We love our little objects. Perhaps you are reading this on yours, pinching and stroking the screen to enlarge the text. These physical interactions with the things themselves, with the actual media of media, are part of the history of reading, of looking at pictures, of listening to recordings. They embody the modern fantasy of portable culture, although to see our handling techniques solely as gestures of modernity is to ignore the distinctly corporeal pleasures we derive from our mediating objects. This pleasure can be difficult to describe, especially when it is obsolete. Try putting into words what it felt like to insert an audio cassette into a car stereo. I have devoted the morning to it, and all I have to show is a stilted fragment of nerdporn: “you feel some resistance going in, then the machine grips the tape and you hear a satisfying mechanical munch.” There is so much more to say.

If words fail to capture the sensory concreteness of past technologies, it is because the modern regime of obsolescence serializes our object choices and encourages us to forget past attachments. It is as if extinct formats and devices cease to exist once we have transferred our “content” to another “platform.” Reconnecting with the signifying properties of obsolete technologies requires unorthodox research methods, applied to archives we assemble ourselves from the sensory shapes of our own lives, from the “content delivery systems” of the past, and from journeys through technological subcultures populated with luddites, fetishists, and novelty collectors.

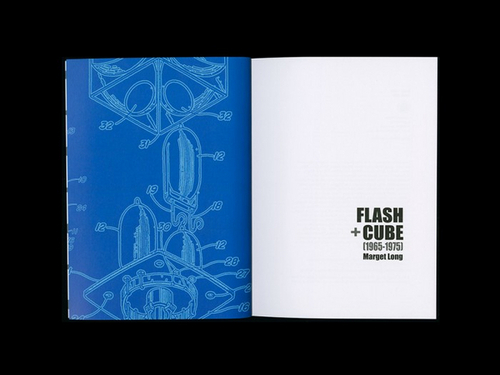

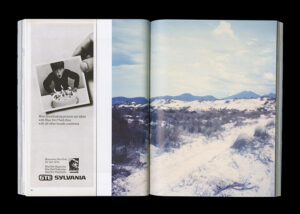

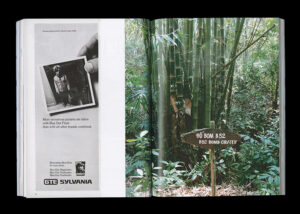

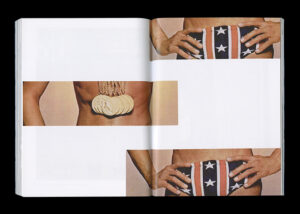

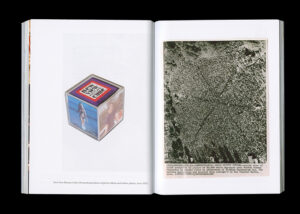

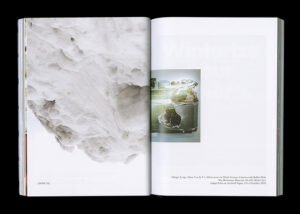

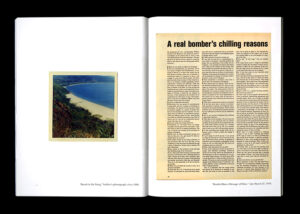

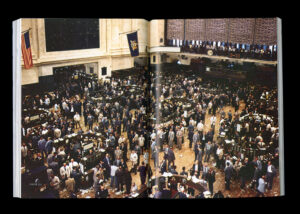

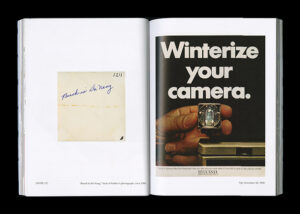

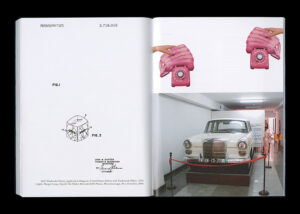

A recent artists book, Flash+Cube (1965-1975) by Marget Long (Punctum Books, 2012) exemplifies what such a project might look like. Its subject matter is a forgotten piece of technology, the Sylvania flash cube. Through an engrossing counterpoint of image and text, the book reconstructs relations of looking in the ten year period, 1965 to 1975, when flash cubes were marketed. As Long notes in her introduction, these were also the years of the Vietnam war, and one of the book’s achievements is the way it renders visible the often unexpected conjunctions between these parallel timelines. These conjunctions are formed in language and its tropes, in mentalities and visual repertoires, in bodies and their classification, and Long’s provocative stream of footnoted images conjures the diverse, crisis ridden contexts into which the flash cube entered.

