Look at the world that was blind to us before and how it sees us now.

–Ibrahim Nasrallah, translated by Huda J. Fakhreddine, Palestinian: Four Poems

Here are some notes from the two days of Nicholas Mirzoeff’s Bay Area visit, late March this year when he appeared with Priscilla Wathington at Tamarack Free Library in Oakland on a Saturday afternoon and on Sunday evening with Omar Zahzah at Medicine for Nightmares in San Francisco’s Mission district, at each occasion with the Center for Convivial Research and Autonomy and others present. (Unmarked citations outside these notes are from Mirzoeff’s To See in the Dark.)

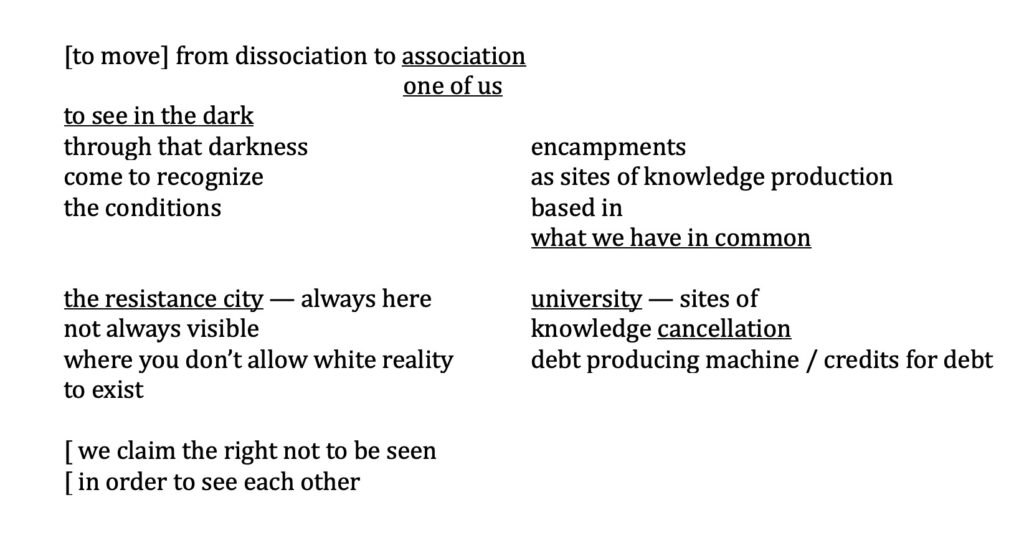

For the many of us who are being asked (and are moved) by Palestinians to see outside the frame of, the regime of white sight (“a colonial technology that creates a visible white reality”), outside its controlled image-constructs and interpretive entrapment, we join with those all around the planet “who [choose] to see people as people not data.” Not as legitimate or illegitimate “targets” or “terrorists.” Not as unfortunates, cast to fate. One has to be trained (cruelly) in coerced normativity as a good US-American-Euroamerican subject to accept as justifiable the surveillance data collected to spit out caloric intake charts and kill-lists: data that’s instrumental to what Denise Ferreira da Silva (with her astounding reading of Octavia Butler’s novel Kindred) helps us see as “this perverse circuitry that resolves the economic as the ethical” (13). As Mirzoeff insists, on repeat, in the pages of To See in the Dark, it’s “structure not event” that’s producing atrocity.

One of my tasks in support of the student encampment that rose up in support of Palestine in May 2024 at San Francisco State University was to fetch coffee in the mornings, provided gratis by Nabil, who I’d known from twenty years earlier when he worked for Ayman at another Palestinian cafe across the Bay in Berkeley. The food and coffee scheduling was set up by Federico, mathematician and musician, whose band with his partner May-Li and others, Neblinas del Pacífico, studies and practices Afro-Colombian music, a voices-and-marimba song form, marimba de chonta. At the time of the encampment Neblinas performed, after sets by three poets, at The Poetry Center which I was then directing at SF State. For one song we in the room were asked to sing the two-word chorus: dignidad, felicidad. These kinds of words, as we know, don’t work (being interdependent we can’t bring them to manifest as the condition we’re inside of) until they’re collectively sounded together and sustained across time-space and matter. And the place of that sustenance is a generalized “out-of-placelessness” that’s shared, collectively inhabited, proto- and pro-communal in its lived connectedness.

We see what’s going on when trusting what we have in common, and so as we move from dissociation to association. A few weeks after Mirzoeff’s visit, Fred Moten came through town. Near the end of his talk presented as the Hayden White Memorial Lecture at UC Santa Cruz, moved by Palestinian scholar Sophia Azeb speaking from the audience, Moten voiced this embrace of “out-of-placelessness.” Azeb asks, in an essay published at the same time as this talk: “How do we return to live the uninhabitable? The already stolen? The already destroyed? The already dead?” The place of assembly—as Azeb draws on Ruth Wilson Gilmore (who draws on Amílcar Cabral in her recognition of “making freedom by making place”)—for “the diasporan . . . compelled to constantly reimagine and renegotiate making freedom as they make place wherever they are,” can be seen, if we follow Moten’s re-sounding, as an activated time-space of “all-over-the-placelessness.”

In this “all-over-the-placelessness” we’re made aware, seeing that “[t]he dark is a place of sound and . . . ‘sounding,’” of how we are also always collectively hearing, listening together with them whose scattered names we come to know and re-know, whose words and work we’ll study, repeat, and reanimate. This peopled “all-over-the-placelessness” carries names, faces and voices—though also it’s where “we claim the right not to be seen in order to see each other.”

It’s a verb construction in the infinitive, “to see in the dark,” so an abiding form waiting ready to be activated (what friends with the Center for Convivial Research and Autonomy, after Ivan Illich, will identify as “a convivial tool”): “Dissociation passes via darkness into association. Once activated, seeing in the dark teaches ‘how to be in the negative and in the loss.’” And “[t]he dark’s material ground is rubble…. One eye sees through tears, the other attempts to take the measure of what is seen.”

When getting my copy in the mail and first reading Nicholas Mirzoeff’s book To See in the Dark, I opened its pages at their near-exact center and, caught up in the relation, read forward from there to the end and then back to start at the start. Isn’t what’s “most inside” said to be at the heart of a book? I am recalling here a line by Henry Corbin, French scholar of Sufi mysticism, in his great reading of Ibn ‘Arabī: “the heart creates by ‘causing to appear’ only that thing which already exists” (226). The presumed (by white sight) one who is seeing will have been “in the dark” more-than-one.

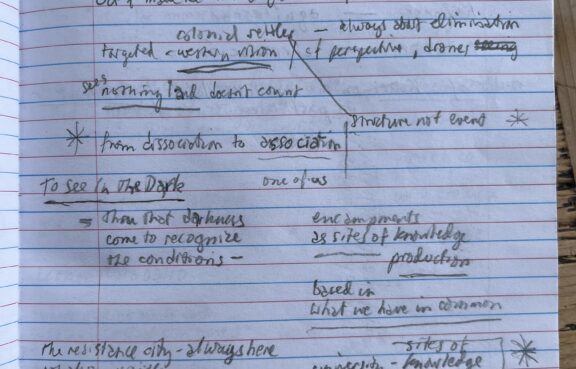

The page of poetry that follows starts with words spoken by Mirzoeff, as I wrote them down, this page a fragment from a work in fragments; from the second part, begun this May, of a manuscript I’d written the first part for this past November to February.