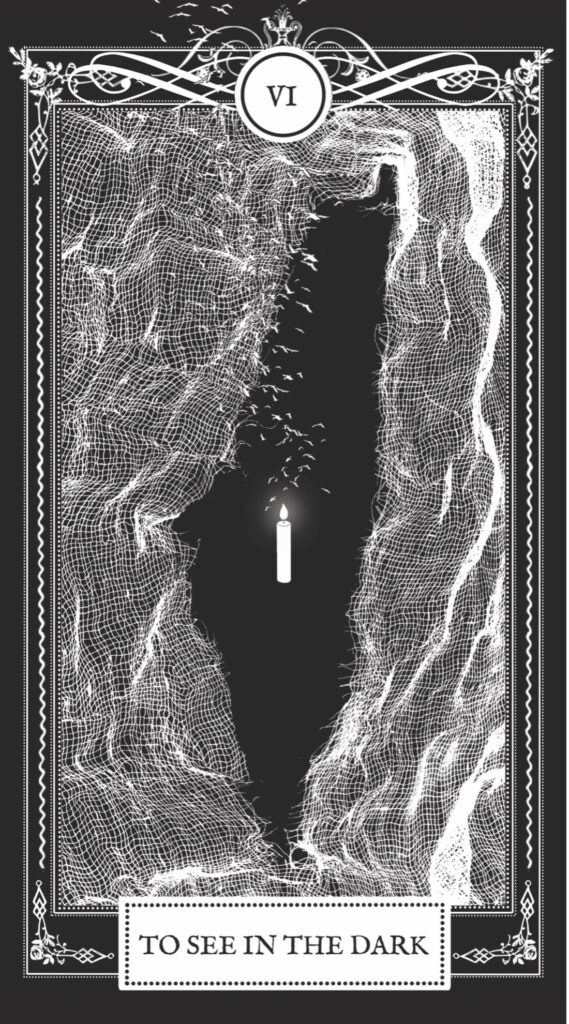

How to do things with being undone? How to forge solidary bonds in the dark of the rubble of a world destroyed but also the dark of a collective unconscious, a night, a space for sounding otherwise? To open Nicholas Mirzoeff’s book To See in the Dark: Palestine and Visual Activism Since October 7 is to encounter the image not as sign but, rather, as guide, portal, spell. A solitary candle lit with its flame in a field of black as if illuminating the way in the negative space of a Palestine and a Gaza torn from gauze bandages whose uncurtaining and frayed edges float and even flock as if becoming a murmuration, an anti-colonial pattern of the possible, a collective summons to seeing and flying together, navigating by the compass of each other’s presence in and through the dark (fig. 1).

Figure 1. To See in the Dark (Seven of Wands), designed by Amanda Priebe.

It is a redesigned tarot card that exerts its own magnetizing charge. A new version of the seven of wands designed by artist Amanda Priebe, it presents another way to spell out what has been rendered both unseeable and unsayable, casting a spell to guide our way through the prohibitive field of what defies sense. To pull the seven of wands is, according to Red Tarot: A Decolonial Guide to Divinatory Literacy, to be issued a poetic summons to creative revolt. The seven of wands after October 7th that opens To See in the Dark summons us into the solidary commons still here. As Mirzoeff writes, if the Gaza solidarity encampments were seeds planted in what I have described in “Doing Things with Being Undone” as a “landscape scene of genocide…restless, inhabited ground that makes us begin to sense what cannot be seen,” to pull this seven of wands is to be compelled to feel how these seeds planted in the dark may still and yet exert a gathering force (Mirzoeff 123).

After the calls for ceasefire, the UN resolutions, the global uprising, the encampments, it is tempting to re-ask activist Grace Lee Boggs’s question, “what time is it on the clock of the world?” And we might answer that it is time, more than time to see in the dark, to see not just from the rubble of colonial worlds and selves but also from what cannot and should not be unseen. To See in the Dark arrives as a solidary guide from the Jewish public intellectual, scholar, and visual activist who has persistently shown us—from The Right to Look and How to See the World to White Sight—how to strike, which is to say, how to show up for each other to turn the vulnerable situation of what Mirzoeff calls our “bare witness” into a revolutionary project of no less than remaking the world. To See in the Dark promises not just ways of seeing with the illuminating prism of Silvia Federici’s condensation that “Palestine is the world” but also ways of activating that seeing into a directional compass for another exodus, this time exiting the empire of genocidal violence and sexual abuse on generational repeat.

