The summer of 2014 was a crucial historical conjuncture in which Palestinian-Black solidarity both deepened and became more complex, as Angela Davis’s latest book, Freedom is a Constant Struggle (2015) was absolutely right to identify. The killings of Eric Garner, Ezell Ford, Kajieme Powell, John Crawford III, and, most significantly, Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri were immediately linked to Israel’s latest war on Gaza. Activists readily drew connections between Israeli racialized state violence in the name of security and U.S. racialized state executions —from drone strikes abroad and the killing of Black men, women, and transgender people at the hands of police—and the role Israeli companies and security forces have played in arming and training U.S. police departments. Palestinian activists were among the first to issue solidarity statements in support of the protests surrounding the killing of Eric Garner and Mike Brown. Over the course of the following year, young Black organizers from Ferguson as well as members of Black Lives Matter and the Dream Defenders in Florida joined delegations to the West Bank. Over 1,100 Black activists, artists, and scholars signed a “Black Solidarity Statement with Palestine” endorsing BDS. The statement describes Israel and its occupation as a system of apartheid based “on ethnic cleansing, land theft . . . the denial of Palestinian humanity and sovereignty,” and racism directed at Palestinians as well as African asylum seekers. The statement identifies U.S. aid to Israel and corporate investments in buttressing Israeli apartheid, singling out the massive private security firm G4S for its complicity in incarcerating “thousands of Palestinian political prisoners” and “hundreds of Black and brown youth held in its privatized juvenile prisons in the U.S.”

These acts of solidarity were given historical context by a veritable avalanche of recent scholarship documenting a much longer history linking the Black freedom movement in the U.S. with the struggle for Palestinian self-determination. Alex Lubin, Sohail Daulatzai, Keith Feldman, Hisham Adi, Theri Pickens, and Maytha Alhassen, among others, have substantially deepened our understanding of the emergence of modern Black-Arab political solidarity. Employing varying lenses of culture and politics, these writers’ texts reconstruct a history of what Lubin calls an “Afro-Arab” imaginary. This was made possible by several twentieth-century geopolitical shifts, for example, the rise of Pan-Africanism and Pan-Arabism in the context of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the creation of the League of Nations, the creation of the state of Israel, Malcolm X’s travels, the 1967 Arab-Israeli War and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s statement in solidarity with Palestine, the rise of the Israeli Black Panther Party, the global circulation of black music, the post-9/11 racialization of Islam, and relations of solidarity and tension between African Americans and Muslims from the Cold War to the present.

And yet, this recent wave of Black-Palestinian solidarity was quickly followed by charges of Palestinian or Arab anti-black racism that spread across the internet. The details and circumstances of these charges are varied and complex, and do not need elaboration here. I simply want to point out that the tensions generated some productive discussions, pushing many organizers to reassess their work. The many forums and debates, as well as the new historical scholarship, remind us that Black/Palestinian solidarity—like any solidarity—ought to be understood as a political project rather than some kind of natural alliance. There was never a time when the vast majority of Black people supported the right of Palestinians to self-determination or criticized Israeli policy, or when the vast majority of Palestinians—either in the Occupied Territories, in ’48 Palestine, or living in exile, actively supported Black liberation.

Solidarity is a political stance, not a racial imperative. Solidarities are often fragile, temporary, and always forged and sustained in struggle. Solidarity can produce internal fracturing within groups, sharp disagreements, and new alliances because it is constituted historically, in real places, times, and conditions. And no solidarity based on “identity” of any kind can achieve unanimity—that is to say, anti-Black racism does not produce a united, uniform, unanimous Black anti-racist response, nor do the depredations of Israeli settler colonialism produce a similarly unified Palestinian response. Internal differences of class, tactics, generation, location (geography), experience, and so on can generate ideological divisions, making solidarity among Palestinians and among Black people difficult enough. So we should not be surprised to discover Palestinian anti-Black racism, Black anti-Arab racism and Islamophobia, reluctance to build alliances between these communities, or what is often the most common response: indifference. To expect otherwise is to ignore historical context and political realities.

