I would like to take this opportunity to contextualize Nicholas Mirzoeff’s To See in the Dark as part of VAGABONDS, the series of short, pamphlet-like books I edit for Pluto Press.

I founded VAGABONDS in 2020 based on three frustrations. The first was constantly getting snarky feedback in peer review that my work was “too polemical.” The second was that, even though arguably more words pass in front of human eyeballs each day than ever before, it seems that, in this digitally mediated age, fewer and fewer people are reading seriously. Third, the publishing industry is in crisis and has rarely seized the opportunities presented by digital media.

This all led me to propose a series, as we indicate on the website, of “long revolutionary essays and experimental works at the intersection of radical action, interventionist art, and critical inquiry” that would be “anti-colonial, queer, feminist, and militating for collective action and radical joy (including the joy of reading)” and that would be “too feisty for the academic press but too thoughtful for the online outrage machine.”

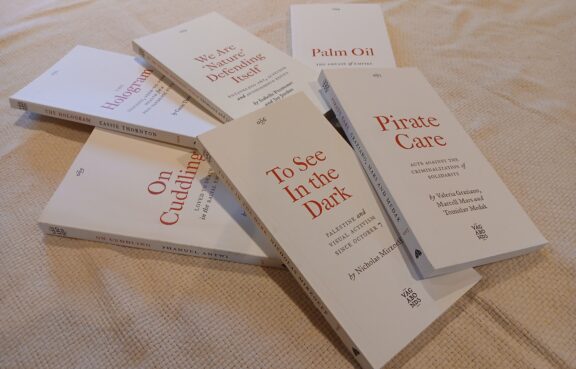

In 2020, the pandemic edition of the ongoing neocolonial class war prompted me to accelerate the VAGABONDS project. Thanks to a partnership with London’s venerable Pluto Press, renowned for five decades of rigorous radical books, we were able to speedily publish Angela Mitropoulos’s Pandemonium, a phenomenal critique of biopolitical capitalism in a time of plague, and Cassie Thornton’s The Hologram, a manual for constructing mutual aid cells that foreground mental, physical, and social health as key interlocked terrains of struggle.

These first books were joined by a third in 2022, We Are Nature Defending Itself (co-published with the Journal of Aesthetics and Protest), a memoir by key protagonists at the ZAD (Zone à Défendre) near Nantes in France, who came into new communion with the earth-of-which-we-are-a-part through a militant struggle against the building of an airport. In 2023, I contributed my book Palm Oil: The Grease of Empire to the series, an experiment in focusing on one capitalist commodity that is everywhere and nowhere as a means to tell a story about our world. In 2024, Phanuel Antwi’s groundbreaking On Cuddling: Loved to Death in the Racial Embrace combined poetry, theory, testimony, and imagery into a profound meditation on the terrifying violence that literally and figuratively crushes Black life.

And so when, in early 2025, we were able to publish Nicholas Mirzoeff’s To See in the Dark: Palestine and Visual Activism After October 7, the book found itself among radical friends. It was fortuitous that, in the same month, we were able to bring to the world Valeria Graziano, Marcell Mars, and Tomislav Medak’s book Pirate Care: Acts Against the Criminalization of Solidarity, a vital riposte to the somewhat tired recent “care turn” in radical letters, which shifts our focus to the protagonism of people and communities defying laws and breaking the rules to provide solidarity in moments when it is being criminalized.

I had already approached Nick in 2021 to sit on VAGABONDS’s editorial advisory board, a group who help me as general editor to seek out prospective titles, to vet proposals, and occasionally to act as reviewers in the open, dialogic process we devised to make the (often horrifying) process of peer review a meaningful opportunity for radical communion and committed intellectual collaboration. Nick came to me in 2024 with a fire burning in his brain to develop a book that would draw on and extend his pathbreaking work on the politics of the visual to make sense of the heart-destroying images we were all seeing as Israel’s Gaza genocide unfolded.

The idea was both phenomenal and fraught. Daily we were (and are) subjected to fresh visual evidence of unspeakable atrocities, images we cannot unsee, where the world’s most powerful weapons are unleashed on the bodies of people including children. In the midst of this livestreamed genocide, we are also witnessing the emergence of new and profound forms of visual activism within and beyond Gaza, new forms of media protagonism that insist: do not look away; do not (in Mirzoeff’s terms) dissociate, avoid and refuse to see the darkness for what it is; instead, associate, connect and learn to see the world anew in the darkness, without any false optimism or comfortable pieties, but with an eye to the long iron arc of empire and the longer but far more fragile arc of rebellion.

But the project was fraught too. Because what good is a book in a world where we have taught ourselves to tolerate…I won’t name the carnage. You’ve seen the images. We’ve all seen the images. We can’t unsee them. What’s the point of another book, another theory? And even if this book tells the truth about the massacres, and even if it tells the truth about the death dance of Zionism and imperialism, and even if it tells the truth about the heroism of journalists and image-makers on the front line (and even if it tells the truth about how the front line is everywhere now, as Palestine becomes the world and the world becomes Palestine)—what good is it when, in spite of all our sorrow and fury and protests and words, the genocide just continues?

And yet the book needed to be written. Many books need to be written.

As Nick and I discussed it, it became clear that this book would have to respond to many callings. First and foremost, the call to center critical Palestinian voices and highlight the steadfast protagonism and ongoing rebellion and refusal of the people of Gaza. Second, the book would need to be clearly articulated from Nick’s positionality as a Jewish man (a position we have in common), teaching at a prominent Western university, but also as the inheritor of a troubling relation with the state of Israel, and as a survivor of child abuse within that great crucible of imperialist subjectivity: the British elite school system. Finally, the book would need to be of service not only to scholars but also to artists and protagonists of the radical imagination, and most importantly to those organizing and putting their bodies on the line. Those readers must be able to find value in this book.

