I arrived in Ramallah well prepared . . . or so I thought.[1]I’m indebted to our delegation – Kehaulani Kauanui, Bill Mullen, Nikhil Singh, Neferti Tadiar; our organizers and hosts – Sunaina Maira, Magid Shihade, Rana Barakat, Lisa Taraki, Dunya Alwan, … Continue reading I’d read Saree Makdisi’s chilling portrait of Palestinian life under occupation, historical accounts by Rashid Khalidi, Walid Khalidi, Ilan Pappe, Nur Mashala, and Gabriel Piterberg, powerful critiques of Israeli apartheid leveled by Ali Abunimah, Omar Baghouti, and Uri Davis, exposés penned by Israeli journalists Amira Hass and Gideon Levy, as well as pro-Zionist voices such as Amos Oz and A.B. Yehoshua. I had Edward Said by my side, and the Electronic Intifada and the Palestine Monitor in my web browser. Our small delegation, formed at the behest of the U.S. Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel, consisted of some of the smartest people I know, their collective knowledge of the situation surpassed only by our hosts at Birzeit University in Ramallah. We were there on a fact-finding mission.

The checkpoints, the separation wall, the crumbling, half-constructed buildings, the fatigue-clad and heavily armed kids checking IDs, the freshly paved settler roads, the ever-expanding Jewish settlements rising from hilltops laying siege on Palestinian villages below–I’d seen it all before in books, articles, on Youtube, though now the “facts on the ground” were real, tangible, elbowing my heart, burning my eyes. We heard testimony from Palestinian families forced out of their homes in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem, saw Palestinian merchants in Hebron (or Al-Khalil) endure a daily barrage of bricks and garbage from ultra-Orthodox settlers intent on driving them out — a Palestinian city where nearly 2,000 IDF troops are deployed to protect about 500 Jewish settlers who terrorize the indigenous inhabitants with impunity.

I was prepared to gather “facts.” I was not prepared for Israel’s extraordinary efforts at normalization, and the Palestinians obstinate refusal to accept Israel’s projected image of itself as a “normal” modern democracy. It is a strange thing to cross the highly militarized zone dividing Ramallah from East Jerusalem, and minutes later stroll around Hebrew University’s Mount Scopus campus, with its state-of-the-art library and computer center, its lovely hilltop view, its Aroma Espresso Bar where students and faculty can read, chat, and simulate normal university life. The embattled Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood, a mere twenty-minutes by foot, feels like another country.

Walking from Sheikh Jarrah to the Old City, where tourists from around the world buy trinkets and take pictures oblivious to the realities of occupation, was strange enough. Seeing high-tech recycling bins scattered throughout Jerusalem was downright absurd. How ironic, I thought, for the state to promote a Green Israel while building a wall that forces Palestinians to radically extend their travel distance, destroys farms, and divides villages; to uproot Palestinian olive trees; to allow Israeli settlers in the West Bank to steal water for swimming pools while Palestinians must ration; to use chemical weapons such as white phosphorous against Palestinians.

But nothing prepared me for Jaffa Street. I had made a conscious decision to stay at the Palestinian-owned Jerusalem Hotel, just a few blocks from the Old City and around the corner from Salaheddin Street — the heart of the Palestinian commercial district. Except for perhaps the Educational Bookshop, a magnet for hip, keffiyeh-coifed Europeans and Americans, the local shops have seen better days. The area is run-down and heavily policed, and Palestinian youth treat the sidewalks as liberated territory to be held at all costs. Most everything closes after sundown, leaving huge strips of the district dark and desolate. One very cold night, I decided I’d had enough of the hotel restaurant and wandered past the Old City, past a line of cop cars streaming into the Arab Quarter, up the hill to a pristine, well-lit street paved with granite stone called Jaffa Street. I could not believe my eyes. It was as if I’d stumbled upon Rodeo Drive in Beverly Hills, or the Grove in Los Angeles. The street is teeming with shoppers and restaurant-goers, mainly Jews who live nearby and tourists, and the only vehicle allowed on Jaffa Road is the illegally built Jerusalem Light Rail system. It is both bizarre and grotesque to walk ten minutes from the dilapidated Arab quarter to the thriving, Jewish commercial center that is Jaffa Street. It is here, in the heart of Occupied East Jerusalem, where one can find Coffee Bean, Yogurtland, and a slew of high-end restaurants. For the first time during my two-week visit to the West Bank, I felt afraid. The surveillance cameras, the armed military personnel, the hundreds of people whose faces expressed either complete oblivion or utter contempt for Palestinians, not to mention the strange and hostile looks my solitary black self elicited — completely overwhelmed me. This is the face of normalization. It is not pretty.