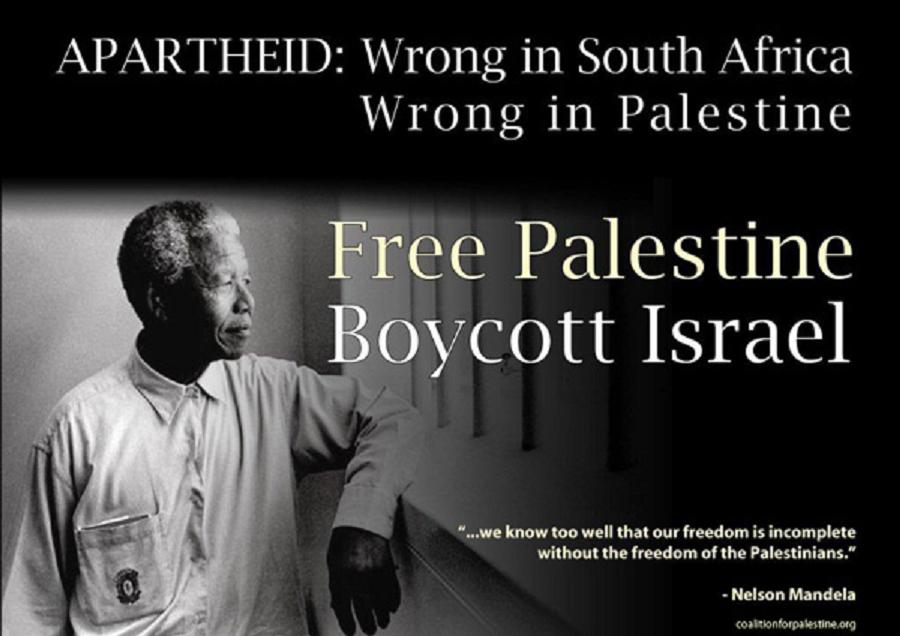

None of these internal challenges diminish the fact that BDS is fundamentally an anti-racist movement. Although its detractors continue to malign the movement with charges of anti-Semitism (and now, in some cases, anti-Blackness), BDS was always about winning freedom and racial justice for Palestinians. Indeed, by describing Israel’s subjugation of Palestinians as a form of “apartheid,” the BDS movement was not engaging in empty rhetoric or imposing an ill-conceived and inappropriate comparison with South Africa. Apartheid provided a language to interpret the racist character of the occupation and Israeli state policies; it strengthened arguments for BDS thanks to the success of the global anti-apartheid movement; and, most importantly, it exposed Israeli policies as direct violations of international law. The 1965 International Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), for example, declared apartheid a crime but based on a definition that was not limited to southern Africa. And the 1975 International Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid defines it as “inhuman acts committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them.”

Based on this definition, Israel has been practicing a form of apartheid since its inception. After destroying some 380 Palestinian villages and ethnically cleansing Palestinian towns and neighborhoods in mixed cities in 1948, confiscating land without compensation, Israel passed The Absentees’ Property Law (1950). The law effectively transferred all property owned or used by Palestinian refugees to the state, and then denied their right to return or reclaim their losses. The land grab continued after the 1967 war and military occupation of Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem. In violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention, Jewish settlements in the Occupied Territories have expanded exponentially since 1967. Most Palestinians in Israel are obliged to live in exclusively “Arab” villages that have been prohibited from expanding, attend severely underfunded schools, are denied government employment, and are prohibited from living with their spouse if she or he is a Palestinian from the Occupied Territories. They are routinely arrested for participating in protests critical of the state. Under the Likud Party, Israel has passed laws that directly infringe on the freedom of speech and academic freedom of Arab and Jewish citizens, including the so-called ‘boycott law,’ which allows citizens to file a civil suit against anyone in Israel who calls for a boycott against the state or Israeli settlers in the West Bank—whether or not any damages can be proved.

In the end, Black/Palestinian solidarity is based on the principle of resisting injustice everywhere and recognizing that the Zionist logic undergirding the founding and management of the state of Israel is based on racialization and colonial domination. Fighting anti-Black racism—and all forms of racism—is a basic principle of the BDS movement. As it grows in size, strength, and success, we should expect BDS to continue to be governed by a politics best summed up in Dr. Martin Luther King’s unforgettable line: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”