Housed in the former Supreme Court and City Hall buildings, Singapore’s National Gallery opened in 2015 under state sponsorship and is emblematic of the island nation’s ambitions to be a globalized Asian hub of not just shipping and finance, but also fine arts and elite culture. As a comparatively young, yet hypermodern postcolonial city-state settled mostly—as the official narrative goes—by humble, working-class migrants from throughout Asia (particularly south coastal China, the Malay Archipelago, and southern India) with dreams of upward mobility, Singapore has—perhaps wrongly—never really garnered an international reputation as a center of cultural production, as it has rather drawn attention for emphasizing efficiency, utility, and “practical” ventures with quantifiable value to achieve an overall high standard of living. While the National Gallery aims to rectify such misguided perceptions of cultural deficit (particularly in its exhibits showcasing more experimental contemporary works by local artists that push the boundaries of Singaporean social norms and acceptable levels of propriety), its mission nonetheless represents an ambitious continuation of the official narrative, specifically its “Global Asia” strand. Here, Asia does not really signify an “Asian identity” but rather a Singaporean self as engineered from its composite neighboring and interacting cultures, while global marks the cosmopolitan, elite, multinational arena in which that self asserts a space and a voice. A critical aesthetics must question the presentism, triumphalism, and historical elisions of Global Asia in this autoethnographic impulse.

Because of its ambitiously broad curation and arrangement of modern and contemporary paintings, calligraphy scrolls, sculptures, and interactive installations of variant Asian origins, the Gallery offers an ideal space to test out a critical aesthetics that questions the autoethnographic impulse of Global Asia: the Gallery architecturalizes some of the theoretical provocations of “Global Asia” as a concept, which the organizers of our symposium understood as conveying both “the interconnectedness of Asia and the world” and “Asia as a heterogeneous cultural imaginary.” A visitor’s individual itinerary through the museum encourages reflection upon the significance and symbolism of the arrangement of the artworks and whatever historical connections, commonalities, or divergences their spatial juxtaposition might convey. To this viewer, the colorful Southeast Asian paintings—ranging from Philippine artist Anita Magsaysay-Ho’s egg tempera on board, In the Marketplace (1955), to Vietnamese artist Nguyen Gia Tri’s lacquer on wood paneling, The Fairies (1933), and Burmese artist Bagyi Aung Soe’s oil on plywood, Self-Portrait (1986)—were captivatingly noteworthy in their own right, precisely because they invoked very different sets of formal aesthetics, as well as different sociohistorical contexts, perspectives, and concerns.

Rather than taking for granted the logic or seeming naturalness of the architectural arrangement and geographical divisions of the exhibited works, it is worthwhile to seriously consider how the diversity of artworks are arranged and exhibited to mobilize, prioritize, and ultimately project a global aesthetics of Asia nonetheless specific to the location, history, and experience of Singapore as a postcolonial nation-state of multicultural “Asian” immigrant foundations. For Singapore, the contested concepts of Asianness or Asianism (codified by an identitarian rhetoric of multiracialism and Asian values, as well as an emphasis on English-plus-mother tongue compulsory education) may be more vital to its national image than to other countries in the region (for whom Asia might signify divergent cultural or geographical attributes), since Singaporean-as-nationality does not align with a particular majority ethnicity or language, but is instead propagated as a site of cohabitation that inflects or accents the various Asian ethnic and linguistic divisions of its citizenry. The National Gallery can therefore be regarded as playing a constitutive role in Singapore’s ongoing self-fashioning of an Asianness/Asianism critical to its national image.

Approaching the National Gallery’s collection from the perspective of a critical aesthetics would presumably uncover narratives, visions, motifs, or snapshots of Asian interconnections that fail to conform to the professed aesthetic logic and official ambitions of the museum’s arrangement. A central question of our symposium included: “What aesthetics of globality have arisen in/out of Asia and what do/did they look like?” Here, the intentional addition of the past tense, did, is crucial, as it opens a space for the recuperation of historical aesthetics, imaginaries, movements, and alignments constitutive of the global, but in ways perhaps suppressed, obfuscated, or overshadowed by the currently dominant neoliberal discourses of globalization in a place like Singapore, in which Asianness and Asianism are mobilized to enforce consensus and compliance to the state’s vision of national development and civic participation.

