This short essay was commissioned by Dissent Magazine, which after putting me through an arduous editorial exchange rejected it. (Draw your own conclusions). I attach the original essay here, slightly revised and welcome any comments. I hope to expand it in a forthcoming book of essays.

How should the left think about race?

The prescriptive force of the question calls for certitude. My response is hesitation. There might be different, even incompatible ways to think about race. W.E.B. Du Bois described race as “the problem [that] cuts across and hinders the settlement of other problems.” It would behoove a politics defined as a systemic program of human emancipation — which is what I take to be the program of the left — to attain a fluency in understanding how varied operations of racial domination and its effects across the social field are understood and acted upon in the current period.

It is difficult in a brief reflection to illuminate all of these. But I start with these premises: 1) Race is a modern category that marks the (on-going) production of socially significant stigma against prevailing norms of human (species) universalism. 2) Race is a complex assemblage that links (what is thought to be) empirically observable, embodied difference to (what is thought to be) knowable deficiency of morality, capability and intelligence located in the ‘spiritual’ interior of individuals and groups. 3) Commonsense about what race is changes over time and across space; races are plural, heterogeneous and historically produced and are operationalized at different scales and across national borders. 4) The unchanging core and purpose of race is to naturalize social hierarchy. 5) Race is inseparable from the production of public threat and the periodic exercise of state sanctioned violence that responds to that threat.

Race, in short, is a modality of group domination and oppression. Yet, it requires a public story (whether biological, sociological, anthropological, or historical) explaining how and why such domination and oppression is justifiable and reasonable. A paradox faced in thinking about race today is that to be counted as a reasonable person within liberal society, one must accept the public account that rejects race as a legitimate mode of domination (even if private beliefs in race as a real ‘thing’ persist). Where racism is avowed, it is met with stigma and sanction. Historic indices of racial domination, including group differentiated vulnerabilities to violence, poverty, punishment and ill health, are in this view, thought to be vestigial, un-systematic and lacking in social authorship, even if their elimination is considered socially desirable. Deepening the paradox is that for liberal institutions, adding non-transformative racial diversification is surest proof of racisms vestigial character — up to and including electing a black President.

But along the way something happened. The seeming containment of race talk by a color-blind consensus dressed in trappings of diversity began to fall apart. Racist talk thought banished re-emerged with a vengeance. When it lamented a loss of country, and monkey-socialist-terrorists occupying the White House, it could be ridiculed as fringe. The visibility of torture, abuse, murder, mass deportation and imprisonment of black and brown men and women with extreme prejudice and public sanction, from Guantanamo, to Abu Ghraib and the mean streets of Chicago, Ferguson, New York and beyond, by police and military forces of the United States, has been less easy to disavow and disclaim. Meanwhile, the so-called housing crisis exposed how predatory capitalism continues to thrive upon market behaviors that presume and profit from unequal racial worth. In this context, the idea that the toxicity of race is consigned to the past is similar to the denial that humans have made the planet hotter and less habitable.

And, yet, a lot of ground was lost, particularly within a certain segment of the left, which in the aftermath of the civil rights era frequently partook of a mean-spirited universalism that viewed most race talk as a distraction from fundamental and more general inequalities of capitalist society. As the post-racial edifice collapses, we thus approach a new iteration of a familiar crossroads in how to think race and class together, and specifically how to pose the question of the relationship between anti-racist and anti-capitalist struggles in the United States and beyond.

Today left thinking about race must grapple with the claim that black life matters, and with the activist energies that are coalescing behind it. Though neither a singular movement nor fixed ideology, for many whose political action and commitment begins and ends here, the rampant police murder and hyper-incarceration of black men and women in the US, suggests that race — especially the anti-blackness that produces blackness — is a political ontology — whose durability after slavery and across several centuries has been retained as a distinctively modern form for enacting arbitrary and gratuitous violence within political orders otherwise defined by rational subjects of interest.

The contemporary left, by contrast, partakes of a mainstream, social constructionist view of race as fictive and foundation-less, though as a more oppositional version of the same, it categorically rejects race and class hierarchy in all forms. However sympathetic to anti-racist struggle, it remains difficult for left analysis and action to resist the political and theoretical reiteration of race’s secondariness. This stance retains traces of an older socialist presumption — that the race line is ‘merely’ a class-line in a different and deceptive guise — that any “left” politics that puts race first risks a descent into parochialism and mystification, leaving foundational issues of capitalist domination and class inequality untouched.

Those who insist upon race as political ontology and (pace Du Bois) on its universal effects across the social formation are not at odds with social constructivism. Most insist upon history rather than biology as the basis of racial blackness in some dimension. In the face of an overweening durability and continuity of an anti-black dispositif, however, they draw different conclusions about the primacy of race, its deleterious effects, and how to confront them. Many versions of ‘race-first’ argument and organization have existed at different times, and the left has partly claimed powerful radical proponents of these views, like Malcolm X, as its own. But differences remain stark between political understanding that emphasizes genealogies of social death, cruelty and ascribed human depreciation, and accounts premised upon the ubiquity of exploitable, abstract labor. This does not necessarily mean we must dis-embed race from the history of capitalism — but it surely complicates claims about universal distribution of suffering within that history.