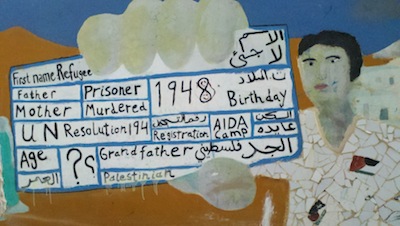

Israel’s normalization project works so long as Palestinians and their life conditions remain invisible, contained. But this is impossible, despite billions invested in security walls and barriers. Ironically, the greatest threat to Israel’s apartheid system that lay behind the wall is not the ugliness of violence, containment, and dispossession, but the beauty of struggle. Everywhere — in the refugee camps, at the universities, schools, and community centers, young Palestinian women, men, and children are waging a non-violent, creative movement to build a new, democratic, inclusive nation, free of occupation, free of second-class citizenship. I saw this most clearly at Aida Refugee Camp. Located between Bethlehem and the town of Beit Jala, the camp abuts the apartheid wall, which has cut off access to what had been Palestinian land. Thanks to the wall, children in Aida have no access to playgrounds or green spaces. Sandwiched between the opulent Jacir Palace Intercontinental Hotel, the notorious Bethlehem checkpoint, and the expanding Israeli settlement of Gilo, which occupies most of the area on the other side of the wall, Aida’s very presence disrupts Israel’s efforts to normalize this historic, commercially viable region. Overhanging the camp’s entrance is a giant key, a powerful symbol representing all of the homes lost in 1948, when Israeli forces drove some 700,000 Palestinians from their land. The story of al Nakba (the “catastrophe”) as it is known by Palestinians, is told in murals throughout the camp, depicting Israeli military invasion, the destruction of olive trees and suffering of displaced people, and, most importantly, the long history of resistance to occupation.

Mural at the Aida Refugee Camp in Bethlehem. Photograph by the author.

The Lajee Center and the Alrowwad Cultural and Theater Society, both based in the camp, exemplify the current cultural revolution. Founded in 2000 by eleven camp youths, the Lajee Center works with kids in the area of arts and media, including film, photography, and dance. Their youth photography workshop has mounted dozens of international exhibitions and published at least four books of photos and drawings depicting life inside the camp, the rediscovery of lands and histories lost during al Nakba, and children’s imaginative stories of overcoming the apartheid wall.

The Alrowwad Cultural and Theater Society, created in 1998, is a genuine community center, offering computer training, a library, photography and video editing, music and visual art education, women’s sewing and embroidery groups, and a gym for residents of all ages. But Alrowwad’s core project is its youth theater. Founding director, poet, playwright, and educator Dr. Abdelfattah Abusrour sees theater as a particularly effective means of expression for Palestinian youth, “a beautiful non-violent way of saying we are human beings, we are not born with genes of hatred and violence, we do not conform to the stereotype of Palestinians only capable of throwing stones or burning tires.” Himself born and raised in the Aida refugee camp, Abusrour knows occupation first-hand, having lived through the 1967 war as a four-year-old child. He took refuge in scholarship, earning a doctorate in biological and medical engineering, but then gave up a promising career in science for his main passion: poetry and theater. He returned to Aida Camp and has devoted his life to creating a “beautiful theater of resistance,” unleashing the creative capacity of young people to tell their story and realize a different, non-violent path to freedom. He is not interested in building Palestinian-Israeli dialogue or other such liberal projects that ultimately contribute to Israel’s normalization. His plays, such as “The Village Close By,” “Blame the Wolf,” and most recently “Handala,” based on the character created by the martyred Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali, explore histories of Palestinian resistance without sugar-coating the ugliness of occupation.

Alrowwad’s best known production, “We Are Children of the Camp,” is something of a collaborative venture, incorporating the kids’ own stories into a sweeping narrative about Palestine since 1948. The children speak from personal experience about Israeli soldiers invading the camps, shooting parents and then denying them access to hospitals on the other side of the wall. They long for human rights, a clean environment, freedom, a right to return to their land, and the right to know and own their history. They encapsulate this history in the play’s title song, in which they sing of being made refugees in their own land, colonies built, and villages demolished. “They put us in labyrinths,” they sang, “They planted hatred in us / They considered us as insects.” And yet, the children on stage, like their brothers and sisters and friends whom I met laughing, riding their battered bikes along the narrow camp streets, kicking around a scraped-up soccer ball, or querying me with questions about America, refused to become insects to be stamped out or cauldrons of hatred. “We may have a spring,” the song continues. “Sun may rise again in our sky / We look to Jerusalem / Singing for freedom in our hearts.”

Seeing first-hand the joy and confidence expressed by the children at the Aida Camp, the general sense of hope tempered by discipline, it occurred to me that what the Lajee Center and Alrowwad are doing is nothing less than nourishing a Palestinian renaissance and prefiguring a diverse, democratic, post-Zionist society. This is why normalization will never succeed. To invoke yet another song from the Alrowwad Children’s Theater, “1948”: “Occupation never lasts . . . The government of injustice, vanishes with revolution.” As more and more young Palestinians create a democratic alternative to settler colonialism and its racist, anti-democratic ideology, and more people around the globe join the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement and refuse to invest in Israel’s regime of occupation and apartheid, the “government of injustice” will indeed vanish. And something beautiful will take its place.

Top image: Mural at the Aida Refugee Camp in Bethlehem. Photograph by the author.

References

| ↑1 | I’m indebted to our delegation – Kehaulani Kauanui, Bill Mullen, Nikhil Singh, Neferti Tadiar; our organizers and hosts – Sunaina Maira, Magid Shihade, Rana Barakat, Lisa Taraki, Dunya Alwan, colleagues associated with Muwatin: The Palestinian Institute for the Study of Democracy in Ramallah, as well as Mada al-Carmel: The Arab Center for Applied Social Research, directed by Nadim Rouhana, and to my UCLA colleagues, David Myers and Gabi Piterberg for their critical insights and advice. I’m especially grateful to Gabi for suggesting the title. |

|---|