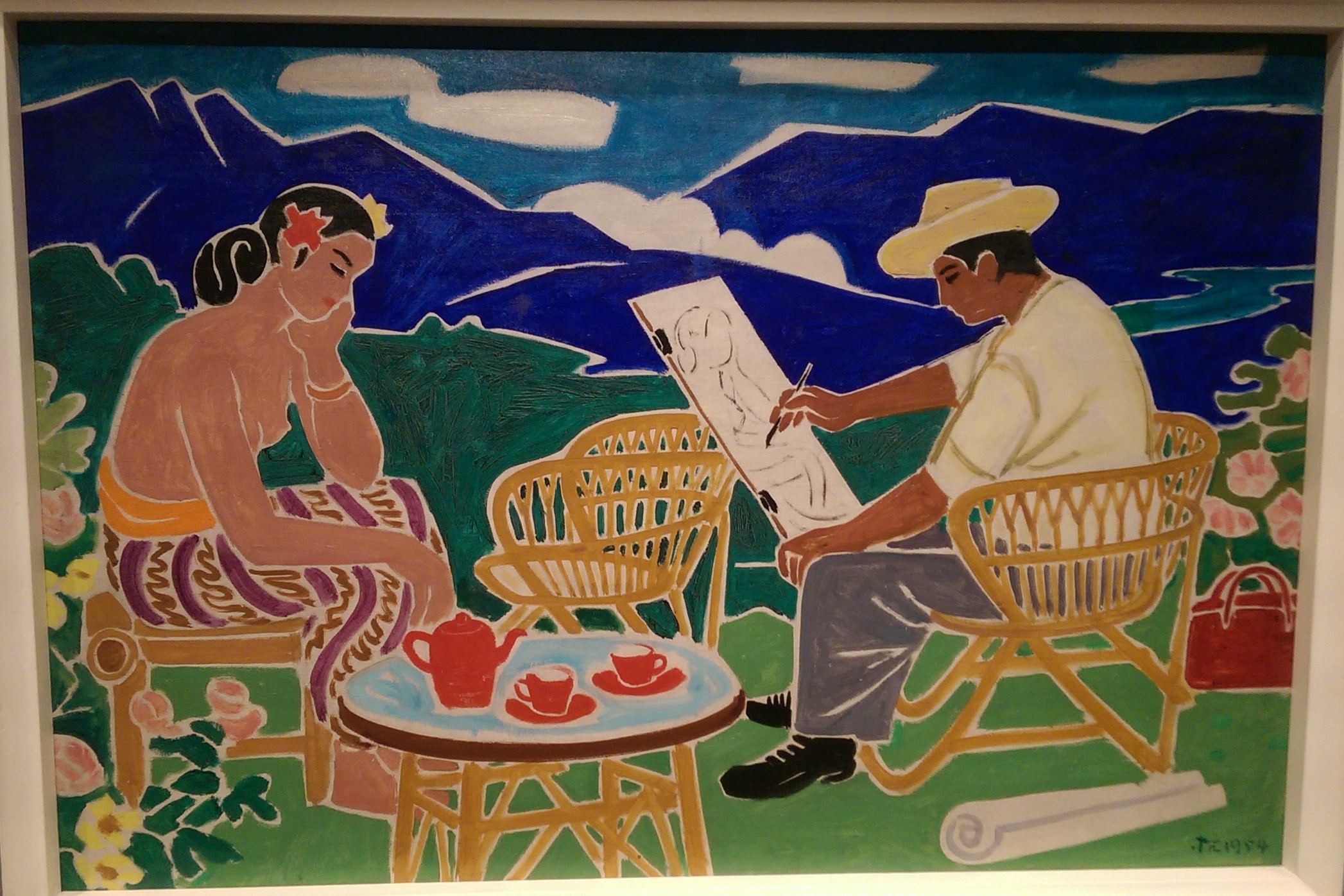

In the museum’s Southeast Asian gallery, Liu Kang’s Artist and Model (oil on canvas, 1954), pictured at the top of this essay, visually conjures a pertinent historical aesthetics of the global, one that reconciles with the complexly layered East/West and North/South inter-imperial dynamics of cross-cultural relations in colonial Southeast Asia. Gauguin-esque in its highly impressionistic rendering of the tropical South Seas, Liu’s painting depicts fellow male Singaporean artist Chen Wen Hsi sketching a topless female Balinese model against a verdant floral backdrop. Southeast Asia was known in Mandarin to Chinese travelers, migrants, and settlers in colonial Singapore like Liu and Chen (Liu was born in Fujian and Chen in Guangdong) as Nanyang, the South Seas, just as the Pacific Islands were to Paul Gaugin and other Western artists who traveled in the wake of maritime imperialism, seeking aesthetic inspiration in the colonies of the Global South. The artist’s appropriation of a Gauguin-like perspective toward his female model (and her tropical backdrop) raises the specter of the racialized and sexualized violence that facilitated the radically uneven encounter between the Western/Northern male artist and his Eastern/Southern muse. By meta-cognitively thrusting the male gaze and subjectivity of the Chinese composer into the painting itself, “Artist and Model” evokes modern Chinese fictional travelogues of the new cultural enlightenment in the early twentieth century.1For more on such fictional travelogues, see chapter 1 of my book, Writing the South Seas: Imagining the Nanyang in Chinese and Southeast Asian Postcolonial Literature. Similarly impressionistic in their sensorial effect, these literary narratives by major writers of the 1920s and 1930s such as Xu Zhimo, Xu Dishan, and Ai Wu likewise use the inspiration of Western aesthetic training to turn the gaze of the modern Chinese intellectual toward other cultures to the south. The subjective position of the male narrator—or of the sketch artist in the painting—implores the reader/viewer to question how the rendering has been shaped by gendered and ethnicized relations of authorial representation.

Yet what is most striking about the painting is that Liu gave the male Chinese painter a darker skin complexion than his female Balinese model, thus injecting a diasporic positioning in Southeast Asia to inverse the “yellow-brown” coloration scheme that accompanied China’s adoption of racial Darwinist discourses in the late nineteenth century.[2.For more on these racialist discourses, see Emma Jinhua Teng, Eurasian: Mixed Identities in the United States, China, and Hong Kong, 1842-1943.] Such unanticipated gestures of inter-Asian critique, similarly deployed in the aforementioned Chinese literary narratives, are legacies of earlier aesthetics of globality—fraught as they were by coloniality—whose Asianness/Asianism might productively and appealingly unsettle the representational politics of their contemporary exhibition. In the case of the prevailing Singaporean model governing the National Gallery’s arrangement, a “critical aesthetics of global Asia” unsettles the identitarian impulse of Asianness/Asianism as necessarily an autoethnographic enterprise: rather than a sum total of artworks from different Asian countries exhibited alongside each other to create a sense of collective cultural self-representation, the critical aesthetics unveils the trajectories and dynamics of movement, encounter, and intersection between and beyond different cultures in the region that are collapsed under an Asianist rubric. Always particularizing the discursive production of Asianness to local desires and ambitions, the critical aesthetics becomes just as much an endeavor to locate and demarcate historical and contemporary relationships with the “Asian Other” as it is a project of imagining an “Asian Self.”