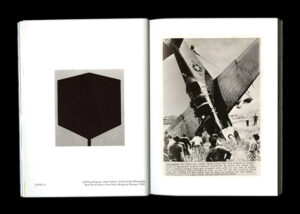

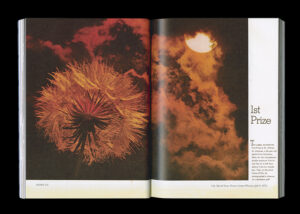

The techniques of assembly Long uses to create her image stream are not aligned with one particular discourse or disposition. A range of practices–montage, citation, repurposing, fan fiction, narrative testimony–go into her meticulous construction of an object’s sensory politics at a particular moment. Among the diverse source materials that comprise her archive are magazines advertisements, newspaper clippings, servicemen’s personal photographs, blog entries, and Long’s own work, including photographs she took in Vietnam in 2009.

One cannot communicate an object’s obsolete pleasures to others without specifying its place in the politics of sensation, past and present. This requires more than a deft verbal and visual rhetoric, although there is plenty of that in Flash+Cube. It also involves finding material and tactile modes of expression. Long finds them in the material form of the book. Flash+Cube is a page turner, by which I mean that my experience of reading it was highly physicalized. I paged forwards and backwards through it several times, fluttering the pages and scanning them with my eyes, clasping thick sections between thumb and forefinger as I compared, say, the front of a reproduced photograph with its reverse side, where someone had typed or handwritten a politically or personally revealing caption, and which appears later in the book. This is how Long choreographs the act of reading. Readers peer and riffle, marking and re-marking their places, as they peel ideas from her gluey archive.

Although its structure is non-linear, this does not mean that randomness governs the reader’s engagement with Flash+Cube. The book’s pages are carefully sequenced to produce particular reading sensations. Take a two page spread showing a sequence of stills from the film Hush, Hush Sweet Charlotte, “accompanied” in a footnote by a voiceover Long wrote herself. By themselves, the images wittily alert us to the paradoxical status of the flash in photography. It is at once an object and an event, it is both a source of illumination and an explosive and unpredictable element of the imaging process, one that threatens to eradicate the subject entirely. Reading back and forth between the still movie images and the text of Long’s voiceover creates new mental images–flashes–that personalize and embody the formal, epistemological paradoxes of flash photography.

Long encourages us to think about the apparatus of photography and the apparatus of history specifically through the act of grasping a book, but her oblique strategy can be applied to other objects–not only those that are obsolete (photographic prints, vinyl records, cassette tapes) but also those that have yet to become obsolete (physical interfaces, touchscreens, headsets.) From the oblique strategist’s perspective, it is not the platform that counts, but rather the cultivation of a sensory, physical experience in which, to (barely) paraphrase Ben Shahn, format is the very shape of content.

Today, “content” is a word that describes a new commodity form in the domain of cultural goods. It refers to those aspects of what we once called a work that can be considered alienable from it, and which constitute a new commodity form. It is new in that it has the power to create value (and diminish it) not only through traditional systems of exchange but also through its complex relation to the conceptual currencies of the digital economy: searchability, discoverability, interactivity, and so forth. In its “platform agnostic” form, the job of the content commodity is to undermine our outdated attachments, to make us fall out of love with our little objects as they grow older and bulkier, developing memory problems.

In her other work, Long uses photography, video, performance, and installation, alone or in combination, to explore the ineffable sensations and unspoken memories encoded in our physical relations with objects. An early series of photographs of hunting blinds in the woods of upstate New York is exemplary in this regard, and it strikes me that Flash+Cube‘s procession of concrete ephemera is a blueprint for a new kind of visual history, the kind that artists might be able to tell best.

Copies of Flash+Cube (1965-1975) are available at Dashwood Books.