To See in the Dark joins the radical pamphlet tradition to offer us a how-to manual and stirring manifesto for the dispossessed, the diasporic, the targeted, and the refused, the outside of the inside in what to do with the ways that the political is also devastatingly personal. This is not merely a matter of the bareness of its own act of witnessing. It is especially the exposure of its turn to adumbrating an auto-theory of the intimacies of the colonial school of abuse as a primer in how not to perpetuate the violences that unmade us. To See in the Dark might also be understood as a companion in seeing Palestine outside the surveilling settler-colonial frame and its exterminating projections. This radical pamphlet is not just about solidary seeing but also arrives as a bolstering ally in finding our way to each other in and through our grief to sustain the global coalition for the free Palestine to come with the durational holding on of what John Berger termed our “undefeated despair.”

“We need not contain grief,” bell hooks taught us in All About Love. We might rather unleash its alchemy. With the condition, however, that when we use it, grief intensifies a practice of love that bonds us with the dead and dying that, loving into and across death, we grieve. After the Nakba (catastrophe) and in the face of the genocide in Gaza, what grief or love is enough in this necropolitical moment of calculated destruction of not just freedoms of speech and assembly, lives and life-worlds, but also what Ahmed Kabel names that “cidal swarm”—from ecocide and scholasticide to a vertiginous ontocide—that extends to our very capacities for sense-making attachment?

While the global uprising and campus encampments in solidarity with Palestine across the un-seen and refused of genocide and dispossession have called up a powerful us, that us is being riven by cynical weaponization of charges of antisemitism that enlist the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s (IHRA) working definition of antisemitism. The IHRA’s definition has become an apparatus of violence that is other and more than a tool for individually directed forms of censorship and weaponized grievance. As what Dylan Rodriguez characterizes as a “portable technology” for endless, asymmetric warfare or counter-insurgency, the IHRA definition abets the transformation of the surveillance and policing of everyday rhetoric from campuses to museums into a para-military theatre of investigation, criminalization, and carceral punishment.

At the center of this tactical destruction of the commons of sense is the way that the IHRA’s Zionist definition of antisemitism deploys its occupation of Holocaust remembrance to erase the tradition and living present of Jewish resistance to Zionism and force a “colonial unknowing” of the ongoing Nakba of genocide in Gaza. The increasingly normalized occupation of the work of memory and political imagination that steals our capacities compels us to reckon in the rubble and wreck not just with what lives are grievable or even who are our dead but with how to do the solidary care work of making apprehensible as actionable unrelenting, ongoing, and yet forcibly dissembled genocide and dispossession not to further divide but, rather, to summon and sustain the foreclosed assembly of proscribed solidarity with and care for a free Palestine.

To open a channel through the destructive thick of what Nasser Abourahme describes as “collective gaslighting” and its disavowals (“I know and yet…”) demands forging the proscribed bonds of what we might call a new universal, a proscribed transversal of solidary care—implied in the declaration that “Palestine is the world.” To ask not just how to see the genocide in Gaza, but rather, how to be with Palestine still engages us in the ethical and political work of not just contestation but also commitment to emergence—from the recognition and enactment of the right of return to abolition imagination and freedom dreaming (Casid). To ask how to be with a free Palestine still even as the bad-faith weaponization of accusations of antisemitism is used to undo us is not just a matter of living the questions. It is a matter of solidary care work at radically different scales that necessarily and urgently includes that of exercising the subjunctive power of our writing as scripts against proscription to make and shift sense by acting as if.