Important attempts have been made to square this circle. In an oft-quoted line, the great, black British left intellectual Stuart Hall described “race as the modality in which class is lived, the medium in which class relations are experienced,” understood and fought over. For those who remain suspicious of leftist relegation, however, the effort rarely goes far enough. But the failure to scale up struggles, as Martin Luther King, Jr. noted, when he insisted “our fight is for more than the rights of Negroes,” is fatal — and the strict claim that ours is foremost and exclusively an anti-black world sometimes embraces fatality as fate.

No left worthy of its name can aspire to anything less than willful, even hopeful challenge to broad divisions of wealth and power that constitute and shape our society at a global scale. And yet, another kind of error and obliviousness is often admitted in its pursuit. For while it is possible to hold a common radical critique of all forms of racial essentialism, it is also possible to continue to diverge sharply about the meaning and purchase of race as a specific form of violence that is enacted differentially, and in a manner that (re)produces group differentiated distributions (along with different subjective perceptions and experiences) of vulnerability to police violence, criminal punishment, homelessness, joblessness, stress, illness, poverty, and loss of life.

A left that aims at broad social transformation cannot afford to attend to these differences with indifference, with dismissiveness, or even at a sympathetic distance. This is not only a question of strategy — how we should organize — but it is also a matter of recognizing how racial ordering, and the sexual and gendered violence that both accompanies and exceeds it, distorts common human experience and social relations in a manner that calls for wholesale ethical reconstruction in conjunction with struggles for political-economic restructuring. The trickiness of race is that it is a modality that enhances the viciousness of capitalism by aiding in the elaboration of its reduced human morality, and at the same time a category whose overcoming is now said to exemplify the possibility of achieving justice under capitalism. The latter sense of race mystifies capitalist injustice, even as the former helps to sharpen our sense of it.

In the US historical experience, black freedom struggles offer key insights into how radicalizing opposition to racial domination is a route to a universalist politics of human emancipation grounded in political economy. In the era before WWII, elite consensus viewed capitalist civilization as a racial and colonial project. Despite post-racial and post-colonial transition, it is not clear that capitalism suddenly stopped being what Cedric Robinson termed “racial capitalism.” From structural adjustment to subprime mortgages, the naturalization of the unequal worth of peoples has been retained as one of the surest ways to justify and profit from collectively enforced misery.

The black radical tradition that Robinson among others excavates is not much cited by some who speak from the left, and yet gleefully troll the most trivial and narcissistic idioms of racial politics to affirm their view that racial politics is an irreducibly bourgeois idiom. This approach serves to further alienate thinking about class from thinking about race, effectively conceding racial politics and reform to liberals and conservatives. In response, we should remind ourselves that black organizing and anti-racist activism was at the forefront of the most radical reform periods of U.S. history, including Reconstruction, the New Deal, and the Great Society, while from the early cold war to the Reagan revolution into the present day, overt and implicit racism has been the bedfellow of political reaction. Rather than deriding race-first politics as a mode of neo-liberal incorporation, it is healthier when the left actively supports and promotes, as black radicals from CLR James to Ella Baker counseled, independent black political initiative as the bellwether of broader radicalizations.

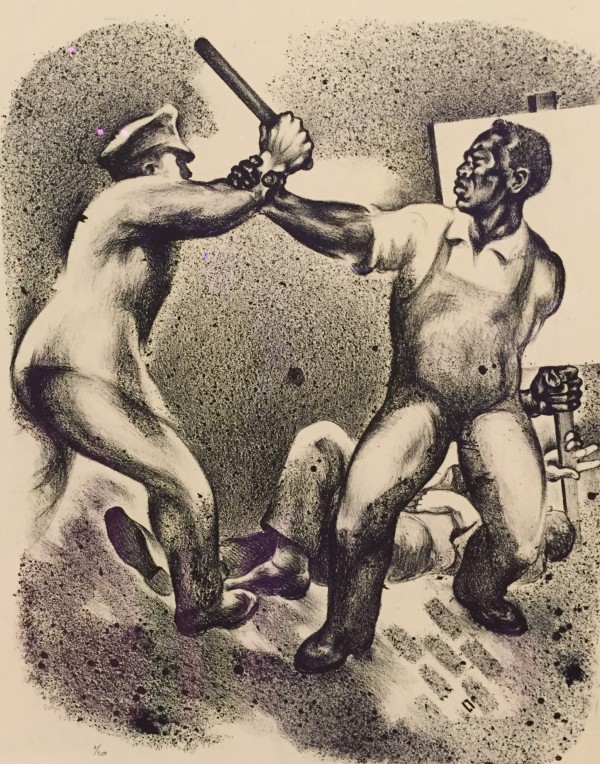

Photo Credit: Louis Lozowick, Strike Scene (1935). Lithograph. Sheet: 15 7/8 × 11 3/8 in.