1.

On the day I won a university award named after Rosa Parks, I learned that a student was weighing an invitation from Tucker Carlson Tonight to discuss an article he wrote that condemned my course on American political thought. The course does not explore iconic American political theorists or even anything by white men. It engages authors such as Audre Lorde and Gloria Anzaldúa—key thinkers of American political life in numerous fields but not in my disciplinary home, political science. These “deformations of American political thought”—to borrow the words of Michael J. Shapiro—were intended to raise critical questions: what is “American political thought,” why, and what is left aside? Although the student dropped the course after the first day, he reappeared with his smear piece nearly two years later. The story spread like a game of telephone through far-right outlets such as Breitbart. Harassment, racist messages, and death threats ensued.

Many people took this as a sign of conservatives run amok, emboldened by Donald Trump. That characterization works only to an extent. Student evaluations and comments on the article reveal that my class is disapproved of by liberals too. They declare support for diverse content but are aghast at the absence of Euro-American men.

At the heart of the article and its publics is a defense of whiteness. To support my case, here’s a shocker: the author is not white. Postracial folk of all political stripes read this kind of factoid as proof that something isn’t about race. Yet, whiteness thrives by weaponizing people of color against each other. It offers steep terms that are mistaken for a bargain: a taste of recognition in exchange for being a tool. Only a cruel optimist could believe that this ultimatum allows one to finally becoming human.

2.

I teach in Denver, which prides itself on being a blue rock in a red sea but has a narrow understanding of whiteness. My campus was built through the displacement of a poor Latinx community. That history is folded into other sordid ones: the dispossession and slaughter of Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Ute peoples; the razing by angry whites of every residence and business in a Chinatown that has never returned; and the terror of the Ku Klux Klan under the watch of one of its members, Denver Mayor Benjamin Stapleton. These legacies of whiteness are being intensified by rapid gentrification.

White liberals seem largely oblivious or indifferent. Many depict racism to be an issue of conservatives, dodging responsibility for the forms of whiteness they benefit from and leverage. Many ignore and belittle people of color while posturing themselves as allies. There is nothing new or surprising about any of this.

Meanwhile, whiteness gains new life by commandeering institutional diversity and inclusion policies from the people they were meant to protect. My university categorizes political affiliation and veteran status alongside race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation. When sociopolitical histories are displaced by identity matters, “diversity and inclusion” enables white folk to play the victim card. Conservative groups know this very well. They stretch the meaning of free speech to defend nefarious aims while sapping precious university funds to host and protect trolls and their un-rigorous, unfounded, and—let’s be real—racist, sexist, homophobic, and colonialist diatribes. When diversity and inclusion expand whiteness, where might minoritarian peoples turn?

3.

In The Difference Aesthetics Makes, Kandice Chuh argues that mere defenses of the humanities tend to support liberalist presumptions about the human that are overdetermined by whiteness. She calls for the humanities to be reconfigured apart from liberalism and its grounding in colonialism, antiblackness, and capitalism.

