generation have allowed the capitalist to make it seem as if they have jettisoned the body, leaving only a digital or technological head to command and direct disembodied limbs.

The Productive Body Today: Algorithmic Governmentality

In the contemporary period, many of the aspects of capital teased out and critiqued in The Productive Body have only intensified. Barnard and Shapiro state that in the original text,it is argued that the capitalists have “seized control over the ‘mysteries’ and knowledge of production in order to claim they are the ‘real’ workers who make profit, while presenting labourers as little more than pieces of inanimate material to be purchased and used up” (203). The final chapter of the edited collection The Body Productive by Barnard and Shapiro provides an update for a technological and digital era under which neoliberal capitalism has only intensified. They note that “against expectations that the financial shock of 2008 would make it plain to all that neoliberalism had run its course and was now a zombie concept waiting to be abandoned in favour of something else, and much to the amazement of many academic commentators, the post-2008–11 phase instead accelerated and amplified neoliberal policies” (211). This analysis echoes Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval’s assessment of neoliberalism as radicalizing itself in the wake of the 2008 financial crash (15).

The infiltration of social networks into the everyday lives of workers and the creation of more “intense forms of precarious labour” (211) such as Uber, Deliveroo, and Lyft have simultaneously enlarged the productive body while fragmenting and decentralizing it. At one time, in order for the productive body to produce surplus-value it required centralization of workers in a factory or the office. Now, in an era of work-from-home, digital nomads, temp work, zero-hour contracts, and automation, the productive body is more spread out. Through this, laborers “experience class exploitation, in the absence of wage exchange, since they must dedicate their time to waiting for the possibility of being formally exploited through waged work” (212). One way this body remains controlled, that is, docile/utile, is through what Barnard and Shapiro call “algorithmic governmentality.” They use the term “algorithm” not as a technical definition but instead to indicate “an apparatus (dispositif), a mode of regulation occurring through the implementation of dynamic, ‘big’ data within social life” (211). This has become abundantly clear with the rise of artificial intelligence in the realm of cultural production.

Contemporary artificial intelligences such as Midjourney and ChatGPT are used to generate facsimiles of art, writing, and cinema, and are only able to do so due to the labor time congealed within said art, writing, and cinema, from which it has peeled off an aesthetic layer. Barnard and Shapiro argue that all forms of “collective, human achievement…become degraded as they are turned into a productive body, one that labours insentiently in the service of the endless accumulation of profit” (203). In the case of AI, not only is the labor dead and degraded; it is made “uncanny.” The uncanny, using the Freudian definition, is “the class of terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once familiar” (218). The products made by AI are all uncanny due to their familiarity. I argue that this familiarity is not just a recognizable authorial aesthetic but is in fact a recognition of congealed labor time. A feature length film requires significant amounts of labor time provided by the productive body of a film cast and crew. In AI generated media the congealed labor time of the productive body becomes spectral, digital, and detached from living labor. It truly becomes dead labor that lives the more living labor it sucks (342).

Artificial Intelligence as the Head without a Body

It is worth now returning to the “films if they were directed by Wes Anderson” TikTok trend. The films from which AI copied a certain recognizable aesthetic are not just Anderson’s films, they are products of myriad labor. The labor power of technicians, grips, VFX artists, actors, directors, editors, and so on, is bought for a wage and the finished product is released, distributed, and the profits reaped by studio owners and executives. The film crew, operating under a strict social division of labor, are the perfect example of the productive body in action, laboring intensely in one specific department in the service of the finished film-commodity and the subsequent accumulation of profit. As I note above, the capitalist has seized control over the mysteries of production in order to claim they are the real workers who make profit. This is akin to the “studio auteur” such as Marvel’s Kevin Feige or the Russo brothers, who are presented (by both Marvel and themselves) as the sole creative force driving profits and success. In this process the productive body is made up of laborers whose skill is both obfuscated and appropriated and the film becomes a product with a single capitalist producer.

Deleule and Guéry very presciently see that as workers become easier to hire and fire, they are increasingly compelled to compete against one another and to consent to work for less money. “This competition,” they write, “makes it seem to workers that they do not belong to a class or ‘social body,’ but must rely on their individual self or ‘biological body.’ These structural forces lead workers to begin to see themselves in terms of individual rather than group interests and demands” (21). In the contemporary moment it is not only cultural workers and artists competing against each other after internalizing the individualizing logic of the productive body. Now individual artists, parts of a dismembered productive body, compete against the repository of dead labor held by capital. As AI companies emphasize the ability to generate immediate art with boundless possibility, they conform to Deleule and Guéry’s assessment of capital presenting itself as a head that is responsible for all production of surplus value. With AI, capital is the head who, having escaped auto-decapitation, no longer sees the whole productive body as integral to the generation of surplus value. In fact, the capitalist head has realized that it can generate relative surplus value simply by chopping off some of its own limbs.

This is the ultimate goal for the contemporary productive body. Supposedly ephemeral, with the physical workers themselves obscured (eventually disposed of or made redundant), the AI film is, for the capitalist, the body removed from the head. Rather than the “auto-decapitation” which Guéry discusses in relation to rural proletarian revolutions, these attempts at AI art creation desire to do away with the troublesome requirement of labor power for the generation of ever rising relative surplus-value. The proponents of this mode, like Ashton Kutcher, argue that in the future all art will be made this way. (Such despicable and deleterious pronouncements intensified in the wake of the Writer’s Guild of America strike and the shutting down of a number of film and television productions in 2023.) What is unrecognized by Kutcher and his promotion of the head-without-a-body that is AI art, is that these generated images and video clips are only possible due to the massive amount of congealed labor time in the products with which the software is trained. This fact is ignored, and ignoring it allows such AI-generations to be presented as the new frontier of art. It is in tackling such developments that seek to further dispossess and oppress the workers that The Productive Body remains so relevant. To quote Barnard and Shapiro, “we may look to Guéry and Deleule’s study as a set of tools for rebuilding a new cultural materialism, a new historical materialism and a new Marx for the conditions of combined and uneven development we face today” (213). A new cultural and historical materialism that does not place itself in opposition to concerns of the biopolitical and governmentality. A twenty-first century Marxism to combat the new gimmicks of capitalism and the neoliberalized productive body.

Cover image: One popular AI-generated trailer for The Matrix if it were directed by Wes Anderson. Note the crediting of AI technology and, falsely, Kodak film.