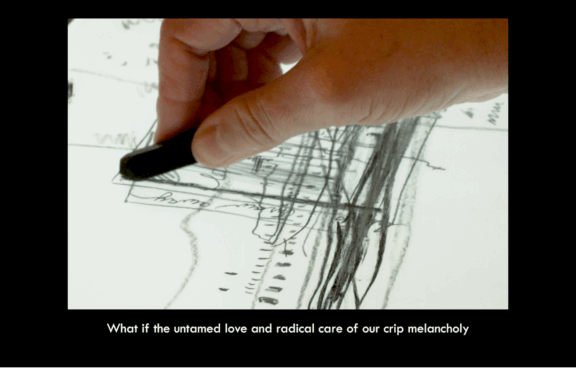

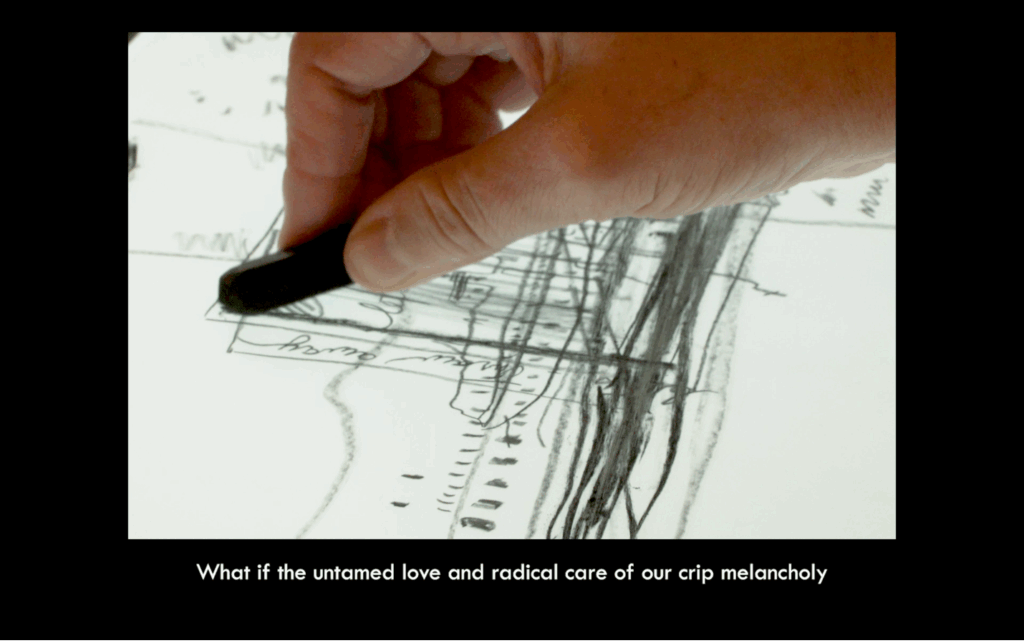

As the queer descendant of dispossessed Jews, many of whom did not survive, in my films, I have also recruited the strategies of autotheory to conduce an “I” who keeps company with the dead to refuse the tactical instrumentalization of Holocaust memory as fuel for the Israeli state’s genocidal war machine. To open the channel for a binding bond among the uncounted, this “I” issues its uncanny summons in the form of direct address as a kind of spell against proscription. My film Untitled (Throw Out) (2017-2022) (fig. 2) that builds on my published work in solidarity with Palestine develops the solidary care work of taking back melancholy, that pathologized other side of grief and mourning, to elaborate its potential as a medium for living our dying on a dying planet in ways that contest the terms of necropolitical abandonment that proscribe affiliation with the marked-for-death.

Figure 2. Jill Casid, Still from Untitled (Throw Out), conceived, written, and performed by Jill Casid and realized by Jack Kellogg, 2017-2022, Color video with sound, RT 16:30. Courtesy of the artist.