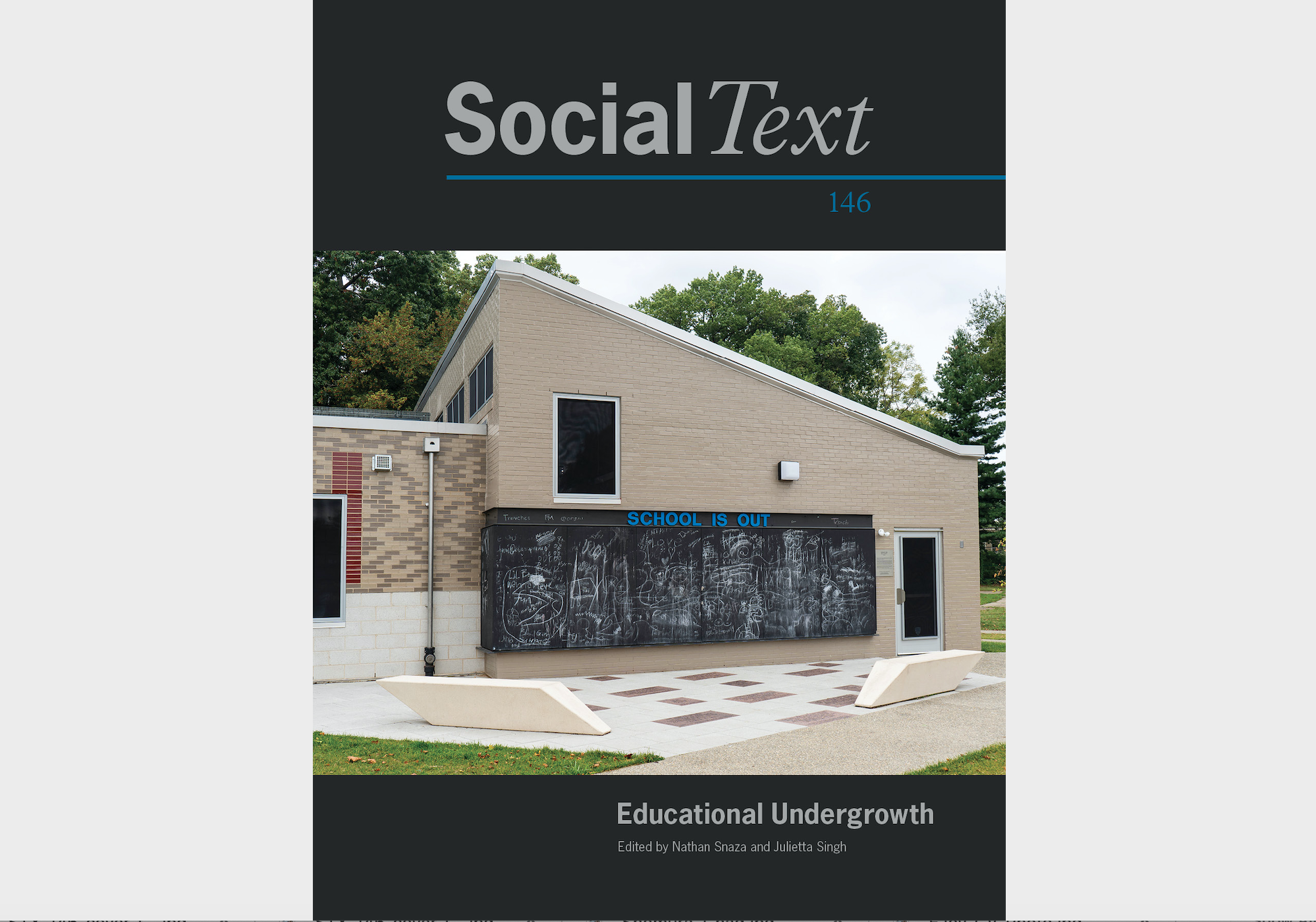

Julietta Singh and Nathan Snaza have also pursued these wayward paths. The issue of Social Text that accompanies this essay, “Educational Undergrowth,” provokes consideration of the university as a kind of ecosystem. How does the university become a manicured garden? Is it a plantation space? Is disciplinarity a kind of monocropping that clears away diversity, fosters only what’s profitable, and leaves the land barren in turn? What might grow in the ruins? What if the university were overrun with weeds? Would it become hospitable to forms of the human and knowledge undefined by whiteness?

4.

A student-led group of weeds known as “The Collective” has taken root on my campus. Its composition is Black, Latinx, Native, white, queer, femme, gender nonbinary, and neurodiverse. It is striving “to be in but not of” the university. When the campus hosted an inaugural masculinities symposium entitled “The Need for Men,” we decided that protesting would be a drag. (The event started at 8:00 a.m.). Instead, we threw a SCUM Party. It did not provoke the violent rampage feared by the Need for Men folk, though there was lively discussion of Valerie Solanas over snacks and music. Later, the students successfully pushed the political science department to generate an antiracism statement and land acknowledgment, fund antiracist initiatives, and offer courses on race designed and led by students of color. Last year, the Collective won the university’s Rosa Parks Award.

We are not satisfied with these minor gains. Our desires will always be unfulfilled because we want so much. And so, we accede to outrage, alienation, and burnout while under constant threat from all angles: from the institution, from conservatives and liberals alike, from faculty, from students, from all who defend whiteness. All this, for what? Nothing less than a world that can hold us. We deserve no less. Despite our best efforts, however, that world may never come.

0.

If that story ends in a downer, here’s another beginning: before the garden, there were the weeds. Their snarling masses defied apprehension. They always had each other. It wasn’t enough but it was all they needed. The weeds sprawled in every direction and thus always led to utopia.

José Muñoz showed us that utopia is not the pristine place it is often imagined to be. It is the impossible refuge of all who have been left without one: the perverse, the backwards, the abject. It can never arrive, and so it is always already here. Bored with the staleness of diversity and inclusion, the denizens of utopia are animated by unrest, agitation, and wildness. They turn humans into weeds, differently and evermore.

My grandmother once told me that weeds choke other plants, and I like that. Weeds are wildly creative, but they’re also threatening. No one has a clear image of the weeds. Their utopian power may be spied in every crack in the university’s ground and walls. The encroachment of weeds may be staved off by the most dedicated gardeners, but only temporarily. A garden is not an achievement but an exhausting, ceaseless endeavor. A little lapse, and that’s that. You’d better believe we’re always watching.