In all these tasks, Nick and I and To See in the Dark were very lucky to have excellent peer reviewers. We were also fortunate to have the assistance of Pluto commissioning editor David Shulman, who liaises with me about the VAGABONDS list. The book builds on Pluto’s singularly steadfast and courageous record of publishing many of the most relevant English-language books about the Palestinian struggle over the last fifty years and being perhaps the preeminent anglophone press bringing radical Palestinian voices to the world.

One of the things I love about VAGAGBONDS is the chance it offers for me to work closely with authors at every level: from the early development of concepts to the final wordsmithing. No one who has read Nick’s many books and articles would be surprised to learn about the clarity of his vision or his ability to write elegantly, efficiently, and in dialogue with the key thinkers of the moment. Still, I was impressed by how quickly and naturally this project came together, fueled by that sense of outraged urgency we all feel as we witness, daily, monstrous acts of horrific violence, infuriating cynicism and lies, and monumental political cowardice, all done in the name of Jews like us. This book was a cry against helplessness in the face of what will surely be remembered as a great historical turning point in the politics of our world.

Will there be critique “after” Gaza? (When will be “after”?) Much of what was comforting to believe about the role of the critical intellectual has been shaken. First and foremost, it has been shaken by the scholasticide in Gaza itself. Our colleagues have been slaughtered before our eyes. All the universities were reduced to rubble. Generations of research and knowledge have been obliterated. Beyond that, we are shaken by the attacks on critical scholars and students at universities around the world, notably in the US and Germany, two countries that claim the lineage of the Enlightenment and preen themselves on their academic reputation.

A faith in the project of critical knowledge production has also been shaken by the way that those countries and others have targeted campus pro-Palestinian activism to create a vicious spectacle of conspicuous repression, turning state violence against students and teachers into a gleeful rallying point of a politics of revenge. It has been shaken by the complacency and cowardice of the professoriate at so many universities, who have not only failed to speak up against genocide but have failed to lift a finger to defend their students (or, frankly, as is becoming more and more apparent, to defend themselves). It has been shaken by the fact that the situation many radical thinkers have been warning about for decades (genocide, fascism) is now here: our alarm was in vain. We lost.

The signature intellectual project of the “Western” social sciences and the humanities since the 1930s–to create a world that has truly learned from Nazism and the Holocaust–has evidently failed (as many knew it would, when they saw its silence on colonialism). The university is not merely in ruins, but, as Nick frames it, it is rubble: vicious fragments, pulverized dreams, the dead.

What comes next? There are politics of the streets, and, as Nick worked on the book, he was a stalwart supporter of the occupations at New York University, trying his best to support the students and junior colleagues being targeted by the police and administration. And yet this book and the VAGABONDS series is not content to say that there is no time for critical theorization of the present conjuncture. Indeed, as the world shifts and rubbles, we need it more than ever. But we need it in the form of insurgent, disobedient, risk-taking, and firmly committed thinking that To See in the Dark represents.

The book’s title invites us to the work: we must discover, together, new senses, new ways of seeing, new ways of associating, for times that do not offer any straightforward exit. Ultimately, To See in the Dark is an invitation to find resolve in the face of heartbreak, to strive for solidarity in the face of complexity, to recognize our common and uncommon agonies.

In some of the early advertising copy for VAGABONDS I somewhat romantically suggested the pamphlet-style short books should be found on the coffee table of comrades who fall into bed together after the march, tucked inconspicuously inside other books inside libraries and lecture halls, and displayed on the defamatory evidence table of a police press conference alongside Sharpie markers, vinegar-soaked bandanas, crimson lipstick, and the glass bottle with its ambiguous contents. I’m not sure we’re there yet, but it’s a worthy dream, and I’ve seen stacks of To See in the Dark at the registration tables of several teach-ins and Gaza fundraisers in London, Berlin, New York, and elsewhere.

What is the role of the radical book in the years to come? Only some of that question can be answered by what lies between the covers. We must, I suspect, also attend to how a book circulates as a physical and digital object. As it has ever been, the book is an alibi for weaving the fabric of our sociality and solidarity. A comrade lends you a dog-eared paperback. Someone you met on Instagram sends you a pirated PDF. A flirt buys you a book but makes you go to their favorite bookstore to pick it up. You learn of the book that will change your life because it has been banned or pulped. A book is, now more than ever, a talisman, a fetish into and onto which we project that which we hold sacred: that part of us that can still say “this world is unacceptable and some ‘we’ of which I I know I must be a part but which dares not speak its name is be on the horizon.”

Like all VAGABONDS books, this one contains a frontispiece illustrated by Amanda Priebe, inspired by a tarot card selected by VAGABONDS consulting witch Stella, based on the book’s themes and arguments. From the depths of the crackdown of pro-Palestinian activism in Berlin, Amanda provided us with an image that is now being used much more widely for posters, pamphlets, patches, and other media: fraying, loosely woven fabric (like a burial shroud, like a keffiyeh) parts to reveal, in the negative space, the outline of Palestine. A single lonely, steadfast candle, depleted but not defeated, burns in the center of the image, radiating light. Winged beings, perhaps birds, ascend. (Or do they descend?.) The image is not, to my mind, a hopeful one. Who, today, has the audacity and privilege and foolishness to demand hope? It is a testament to struggle, to refusal, to seeing in the dark.