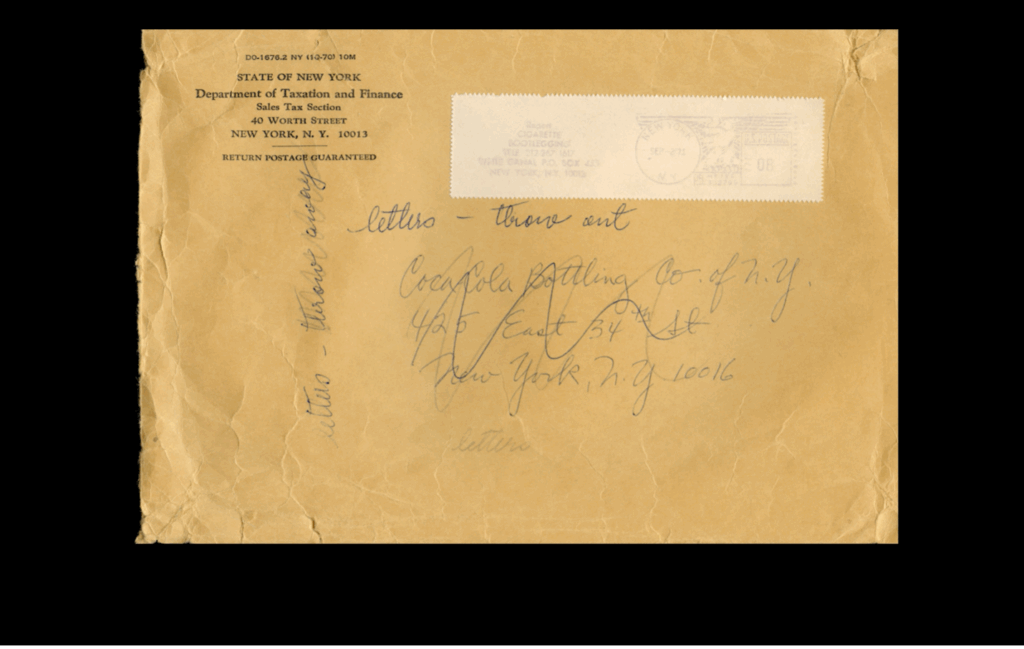

Untitled (Throw Out) (2017-2022) takes its title phrase and central animating vehicle from the handwritten instruction (“letters: throw out”) left by my great aunt on an envelope containing the incomplete remnants of an effort to save her mother who had been deported to the Gurs concentration camp in southern France (fig. 3). A densely layered palimpsest of image and sound, the film weaves unstable photographs with archival shards. My voice spells out while my increasingly smudged hand traces the envelope’s lettered surface and torn contents to call on the summoning force of spell-casting ritual. Following the envelope’s double-sided command to “throw out,” as in discard and “throw out,” as in to transmit, the film maps an approach from Gurs to Hart Island and its potter’s field as a way to draw the unmapped, even impermissible, connections across the throw-away world and the differential ways in which we are made to live our dying on a dying planet in a situation of killing disposability.

Figure 3. Jill Casid, Still from Untitled (Throw Out). Conceived, written, and performed by Jill Casid and realized by Jack Kellogg, 2017 – 2022, Color video with sound, RT 16:30. Courtesy of the Artist.

The throw of projection and visual and audio amplification of its instruction to throw out away confront to contest the conditions of being thrown by an activated melancholy that holds fast to and keeps company with the cast out in refusing to move on until there is justice and material reparation. Taking inspiration from the process of unfolding the charged contents of an envelope that bears the handwritten instruction to throw out and away and yet was, nonetheless, kept, the film pursues the envelope as praxis—as a way to push the envelope from enwrapping cover or limit toward the kind of care work that forges transversal connections of solidarity across the divisions of incommensurable but also disprized loss that might take us to the old sense of envelop—to be involved, to be wrapped together. The film takes us from the envelope to the letter and the other sense of spell to risk material speculation in the as-yet and the what-if—of being with a free Palestine still.

The wild, crip melancholy that the film practices as medium is not a mere synonym for the invocation of grief. Rather, as I develop this praxis, wild melancholy as medium names a structural relation to reparation and return that refuses to move on or let go of the matter of justice. Wild melancholy performed as a convoking summons—a call and response with the marked-for-dead—bonds an altered and altering us in a critical form of denied relation. That is, melancholy practiced in and as the wild may be a cry in the dark. But its howl reverberates to muster an unsanctioned, presumptively impossible us—a powerfully unnatural assembly with the uncounted and marked for dead beyond the divisions of nation, ethnos, kin, and kind. As a calling on and calling up, the summons of wild melancholy refuses the corrosive forces of unknowing that use the ruse of “safety” to suppress confronting the reality of settler colonialism and ethnic genocide by carrying our dead with us—Jews, Palestinians, Arab Jews, Palestinian Jews, Anti-Zionists, the unrecognized, the targeted, the marked for dead, and the otherwise refused—into the world not merely before but after Zionism to which it holds:

Risk material speculation in the as yet and what if. The what if we refused to stop mourning? Refused to move on? What if the untamed love and radical care of our crip melancholy—pathologized sign of a mad inability to move on—were our renewable energy source and untamed power? To summon a melancholy strike that refuses to accept the throw-away, let-die conditions of the anti-Palestinian, anti-Black, anti-crip, anti-Asian, anti-queer, anti-refugee, anti-femme, anti-trans necro-normal of settler coloniality and Apartheid. That goes with the throw to express being thrown. To transmit and amplify our not moving on as a material energy. The light-borne dust of the abjected and cast off. But not washed away. That returns as the promise and the risk of the intimacies of our contact.